Thoughts on West Virginia's AI Guidance

Related: North Carolina’s Guidance review, free Humanity Amplified report.

Earlier last week, West Virginia released their AI guidance for schools.

Since I’ve read and studied all the other guidance reports that have been released (nationally and internationally), I thought I’d review this one as well. I hope all of these reports and the different feedback that people have provided on them contribute to a positive discussion aimed at both celebrating and strengthening all the guidance that is being issued.

I did add coverage of West Virginia’s guidance to the free Humanity Amplified report.

These are the 11 things that stand out to me in this guidance.

(1) Talking with students about AI

I don’t know that this is the only report where this is covered, but I like how this is said so directly, and I’m surprised there hasn’t been more buzz about this in education. AI is going to significantly impact the job market and will likely cause severe unemployment over the next few years. This isn’t debatable. Optimists focus on the time society has to adapt and human ingenuity that drives people, leading to new jobs and individual businesses over time, but no one is saying there won’t be significant challenges to employment in many areas, including, most significantly, the areas we are training our students for — knowledge work — in the short term. “Short-term” (decades-long) unemployment that was triggered at the beginning of the first industrial revolution was brutal, and this is expected to be no different.

I also think it is important to cover other areas where AI is going to be disrupted: education and health care (predictions are those will be the two most disrupted sectors); energy; deep fakes; governance/democracy; representation/bias; and generally, what it might be like to live in a world where machines are millions of times smarter than people, a world all of our students will live in.

Students should start thinking about future jobs, what types of skills they will need to develop, and even what universities they want to attend, as some are way more prepared for this than others.

(2) AI writing/”plagiarism” detectors

Yes, these tools are not reliable, and it is wonderful to see a state take such a strong stance against the tools.

(3) Updates

Statements such as these are common in guidance documents, and I frequently hear educators discuss how difficult it is to keep up with the changes.

If you view the changes as individual changes rather than part of a continuum across many lines, I agree that this can be difficult. But if you view them as part of a trend across some lines, I think it’s much easier.

To highlight this, let’s review the AI explainer, which I think is a bit confusing, to be honest, but it can be used to highlight where things are going.

I think this AI explainer is a bit confusing because it sort of conflates generative AI (GAI) with all artificial intelligence (AI). The header does it explicitly, and so does the explanation. The confusion is compounded by the next page of the document that identifies the limitations of AI in the context of GAI, but those limitations do not necessarily apply to all AI.

Let me explain.

Generative AI (GAI) generates text, voice, images, and video (combining these creates “multimodal” generation) in ways that are later described in the WV report. But GAI cannot problem-solve or plan. It could potentially, I guess, perceive data, but it cannot yet perceive a situation and make decisions or problem-solve and plan. This is well-established and agreed upon in AI.

AI (not GAI) can make predictions, but it’s not really autonomous enough yet to make its own decisions. Whether or not it “understands” what it is doing is highly debatable, but even those who think it can understand put such understanding at very minimal levels.

This said, I think it’s more of a matter of clarifying here than being wrong about what educators need to think about. AI scientists are developing AI models that can reason and plan. This was part of the blow-up about OpenAI’s potential “ProjectQ,” which I explain in detail here. Regardless of whether or not “ProjectQ” is at OpenAI is a real thing, OpenAI is certainly working on AIs that can reason and plan, and it is likely that we will soon see AIs that can reason (most, though not all, including some very accomplished ones, think that AIs can engage in basic inference reasoning but cannot engage in abstract reasoning) and plan. When AIs can significantly reason, plan, and problem-solve (either through LLMs or other models), they will be able to do a lot of what we can do at work in general and in school in particular. In this world, AI won’t be limited to making “algorithmic guesses.”

This description applies to generative AI, not all AI, including the broader definition of AI that is included under the “Generative” subheading. This is a full-blown world of autonomous agents that can reason and plan from what they “see,” not text predictors.

My point in clarifying this is to point out that the changes that are coming are predictable. Educators should be reacting to each change and updating their reports; they should be planning ahead for what is here/coming.

