Massive Disruption Now: What AI Means for Students, Educators, Administrators and Accreditation Boards

The choices many colleges and universities make regarding AI over the next 9 months will determine if they survive. The same may be true for schools. (Me)

Co-Founder Educating4ai.com; Co-Developer the AI Boot Camp for Leaders

Co-Editor: Chat(GPT): Navigating the Impact of Generative AI Technologies on Educational Theory and Practice

Most (there have been some noted exceptions) educators were slow to embrace what AI means for the field (K-16+). I think the major reason for this was that people were largely focused on the present and not the future; certainly, if AI models hallucinated at the rate of ChatGPT3.5, only ever wrote in robotext and remained bad at math, they would never be anything more than little toys. The problem, however, is that they didn’t stay the same (they’ve already reduced these problems), and what AIs will be in two years or less, is nothing short of world-changing. While education may have been able to “push through” ChatGPT3.5, and even manage to avoid change in a world of ChatGPT4, both new tools and a recognition of their future means this is something education can longer ignore and many educators are coming around (if slowly).

Just for a minute, consider how education would change if the following were true –

*AIs “hallucinated” less than humans

*AIs could write in our own voices

*AIs could accurately do math

*AIs understood the unique academic (and eventually developmental) needs of each student and adapt instruction to that student

*AIs could teach anything any student wanted or need to know any time of day or night

*AIs could do this at a fraction of the cost of a human teacher or professor

If these were all true, how would education need to change to still be relevant? These are not questions we can ignore because we are getting closer and closer to these all being true. My own prediction for all of these being true is no later than the fall of 2025. I don’t know anyone who thinks it’s later than the fall of 2026.

Fall 2026 is three years away. Do you have a three year plan? Perhaps you should scrap it and write a new one (or at least realize that your current one cannot survive). If you run an academic institution in 2026 the same way you ran it in 2022, you might as well run it like you would have in 1920. If you run an academic institution in 2030 (or any year when AI surpasses human intelligence) the same way you ran it in 2022, you might as well run it like you would have in 1820. AIs will become more intelligent than us, perhaps in 10-20 years (LeCun), though there could be unanticipated breakthroughs that lower the time frame to a few years or less (Benjio); it’s just a question of when, not “if.”

What does this mean for K-16?

Uncontrolled “plagiarism.” Towards the end of 2022 and throughout January-May of 2023, many educators grew suspicious of students who were writing entire papers or substantial chunks of them with ChatGPT and other AIs. We’ll never know exactly how widespread the problem was because many educators did not pick-up on it and students grew more capable of disguising their use of AIs. Starting in the fall of 2023, any lid on that use is about to get blown off: awareness of these tools has massively grown; they are now an embedded part of Office and Google docs; they can write more and more in student voice; entire companies exist that provide AIs to write for the students and guarantee their work can’t be detected by plagiarism detectors; the detectors themselves have huge limits; they discriminate in application (Eaton; Gegg-Harrison); and more and more kids know how to defeat them. As Ethan Mollick noted, the pressure to simply press “the button” and have an AI write for you in Google Docs or Word is just way too tempting (at least for a first (significant) draft), and only minimal effort will be required to pass it off as a students own writing (they can even instruct it to add some grammar and spelling errors ::)).

Cyborg students. Ethan Mollick recently wrote an article about how there are cyborg workers using generative AI tools even where it has been banned by using it on their phones in order to increase their own productivity. Many K-12 schools have banned ChatGPT on school computers and networks, but students can obviously access it at home on their own devices or on their phones at school. “Cheating/plagiarism” aside, these students will, at a minimum, be producing higher quality final products than their peers. And if they take advantage of teaching and tutoring bots to learn more, as many students had started to do even before ChatGPT was released (using human tutors), then they will leave their peers in the proverbial dust: The knowledge and skills cyborg students are develop will be way beyond what their peers are developing, leaving their peers only prepared for work in a pre-AI world.

Harvard recently added bots to a course to support 1:1 instruction. You can see the power of one of the tutors in this video and you can listen to a full podcast on the impact of bot tutors here. See also: Matrix Holograms. And the reality is that these bots will be better than many teachers in many ways.

