Where Is Education Heading?

Key Takeaways

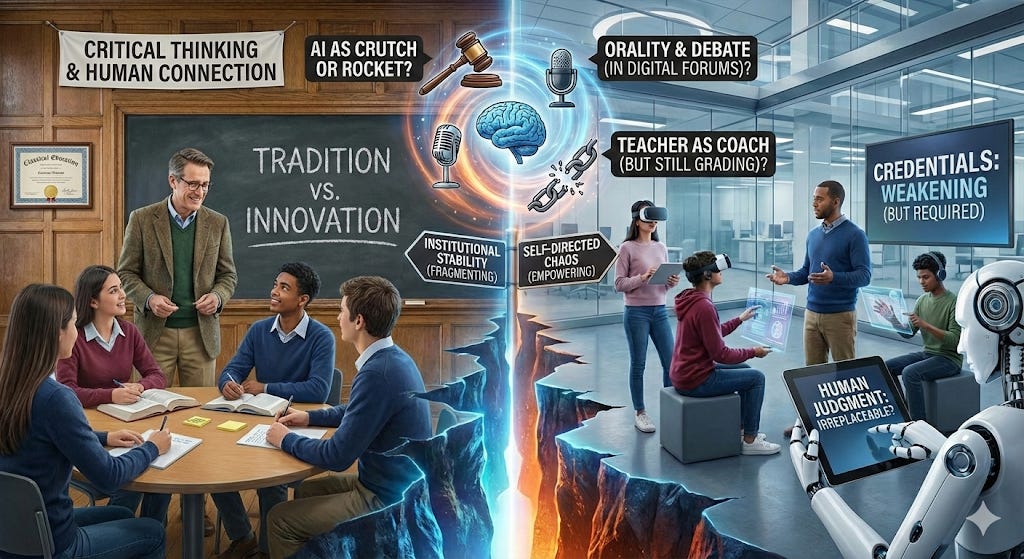

Education will split, not converge. Credentials will weaken before curricula change. Teachers will shift from explaining to coaching—whether they like it or not. Technology will force value choices, and schools will pick sides. Orality and judgment will become the new proof of learning. The gap between where education is heading and where it should head is, in many ways, the whole problem.

Introduction

Someone asked me last week where I think education is heading. I answered on the spot, and in retrospect my response blurred together two different questions: where I think education is heading and where I think it should head. These are not the same.

It’s an important question, so I want to answer it more thoroughly here. No one has the full picture, but the direction of travel is clear.

Before I get into projections, however, there are a couple of important notes.

Two Categories of Learning

There are really two basic categories of education we need to distinguish:

(a) Institutional learning—what happens in schools, from kindergarten through graduate programs. This is what most people picture when they hear “education”: classrooms, teachers, curricula, grades, diplomas.

(b) Self-directed learning—everything else. Learning from family. From YouTube tutorials. From TikTok explainers. From online courses. From tutors. From AI chatbots. From simply doing things and figuring them out.

Within institutional education, there’s enormous variation—public and private schools, K-12 and universities, professional schools and vocational programs. It’s hard to think carefully about all of them at once. Most of my work has been in K-12, so that’s where I’ll focus, though much of what I say applies more broadly.

Here’s the uncomfortable reality: self-directed learning is growing rapidly and, for many students—particularly in upper grades—may have already become an important source of meaningful learning. The question isn’t whether this trend will continue. It’s how institutions will respond to a world where some version of a teacher is in every student’s pocket, available after school and on weekends.

What I see emerging can be understood through four forces that will reshape education over the coming decade.

Force 1: Exponential Capability vs. Slow Institutions

The first force is a collision: AI capability is expanding exponentially while institutional decision-making operates on linear timescales.

Most Institutions Will Not Respond as They Need To

Schools will fail to adapt at the pace and scale required. This isn’t because educators don’t care—most care deeply. It’s structural.

First, there’s a profound comprehension gap. Many administrators and school board members genuinely don’t understand what AI can do today, let alone what it will do in two years. Parent awareness is equally low. Often, when I show educators what today’s AI can produce—not just essays, but code, analysis, creative work, and multi-step, iterative problem-solving—many are genuinely shocked. They’re still operating on assumptions from 2024, or even 2023.

Second, there’s institutional disbelief. It’s psychologically difficult to accept that the core model of education you’ve built your career around might be undermined by intelligence in a computer. Denial is easier than reckoning.