What is that? AIs that can

*Produce text, voice, image, video, and a combination of all of those (multi-model) in hundreds of languages

*Read, listen, see (image and video), and do all of those at the same time (multi-model) in hundreds of languages

*Simulate human emotions and connections

”Simulate human knowledge capacity

*Reason

*Plan

*Problem-solve (reason + planning)

*Predict (can do now)

*Discover

*Have common sense

*Have empathy

Those are here/on the way. Once AIs can do them all, then they can do what humans do. And they’ll be able to do it more reliably at a fraction of the price. I could go on (you should read our report), but you get the point.

Schools need to prepare for a world where AI can do all of these things and look beyond generative AI and text prediction. In practice, that means we have AIs that can do more than write; it means we have AIs that can now translate languages in real-time conversation (already here [Meta; Timekettle]), assess students, and develop student-specific instructional plans, actively teach content to students, eliminate the need for testing because AIs already know what students know as they work with them, appear in XR environments, and appear as holograms. These AIs essentially become autonomous (in the form of “agents”), intelligent humans that exist in computers (laptops, XR glasses, holograms), silicon, and synthetic biological systems.

It is essential that schools start to consider their value propositions in a world where machines are capable of all of the above and are competitive with humans in all domains in which humans are intelligent.

Some may consider this a bit of “hype,” but remember that many AI scientists didn’t think AI would ever be able to capture the nuances of human language, something it is already doing and getting better at each day. And even if it is farther off (say, 3-5 years), it will take many schools 1-2 years to get PD programs scaled and implemented in schools. The reality is that we could have AGI based on limited definitions before all teachers have a good understanding of AI. And even if we don’t ever get to AGI, AIs will still have substantial enough capabilities to significantly disrupt education.

As Sam Altman noted on a recent podcast with Bill Gates:

I think it’s worth always putting it in the context of this technology that, at least for the next five or ten years, will be on a very steep improvement curve. These are the stupidest the models will ever be. Coding is probably the single area from a productivity gain we’re most excited about today. It’s massively deployed and at scaled usage at this point. Healthcare and education are two things that are coming up that curve that we’re very excited about too… It’s not that we have to adapt. It’s not that humanity is not super-adaptable. We’ve been through these massive technological shifts, and a massive percentage of the jobs that people do can change over a couple of generations, and over a couple of generations, we seem to absorb that just fine. We’ve seen that with the great technological revolutions of the past. Each technological revolution has gotten faster, and this will be the fastest by far. That’s the part that I find potentially a little scary, is the speed with which society is going to have to adapt, and that the labor market will change.

- Sam Altman, CEO, OpenAI

To pull this into the practical, Donald Clarke recently (1/14) posted:

Seems interesting, but what do we think of the Kim Kardashian tutor?

Is Taylor Swift next? How can teachers “compete” with that? Could a teacher compete with “Learning Math through Football” with Taylor Swift and Travis Kelcie?

(4) Human-in-the-loop

All of the guidance documents make a strong case for “humans in the loop,” which is generally interpreted to mean humans get the final say. This is a good principle to live by, as education is about humans, but as I explained in the review of NC’s guidance, there are things AIs will be able to do better than us, such as provide greater consistency and fairness in assessment and placement (IEPs, APs, etc.) across a school, district, or state. When that happens, it will be difficult for schools to justify having a human override the assessment and, perhaps, placement recommendation made by the AI. If they do, lawsuits may follow.

(5) Guiding Principles

Since the first time I read the WV report, I was excited about this inclusion. I think that each of the statements has merit, but, more significantly, I think it helps all educators think through how and why AIs are being used in the classroom. Something similar to this could be drafted on an individual school or district basis.

(6) Developing humans

Many believe that existing AIs are creative, and as they develop problem-solving and planning abilities, they will be capable of critical thinking. But even if AIs develop those capabilities, we still need to develop people who can think, be creative, and offer their own insights. On the job, we certainly do not say we don’t need to think or be creative because our coworkers are capable of doing these things. Regardless of how capable machines become, we still need to develop human capacities to interact with each other and AIs. In our report, we outline in detail how to actualize that.