Cyborg instructors. Educators who understand AI, including how to use it and teach with it in their field, will be the ones who are the best teachers. They will be providing the most relevant instruction, they will attract students who are worried about their future and they will produce the most dynamic and engaging classroom environments and relevant assessments. Educator cyborgs who use AI properly will simply run circles around colleagues who try to teach with pre-AI world tools and with assessments designed for that era.

External education. Education will become inherently more decentralized as students have more and more easy opportunities to learn at very low costs. The traditional school as the central source of knowledge will quickly dissipate (Coxon; Matthews), especially as teaching bots develops. We may see the development of more education action zones , DAOs (Ed3dao) and XR schools (see groundbreaking work by John Kelly, Melissa McBride, Polo Lam and Steve Grubbs). While a high school diploma or a university degree may now represent some certification of a student’s abilities, systems like Learncard.com will be able to do this by providing an electronic record to any employer who wishes to see it. This will be especially meaningful in the K-12 arena, as that is still a chunk of where students are getting their knowledge.

And the more education moves into cyberspace, the greater economies of scale are created. Companies are going to show-up at the tax payer’s door, promising more for less, and they won’t have a terrible argument. Education is a large sector of the economy, and e-learning companies are coming for it.

Social issues. Institutionally, schools will struggle with issues of counterfeit human photos and voices causing significant disruptions, particularly from false accusations and cyberbullying on steroids. Students will struggle from growing social media addiction, as social media companies use generative AIs to build intimate bonds with students and adults (Harari). Beyond the harms of addiction, these intimate bonds will be used to manipulate individuals, even potentially shaking the bonds of democracy.

What does this mean for students?

Formal schooling will still play a role in students’ lives but not forever. At least for another year or two, students will need good grades and high SAT scores to get into a good college. This is unlikely to hold in the future, as students learn more and more outside of school and rely on AIs to complete more and more of their own work. They will also start developing their own businesses at a faster rate. It would be surprising to see a high school drop-out start a multi-million dollar company with only a handful of employees.

Students should be less reliant on schools. Unless their school is particularly innovative (Cottesmore, Arizona State and some others), school is not where students will learn about AI (at least in time, at least enough). Students should look toward outside vendors (and even AIs) where they can take courses in learning to use AI tools. These will have at least great of an impact on anything they are learning at school in terms of future success. Those that do this will have a massive advantage; basic notions of equality and equity are why public schools need to get their acts together and step-up to the plate and prepare for the AI-world.

It should drive college choices. If your college choice is not preparing you for an AI world, then why are you attending the school? Unless it has such a great reputation that will help you secure the job regardless of your skills, why are you going to attend it? You should look for leaders in this area such as Arizona State. If you won’t do a single work task without AI, why should you be taking classes without AI.

In a recent interview, Blake Lawitt, LinkedIn’s Senior Vice President and General Counsel, noted that employers are now emphasizing skills and talents, not college degrees, when hiring.

What does this mean for teachers?

Yes, you could eventually lose your job (or the opportunity for a job). K-12 teachers are not at-risk of immediately losing their jobs, especially given the global shortage of teachers. And laws require that students attend school, parents need places to bring their kids, and students need social interaction. Younger students clearly still need to be taught at least somewhat by humans.

But there will be pressure. Will there still be value to learning a language when there can be instant translation in your ear piece? We know students are already using specialized bots to practice their language skills.

We do know that schools will always need teachers who can facilitate learning and human interaction. More and more people say this will shift to a “coaching” model (Fitzpatrick; me in January 2023: “Educators as Coaches”), where the teacher facilitates learning in a three way conversation between student, teacher, and AI.

Teachers may not lose their jobs, but the nature of what we need K-12 teachers to do will change and individuals who can adapt to this environment will be the best (and perhaps the only) teachers.