Third, and most importantly, institutional timelines can’t match the pace of change. A curriculum revision takes 1-2+ years. A new teacher training initiative takes longer. By the time schools implement their response to GPT-4 (yes, models are already past that), we’ll be dealing with capabilities several generations beyond it. Schools are playing catch-up to a target that’s accelerating away from them. And since they are frequently in disbelief, they don’t want to plan for what is coming.

Most Teachers Will Not Fundamentally Adapt

This is not a criticism of teachers. It’s a critique of a system that has, over decades, optimized for a particular kind of educator—and actively punishes those who deviate.

The current system rewards teachers who are comfortable with standardized curricula and standardized testing. But it goes further than mere rewards: teachers who try to innovate face real consequences. Deviate from the pacing guide and you’ll hear about it from administration. Experiment with assessment methods that don’t align with state tests and your students’ scores—and your evaluation—will suffer. Spend time on skills that matter but aren’t measured and you’ll fall behind on content that is. The bureaucratic environment doesn’t just fail to support creativity; it actively punishes it.

Teachers who prefer more creative approaches, who want control over what and how they teach, who chafe against scripted lessons and test-prep mandates—many of them left. They burned out, moved to private schools with more autonomy, or exited education entirely. The teachers who remain are, on average, those for whom the current model works reasonably well. This isn’t a character flaw; it’s a rational response to incentives.

Transforming education requires transforming what happens in every classroom. Every teacher, across every subject, would need to rethink not just their assignments but their entire approach to teaching. Schools will need to rethink the subjects themselves—at least the relative importance of many. This is vanishingly unlikely to happen at scale.

Teachers are overworked, underpaid, and operating within systems that provide little support for genuine pedagogical experimentation. Most entered the profession because they found meaning in a particular mode of teaching—direct instruction, seminar discussion, writing—and asking them to abandon what works for them is asking a great deal. Professional development is inadequate for a challenge of this magnitude.

Some teachers who love change will adapt brilliantly. They already are. But systemic change requires changing what typical teachers do, not just what exceptional ones do.

Change Will Happen Where There Is Leadership

Educational leadership today is often largely managerial. Principals and superintendents are trained to optimize existing systems: improve test scores incrementally, manage budgets, navigate compliance requirements, keep parents reasonably satisfied, avoid controversy. These are valuable skills for maintaining stability. They are inadequate for navigating disruption.

What’s needed now is transformational leadership—leaders willing to question fundamental assumptions about what school is for and how it should operate. This means leaders who can articulate a vision for education in an AI-transformed world, even when that vision is necessarily uncertain and evolving. It means leaders who can build coalitions among skeptical teachers, anxious parents, and cautious school boards. It means leaders willing to take risks, to pilot radical experiments, to fail visibly and learn publicly.

This kind of leadership is rare in any field. It’s especially rare in education, where the consequences of failure fall on children and where institutional cultures prize stability over experimentation. The incentive structures work against it: superintendents who rock the boat get pushed out; principals who deviate from district mandates face consequences; school board members who propose dramatic changes lose elections.

The leaders who will matter most in the coming decade are those who can navigate this tension—who can maintain enough institutional legitimacy to keep their jobs while pushing hard enough to actually change things. They will need to be translators, helping communities understand why transformation is necessary. They will need to be protectors, creating space for teachers to experiment without fear. And they will need to be learners themselves, humble enough to admit they don’t have all the answers in a landscape that’s shifting beneath everyone’s feet.

Some of these leaders exist.

Force 2: The Fragmentation of Models and Credentials

The second force is fragmentation. As traditional schools struggle, the broader educational ecosystem will multiply and diversify.

The System Will Diversify

People sense—even if they can’t articulate why—that the status quo is insufficient.

Homeschooling is expanding, driven partly by pandemic disruption but sustained by something deeper: a growing skepticism about what schools actually deliver. Charter schools continue to proliferate. School choice programs are making private options accessible to more families. Online schools are gaining legitimacy. And innovative models like Alpha School are experimenting with radically different approaches to what school even means.

This diversification is, on balance, good. We’re entering a period that requires experimentation. We genuinely don’t know what educational models will prove most effective in a world where AI can outperform most students—and perhaps most professionals—on most traditional knowledge-work tasks. The only way to find out is to try many approaches and see what works. Everything, even the continuation of the status quo, is an experiment. Monocultures are fragile; diversity creates resilience.

Education Risks Becoming a Closed Loop

Here’s a troubling possibility: education will increasingly become a self-referential system, optimizing for its own internal metrics while losing connection to the broader world it supposedly prepares students for.