(7) AI Citations

The guidance takes a strong position related to documenting any use of GAI output in schoolwork. Conceptually, this makes sense, but it is worth nothing that GAI tools are now embedded in most products students and teachers use, including the Google and Microsoft suites, search engines, Canva, SnapChat, etc.

Given how integrated GAI is into the workflow, citing every instance becomes a practical challenge, as it wouldn’t make sense to highlight sentences or parts of sentences within a document and cite all the different tools that may have been used to aid in the development of those individual sentences.

The “How to Cite” generative AI documents from MLA, APA, and Chicago came out in the spring of 2023, when GAI was more novel, accessible in only a few places (ChatGPT, for example), and GAI was being used to produce entire articles and school papers. In this case, I think it makes sense to cite it (“I wrote this paper (almost) entirely with ChatGPT” (I’m not sure a student would do that)), but citing every instance of generative AI usage when it is simply integrated as part of a workflow is probably not practical.

That said, I think it makes sense to cite GAI in a few instances.

(1) If a teacher is trying to work with a student to teach him or her how to use GAI, having them articulate exactly how they used it is important.

(2) If a student is relying on GAI output for a factual claim (I would never recommend this, as these systems cannot be relied on for factual information (though they are getting much better in this regard)).

(3) If a substantial portion of work or text is generated from it (perhaps a paragraph or more).

(8) New assignments and assessments

At a broader level, the goal is to design new assessments that cannot be easily completed with AI (especially since, as the report notes, the AI writing detectors are not reliable) and can help students develop skills needed for an AI world, at least in whole. As noted, teachers can use AI to help them do this. This will largely require a shift in classroom instruction toward oral presentations with questioning, classroom debates, project-based learning, and experiential learning. Adapting education to the AI world will require a significant shift in contemporary educational practice, and PD should include that.

(7) Professional development. Teachers who do not understand the technology cannot write classroom policies for AI usage, cannot help build assignments based on such policies, and cannot react to guidance such as the ones being issued without such training.

According to a recent survey, only “82% of college professors are aware of ChatGPT, compared to only 55% of K–12 teachers.” [And this is just ChatGPT!] For this technology to be utilized in schools, teachers must understand it.

(9) AI Literacy

I’ve been writing extensively about AI literacy since last spring, and regardless of one’s perspective on integrating AI usage into the classroom, I think it’s essential that students learn about the world they are starting to live in.

There are a few notes related to that that this report brings to mind.

First, I think it is essential that this extends beyond the students to the entire school and into the broader community. At a minimum, parents need to understand how it is being used in schools.