Professors are obviously at much greater risk than K-12 teachers, as the price of a college education is completely unaffordable for some (absent hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt). Smaller universities are already struggling financially, and the ability to learn from bots at a fraction of the price will (and should) be tempting for many students. Universities outside of the top 50 that don’t adapt to AI will perish; those that do will thrive. The choices many colleges and universities make regarding AI over the next 9 months will determine if they survive.

Learn. Faculty should embrace professional development/learning opportunities and take initiative to learn about the technologies from the various online resources. There is a wealth of accessible information. Some lament that this is “another thing to do” post-COVID, but the reality is that faculty who do not adapt to the world of AI aren’t going to be very good teachers. And, regardless of what anyone may think of AI as a job responsibility, everyone will live in an AI world and should want to understand what it means to live in that world.

What does it mean for administrators?

It means hard questions at board meetings. It’s already happened. Parents have shown-up at school board meetings and asked what a district’s AI strategy is. That’s probably the fairest question that has even been asked at a school board meeting. Professors will soon be receiving emails about fall AI policies and the answer will impact whether or not students take the class.

A lot of how students learn will be rethought (or at least it should be). A lot of what is written about how students learn in school is based on the assumption that the primary driver of the learning is the teacher, either through a lecture or through a more dynamic classroom; regardless, it is the instructor who is driving things. Very soon (maybe now), every student will also have their own learning bot that helps them learn classroom material. And to push it farther, “students (will) transition from being mere ‘curriculum consumers’ to active ‘curriculum co-designers’, manifesting a shared agency between teachers and students.” There isn’t much in the theory of how students learn that assumes they have dynamic 24/7 tutors. To highlight how much education will change relative to the status quo, consider:

At the heart of this transformation is the creation of novel relationships between Human Intelligence (HI) and Artificial Intelligence (AI), which define the architecture of learning. These synergistic relationships, enriched by Collective Intelligence (CI), shape a vibrant, dynamic learning environment where teachers evolve from traditional instructors to empathetic tutors, prompting student agency, co-agency, and collective agency — ‘transforming teaching to mentorship’.

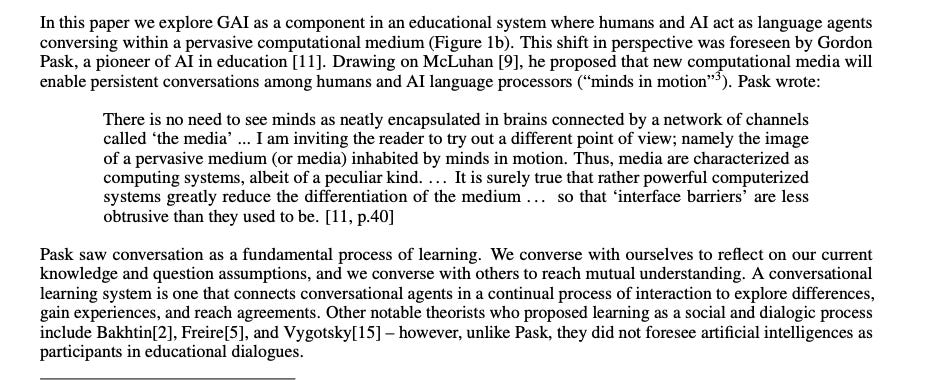

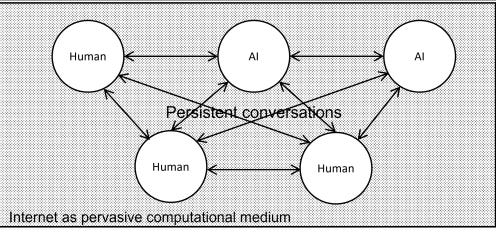

Dr. Mike Sharples contextualizes the idea this way:

This is very Vygotskyian (Clark).

It means assessments have to change. Single-artifact assignments can be done better by AIs than by students (or at least soon they will be able to). Trying to use AI detectors to stop student use is not only a recipe for failure but deprives students of real-world skills. New assessments need to be developed, perhaps using technology. I like this one: “Valerie Shute’s notion of stealth assessment goes some way to providing a means of effectively assessing the trajectories of student learning. Her work has focussed a lot on video games, where many aspects of the process of working towards a goal are evident. Think of how players accumulate points, defeat enemies, or solve problems in a video game and how those processes accrue over time. There is much to like about Shute’s ideas but they heavily rely on technology to do the work of tracking these trajectories.”