Schools will teach what schools can assess. They’ll assess what schools can teach. The curriculum will be justified by its relationship to further schooling (this prepares you for high school, which prepares you for college, which prepares you for...). The entire system will operate as a closed loop, with diminishing reference to what students actually need to thrive in a world being transformed by AI.

The glue holding this closed loop together is credentialing. Parents don’t stay in the system because they necessarily believe in the learning—many have serious doubts. They stay because they want the diploma, which serves as a gatekeeper for the next loop: high school diploma to get into college, college degree to get a job, graduate degree to advance. The credential matters more than the competence it supposedly represents. Everyone knows this; few say it aloud.

This is why the diversification I mentioned earlier matters so much. As alternative credentials gain legitimacy—industry certifications, portfolio-based assessments, demonstrated skills rather than seat time—the monopoly of the traditional degree will weaken. Not disappear, but weaken. When employers start hiring based on what candidates can actually do rather than where they went to school, the closed loop begins to crack. We’re not there yet, but the pressure is building.

The gap between what schools reward and what the economy values is widening. Students who optimize for school success may be optimizing for the wrong things.

Technology Will Divide Schools

Every new technology will present schools with choices that divide them, and these divisions will compound over time.

We’re already seeing it with phones. Some schools ban them entirely; others allow them; others try various compromises. There’s no consensus, and the debate is fierce. Laptops are next—the push to remove them from classrooms is gaining momentum. AI-specific tools are already contentious.

But here’s what most educators haven’t grasped yet: the interface of education is about to fundamentally shift. We’re moving from screens on desks to information layered over reality itself.

Coming soon: AI glasses (likely 2026-2027) that overlay information on the world. A student wearing these could have real-time translations, instant definitions, historical context about whatever they’re looking at, step-by-step guidance for any task—all without anyone knowing they’re accessing it. This isn’t science fiction; the technology exists and is rapidly improving. Eventually: brain-computer interfaces that further blur the line between what’s “you” and what’s “technology.”

When information access becomes invisible and ambient rather than visible and device-based, the entire framework for thinking about “technology in the classroom” collapses. You can confiscate a phone. It’s hard to confiscate glasses that look like regular eyewear. AI pins? AI pens? Contact lenses with AI models? You certainly can’t confiscate a neural interface.

The fundamental question will be: how “AI-enabled” will schools permit students to be? Schools that restrict technology will brand themselves as protecting “authentic” learning. Schools that embrace it will position themselves as preparing students for the real world. Parents will face genuine choices about what kind of education they want for their children. There is no neutral position here.

Force 3: Human Value Shifts—From Content to Judgment and Dialogue

The third force is a fundamental shift in what education should optimize for. If AI can handle information transmission better than any teacher, what’s left for schools?

What Success Should Mean in an AI Era

Before examining how schools might change, we need to define what education should optimize for when machines can do most of the cognitive work we used to train students to perform. Most schooling still optimizes for recall plus compliance. That’s the wrong target.

In an AI-transformed world, education should develop:

Judgment under uncertainty—the ability to make decisions when data is incomplete, stakes are high, and algorithms disagree

Taste and discernment—knowing what’s good, what’s worth pursuing, what questions are worth asking

Ethical reasoning—navigating moral complexity when easy answers don’t exist

Collaboration and leadership—working with others toward shared goals, including AI systems

Agency and self-directed learning—the capacity to identify what you need to know and figure out how to learn it

Communication in real time—speaking, listening, persuading, and responding when you can’t edit your words

These capabilities share a common thread: they require human presence and judgment in ways that can’t be outsourced or automated. They are also, notably, not what most schools measure.

Many Schools Will Circle the Wagons Around “Human Connection”

Watch for an emerging “ed tech lash”—a backlash against technology in schools that will intensify even as the technology becomes more powerful.

Some of this is justified. Schools rushed to deploy laptops and tablets without thinking carefully about how to use them productively. Many classrooms became places where students stare at screens doing digital worksheets that are no better—and often worse—than paper ones. The research on phones in schools, at least when overused and when it is assumed that traditional schooling is the primary route of knowledge transmission, is genuinely concerning. Critics have legitimate grievances.

Schools will increasingly emphasize “human-to-human learning” and “authentic relationships” as their distinctive value proposition—even in cases where students might actually learn better from AI tutors. We’ll hear arguments about how students need human connection, how they crave it, how nothing can replace it. People will say this even if the students say they’d rather learn from an engaging and gamified adaptive learning system and the research shows students learn more and faster that way.