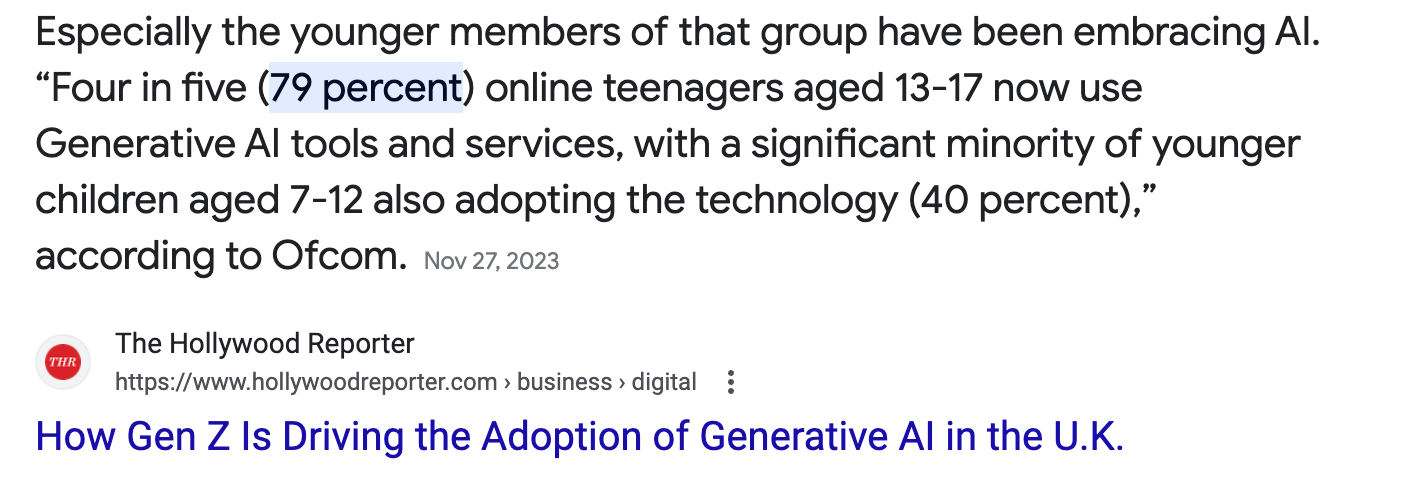

Second, parents also need to understand how AI, and generative AI in particular, is being used by their children at home. As noted in the report, it is difficult to find GAI systems that allow use by students under 13, which makes it difficult for students to permit use of the technology, but there are no age verification systems on these tools, and students below this age range use it at home.

In a survey of students in the UK, 40% of students ages 7-12 are using it.

Similar percentages are likely in the US. This creates complications in providing appropriate instruction to students who are already using it, for teachers to manage expectations related to classroom assignments, and for assessment expectations (students using it are generally going to be able to do better work than those who are not using it.

This is aggravated by some parents teaching their children how to use these tools, giving an advantage to those whose parents are able to do so.

A core function of public education has always been to close the gap between the more privileged and the less privileged. Schools can only help with that if this 13+ issue can be tackled.

Moreover, if parents are being asked to sign “AI consent” forms, they need an understanding of AI.

Third, I think it is important to expand AI literacy beyond an emphasis on computer science.

As noted at the beginning of the WV report, AI is going to significantly impact the job market. AI is also going to significantly impact the distribution of wealth, politics, energy consumption, global power projection, warfare, and how we relate to each other (the second most popular “AI” site after ChatGPT is character.ai, where people interact with AI characters for an average of 2 hours per day). AI will have consequences at least as big as electricity and will likely require a restructuring of the educational system. All of this needs to be incorporated into AI literacy. I encourage you to examine the details in our report.

(10) Existing laws. One thing the report does exceptionally well is reference existing laws that apply to AI in school. Other state reports have made some references to similar laws and related state-based resources. Generative and other forms of AI is technologies that are going to impact every form of assessment and all operations of a school, so there are many other relevant laws and resources.

(11) The report does hit the major concerns (overreliance, reduced social interactions, safety issues, the digital divide (which only schools can fix…, “cheating”), and the benefits (operational efficiency, assessment, differentiation, tutoring, collaboration, and security).

Conclusion

The WV report ends by listing its goals, and, as it rightly acknowledges, AI is going to materially impact every single one of these goals. There is never a better time to get started with AI literacy and prepare students, teachers, administrators, and staff for an AI World.

This report makes a substantial contribution to that effort. It identifies the significance of discussing the emerging labor markets with students, setting classroom expectations for instruction and assessment that do not rely on writing detectors, and the importance of AI literacy for students, teachers, administrators, staff, and the larger community.

As AI continues to advance over the very near term, it will present considerable challenges to the limitations of AI identified in the report, making it more difficult for users to cite all instances of AI usage, find unique human capacities (“machines can never do ‘x’), keep humans in the loop, compete with AI tutors, and tackle how to integrate autonomous AI agents in the form of teachers and tutors into the education system while simultaneously reconfiguring instruction so students can succeed in an AI world. Guidance that includes awareness of those evolving capabilities and the likely significance of needed changes. will also help schools. Updates will be needed to tackle these questions.