Leon Furze has started writing about this, incorporating work already done by the Australian government (Australia is one of the leading countries on AI in education) that he links.

Provide professional development opportunities. All educators need professional development in AI related to its impact on education. Only 4% of teachers report receiving professional development on AI!

Infuse soft skills. There is no consensus (or even a way of knowing) what content students will need to learn in an AI world in five years. There is agreement, however, that (soft) skills such as communication (which may now include human-computer interaction), leadership, and critical thinking will be needed in a world where we all will have 5 AIs who are smarter than us (Lecun) doing our work. Professors should be integrating teaching these skills into every course and K-12 administrators should require it. Rebecca Roland writes:

Raising children in this way requires a full re-envisioning of the way we understand success for children. Such a vision involves thinking much more about children’s abilities to judge the ethics of a situation, to apply empathy in difficult times, and to explore the short- and long-term consequences of actions. It requires helping children know what it means to have compassion, and how to recognize and support well-being and others and themselves. It means helping them develop the skills to handle complex generational challenges such as the environmental crisis and, ironically, the benefits and dangers of AI. And, most fundamentally, it involves helping them know what it means to love and care deeply and authentically for others, and to know and love their authentic selves. Instead of diving further into the airbrushed world of Instagram images, we need to support them to love and care for their authentic realities.

In school and at home, we will also need to assess them differently. We will need to focus on the quality of our conversations, in terms of how they support empathy, compassion and critical thinking. We need to emphasize the everyday back and forth of our discussions, as they reveal both how much children understand and how they feel. We likely need to get away from data-driven metrics such as “How often does this child raise his/her hand?” and toward reflective listening that focuses on what children are trying to communicate. Rolland

Jack Ma argues that it is better to focus on soft skills rather than to try to compete with machines.

The World Economic Forum argues that students need to develop problem-solving, collaboration, adaptability and resilience skills. Israeli Historian Yaval Noah Harari argues these skills are essential in a world of rapidly advancing AI because job opportunities will constantly change and people will need to continually reinvent themselves. Harari lecture

These skills include learning to communication with bots. Tom Rogerson, Head of the Cottesmore School, adds, “It’s more important than ever to teach people how to live a good life and how to collaborate with other people and collaborate with artificial intelligence and robots.” Daily Telegraph [everyone should read this article].

Infuse AI skills. Every K-12 teacher should be required and every professor should be encouraged (sorry, that’s just how that plays out) to use AI in the classroom for at least one assignment. If some really hate it, they could have students write essays about its limitations (in their own words :)), push it for factual errors and try to trip it up on a math problem. They can even try to get it to break-up with their significant other. Given the enormous impact AI will play in future elections (Marcus; something there is a consensus on), how could you teach civics and not teach about AI?

Purchase some AI textbooks and experiment. Interactive textbooks are here and they’ll work well with bots and extended reality learning spaces.

Be creative. Even the most restrained academic institutions can find a way to integrate AI. K-12 schools, especially public schools, will be limited by the law to any adjustments they can make regarding academic instruction, but even those can provide professional development opportunities, require that AI be infused into one assignment, integrate the teaching of skills into courses, and provide instruction in AI literacy. Students are going to inevitably use AIs and if we don’t teach them to use them properly they won’t be “benevolent servants.”

Some schools may fear regulations (X regulation effectively prohibits ChatGPT use), but they should be creative and find a way. There are many generative AI tools that don’t require a log in (preplexity.ai, you.com) or have age restrictions. Aggressive districts are using parent permission forms to overcome barriers. Figure it out! The alternative is to be irrelevant.