My point is not that technology will necessarily be more effective at teaching content than humans, but that many schools will insist on human instruction even if research proves otherwise. And many schools will cite evidence about pandemic learning in “Zoom” rooms and untrained students using iPads to contradict potential research about the benefits of gamified adaptive learning systems.

Of course, even if AI is better at some kinds of instruction, schools still matter for belonging, identity, norms, and social development. But the question should be how to actualize these regardless of how content instruction is best delivered.

Schools With Industry Ties Will Have Advantages

As the gap widens between what schools teach and what students need, institutions with strong connections to actual workplaces will have significant advantages.

Internships will become more important—not as résumé items but as genuine learning experiences. Students who spend time in real work environments will understand, viscerally, what skills matter and how AI is actually being used. Schools can’t teach this; they can only facilitate access to it.

Universities with strong industry partnerships will be better positioned to keep curricula relevant. High schools with robust work-based learning programs will produce graduates who understand what awaits them. Schools that remain sealed off from the economic world will increasingly train students for a reality that no longer exists.

Over Time, Successful Models Will Be More Deweyan

The educational thinkers who will prove most relevant aren’t the technologists but the pragmatists—particularly John Dewey.

Dewey argued, a century ago, that education shouldn’t be preparation for some future life but rather should be life itself. Students learn by doing, by engaging with real problems, by participating in communities that matter. Knowledge isn’t something transmitted from teacher to student; it’s something constructed through experience and reflection.

This vision fell out of favor as schools industrialized, standardized, and focused on scalable knowledge transmission. But in an AI age, Dewey’s critique is more relevant than ever. If AI can handle information transmission better than any teacher, what’s left for schools? What Dewey always said: creating environments where students grapple with genuine problems, collaborate with others, develop judgment through experience, and learn to think—not just know.

The schools that thrive will be those that stop trying to compete with AI at information delivery and instead focus on what Dewey called “learning by doing”—experiential, collaborative, and rooted in real-world engagement.

Teachers Will Eventually Become Coaches

Here’s what the teacher role will likely evolve toward—for those who remain in the profession and adapt successfully.

The traditional model casts the teacher as content expert and information transmitter: the sage on the stage who lectures, explains, demonstrates, and evaluates. This model made sense when teachers were the primary gateway to knowledge. It makes less sense when an AI tutor can explain any concept, at any level, with infinite patience, available 24/7, and increasingly personalized to each student’s learning style and pace.

What AI can’t do—at least not yet—is care whether a student shows up. It can’t notice when a teenager is withdrawn because of trouble at home. It can’t inspire a reluctant learner to push through frustration. It can’t model what it looks like to be a curious, engaged adult who finds meaning in learning. It can’t build the kind of relationship that makes a student want to become their best self.

The emerging model recasts teachers as coaches, mentors, and motivators. Adaptive learning management systems will handle much of the content instruction—identifying gaps in understanding, providing targeted practice, adjusting difficulty in real time, tracking progress across skills. Teachers will guide students through this landscape: setting goals, monitoring engagement, intervening when students struggle emotionally or motivationally, facilitating collaboration, and helping students make meaning of what they’re learning.

This is a profound shift in professional identity. Many teachers entered the profession because they love their subject and want to share that love through instruction. Asking them to step back from direct teaching and become learning coaches is asking them to become different professionals. Some will embrace it; many will resist or struggle. The transition will be messy.

But for students, this model may be superior. They get the best of both worlds: AI-powered instruction that adapts to their individual needs, combined with human relationships that provide motivation, accountability, and emotional support. The teacher’s value shifts from what they know to who they are and how they connect.

Orality Will Rise

Here’s a trend I see as genuinely hopeful: orality—spoken communication, dialogue, real-time thinking—will become more important in education.

When AI can produce polished written work on demand, the ability to write an essay becomes less distinctive. But AI can’t (yet) participate in a live Socratic dialogue. It can’t debate in real time with the give-and-take of human exchange. It can’t demonstrate, under pressure, whether a person actually understands what they claim to understand.

Classroom debates, oral examinations, Socratic seminars—these ancient educational forms are suddenly relevant again. They test what AI cannot fake: the ability to think on your feet, to respond to unexpected challenges, to demonstrate genuine understanding through dialogue.

I’ve spent forty years in debate education. I’ve watched it develop skills—critical thinking, evidence evaluation, perspective-taking, real-time argumentation—that prepare students for exactly the world we’re entering. The schools that invest in orality, in dialogue, in forms of learning that require human presence and real-time engagement, will produce graduates who can do things AI cannot. That’s where the human advantage lies.