Provide opportunities for AI literacy. I’ve written extensively about the importance of AI literacy and calls for AI literacy are being heard from more corners. Administrators could offer it as a course in their schools, provide online options (we have a whole course for individual students or schools), or partially infuse it into existing courses as Hong Kong is doing. We can help you a lot with this (info@educating4ai.com) :). Pew Research just wrote a report about the changes society is likely to experience in an AI-world.

Put “plagiarism” in perspective. AI can write as well or better than most students (and its abilities will only grow). The writing skills 99% of people need to develop will decline. But, students will still need to learn to effectively communicate in a written form both with humans and computers. To support and test this, students will need to do some writing on their own (especially in the early grades) and will need to learn how to write without AI (at least some of the time). Stopping student plagiarism in these instances is important, but an anti-AI plagiarism policy cannot be your AI policy. Do you want to be the school that hires a Head of AI or do you want to be the school that spends all day fighting student plagiarism? When you work on your institution’s AI policy/guidelines, you should spend (at most) 5% of your time on how you will manage plagiarism.

Prepare for the mental health fallout. We already discussed the mental health toll addictive bots will have for students. Teachers will also be stressed about the impact it will have on their jobs (regardless of whether or not they will lose their jobs AI will change their jobs), parents will fight with teachers and administrators about AI usage in the classroom, education will require radical adaptation, and people probably need to be generally prepared to constantly change their jobs. People are not built for that, and the mental health problems we are already seeing will grow.

Hire a “Head of AI.” The Cottesmore School, one of the leading boarding schools in the UK, recently advertised a position for a “Head of AI.” Job descriptions will vary at this point, but every academic institution should hire a Head of AI that can stay up on current developments, including trends and AI models; share ideas about the future of AI in education; support teachers, students and the broader community; attend relevant conferences to gain more knowledge; make informed decisions about what apps to purchase; and facilitate the integration of the institution into the AI world in order that the institution can remain relevant and competitive.

Develop an AI policy/framework. Given the rate of change and the indeterminacy of the future, it is difficult to develop AI policies for educational institutions, and strict policies will limit necessary experimentation, but working to develop AI policies force essential thinking and trigger a wider discussion among the entire community. Private schools started this in March (Moran) and some examples (Furze, Cottesmore) already exist.

Include everyone. This is about way more than Edtech, and very few people in EdTech are going to have any experience with interactive, dynamic learning bots. All ideas should be on the table. College students certainly have opinions (ESU; conference).

Prioritize this. Preparing students both for the AI world and how to work in it academically is arguably the most pressing issue schools are facing and they must find time for this at the start of the academic year. The British International School of Tunis collapsed its curriculum to spend an entire week on AI.

Understand that student use cannot be controlled. Arguably driven by tightening liability laws, concerns for school safety and greater standardization of instruction, and generally heightened surveillance, schools have exercised more and more control over their students. As schools found with ChatGPT, they can’t control student access to information and use of AI technologies. Some schools will respond to this by introducing their own AI systems for students to use, but students will also work outside of these systems.

Understand you cannot plan this out. There is a lot of planning that occurs in education: people forward ideas; someone takes up the idea; support is gathered for the idea; the idea goes to a committee; the committee debates the idea; further input is sought; an implementation plan is designed; other things come up so implementation is delayed; implementation occurs. There are two problems with this in education. One, We’ll be at ChatGPT6+ by the time all of this happens and the ChatGPT3.5/4 plan will be irrelevant. Two, the intersection between AI and education is arguably at singularity: the point at which the development impact of the technology becomes completely unpredictable. [Note:: Singularity is also defined as the time at which we reach ASI].

Host An AI “Roundtable.” A lot of what I wrote above will not be surprising to many readers. It will be shocking to people who do not yet have ChatGPT accounts. Educators are all over the map with their knowledge related to generative AI in education. Educational institutions should host “round tables” where they discuss lead open forums with educators about generative AI. Open Forum questions might include – Have you used ChatGPT? Do you plan on using GAI to support your work this year? Do you plan on encouraging student use? How do you think students should be allowed to use it? What do you want to learn about it? What excites you about AI? What scares you about AI? What type of professional learning do you want?

What does it mean for governing and licensing bodies?