Force 4: A Widening Gap—AI as Rocket Ship or Crutch

The fourth force is perhaps the most consequential: AI will dramatically widen the gap between students who use it to accelerate their learning and those who use it to avoid learning altogether.

Some High School Students Will Out-Earn Their Teachers

This sounds provocative, but it’s already beginning. AI dramatically lowers the barriers to starting businesses, creating content, and monetizing skills. A teenager with entrepreneurial instincts and AI fluency can now accomplish things that previously required teams of professionals.

High school students are often more adept with new technologies than adults. They’re digital natives raised on rapid iteration. Some will leverage AI to build businesses, create products, or offer services that generate significant income—more than the $50,000-90,000 their teachers earn.

This will create awkward dynamics in schools. What authority does an institution have over a student who’s demonstrably succeeding by metrics the institution claims to value? How do you motivate traditional academic work when some students have discovered they don’t need it? Schools will struggle to maintain relevance when their most capable students have routes to success that don’t pass through the classroom.

AI as Rocket Ship or Crutch

Some students will use AI as an educational rocket ship—a tool that accelerates their learning, exposes them to more sophisticated material, provides instant feedback, and helps them reach levels of achievement previously impossible. These students will soar.

Other students will use AI as a crutch—a way to avoid thinking, to complete assignments without learning, to perform competence they don’t possess. These students will fall behind in ways that may not be immediately visible but will become devastating as they advance.

Schools, for the most part, will fail to distinguish between these two uses. The same tool can be rocket ship or crutch depending on how it’s used, and schools lack the capacity to monitor and guide usage at scale. Without substantial curriculum redesign—making assignments that can’t simply be outsourced to AI—the gap between these two groups will widen.

This is perhaps the most urgent challenge: not whether students use AI, but how. Most current assignments can be completed entirely by AI. Until that changes, schools will be sorting students by who uses AI well versus who uses it poorly, while pretending the sorting is about something else entirely.

What This Means for Parents

If you’re a parent navigating these changes, here are five questions to ask any school:

How do you assess real understanding now that AI can write? If the answer involves only written assignments, keep pushing. What oral assessments, demonstrations, or real-time problem-solving do students do?

What do students do here that is hard to outsource to AI? Look for dialogue, collaboration, physical making, real-world projects. Be skeptical of schools that can’t answer this clearly.

How do you teach students to use AI well instead of hiding it? Schools that ban AI entirely are training students for a world that won’t exist. Schools that ignore it are allowing crutch behavior. The best schools are teaching discernment.

Where do students practice speaking, argument, and dialogue weekly? If the answer is “English class discussions sometimes,” that’s not enough. Debate, Socratic seminars, oral presentations, and real-time collaboration should be central, not peripheral.

What real-world work, internships, or projects exist? Students need exposure to how work actually happens now, not how it happened twenty years ago. Schools with industry connections will deliver better preparation.

These questions won’t give you certainty, but they’ll reveal which schools are thinking seriously about the future and which are hoping the future doesn’t arrive.

These questions won’t give you certainty, but they’ll reveal which schools are thinking seriously about the future and which are hoping the future doesn’t arrive.

A word of caution: these questions should open dialogue, not shut it down.

The goal isn’t to catch administrators off guard or create an adversarial moment. Most educators are doing their best within systems that constrain them. They’re often as anxious about these changes as parents are—and frequently more informed about the practical obstacles to change. The conversation you want is one where parents, teachers, administrators, and community members are genuinely thinking together about what’s best for students. That means listening as much as pressing, acknowledging tradeoffs, and recognizing that no one has this figured out. Schools that feel attacked will become defensive. Schools that feel like partners in a shared problem will become allies. The transformation education needs won’t come from gotcha moments. It will come from communities that build enough trust to experiment together.

Conclusion

Where is education heading? In multiple directions at once. Institutional education will fragment, with some schools circling wagons while others experiment radically. Self-directed learning will continue its rise. The gap between what schools teach and what students need will widen substantially before it narrows.

The schools that thrive will be those that stop competing with AI at what AI does well and instead double down on what remains inherently human: judgment, dialogue, collaboration, ethical reasoning, the ability to act in the world rather than just know about it.

I don’t know exactly what that looks like at scale. Neither does anyone else. But I know it doesn’t look like what we have now.

The gap between where education is heading and where it should head—that’s the whole problem. And closing it will require courage from leaders, adaptation from teachers, and dialogue with parents and students who want the best for everyone.