Don’t be irrelevant. If you don’t change education standards at all, your standards may become completely irrelevant. If your standards are irrelevant, your institution is irrelevant.

Plan to adjust your standards. It is difficult to say what standards to adjust and how to adjust them, but I’ll provide a couple of examples for considerations. (1) What are the writing standards for students writing with Copilots? (2) What are today’s AI literacy standards?

What matters in an AI world? Modern education standards reward cognitive abilities: the ability to master content and to be intelligent. In a world where cognitive labor is highly valued, this makes sense. But if we are all going to have 5 AIs that are fifty+ times smarter than us doing our work, how valuable is our cognitive ability? It will certainly still have value, but maybe the most creative among us or those with the best interpersonal skills should get into Harvard?

Raise standards. Students should be able to accomplish way more and better work in a shorter period of time using AIs. We should expect better work and more learning from students.

Think ahead. Would it matter if 100% of the students in the US could meet the standards of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) if they couldn’t live in an AI world? Would an employer rather hire a high school graduate without AI skills or a high school dropout with AI skills?

What does it mean for everyone?

Use AIs. 90%+ of people who are using AIs today learned how to use them on their own. You can learn a lot from basic experimentation and reading online. There are also many inexpensive course options to help you with your learning. Teachers can use AIs for many things, including lesson planning, contention creation, assessment design, slide shows, grading and feedback. Just try it out! There is comprehensive coverage here and this site has detailed things teachers can do.

K-16 collaboration. There is some emerging bifurcation about AI means X for K-12 and Y for higher education. There are certainly differences, but I wouldn’t see things as so bifurcated. K-12 already started reaching up, with students taking college classes in high school and using AP and IB credits for college credit. Universities already started reaching down as they see more and more students enter college without basic academic skills. Plagiarism-related issues and the need for assessment changes impact both. There should be more collaboration on this issue.

Every teacher preparation program should include a course on preparing teachers to coach students in a world of AIs.

Important Things to Understand

Students still need to learn “stuff.” There is an argument out there that education needs to focus on skills and not content because AI will be able to do much of what we do and there has not been enough focus on skills even before AI. Skills are probably becoming more important, as AIs will be able to do a lot of what we need to do, but I don’t know anyone who doesn’t think students need basic math and science skills and subjects such as history are important to bind students to country and culture. English and humanities courses are needed to help students think through the essential elements of what it means to be human.

The current system provides some valuable measurement. No one is excited to hire the valedictorian of the high school because she mastered the high school curriculum. People are excited to hire the valedictorian because they know she follows directions, completes her work, is at least reasonably intelligent, takes advantage of opportunities, likely works well with others, and strives to improve. The current system doesn’t do a bad job of sorting in this way.

Some people are coming for traditional schools. Some wonder why people would release and promote tools that undermine schools. In my case, I think it’s because schools need to integrate into the AI-world or they won’t survive. In other instances, people are upset about costs (taxes or tuition), graduation rates, percentage of students “passing” national assessments, the relevance of curriculum and the structure of schooling. Educators need to understand that many people (Diamandis) are “coming for” traditional schooling. AIs have created an exigence in education and those who have opposed the current structure have a great time to take aim.

Additional References

Bojorquez., H. Martinez, M. (2023, May 31). The Importance of Artificial Intelligence in Education for All Students. Language Magazine. https://www.languagemagazine.com/2023/05/31/the-importance-of-artificial-intelligence-in-education-for-all-students/

Coxon, D. (2023, March 3). 3 Reasons Teachers Should Not Fear AI (And One Reason They Should). https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/3-reasons-teachers-should-fear-ai-one-reason-darren-coxon/

B. Eager and R. Brunton. Prompting Higher Education Towards AI-Augmented Teaching and Learning Practice Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 20(5), 2023. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.5.02.

Eaton, L. (2023, June 22). Ready or Note, Here AI Come - An Institutional Approach to Generative AI.

D. Hendrycks. Natural selection favors AIs over humans. arXiv preprint https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.16200, 2023.

Hildenbrandt, E. (2023, June 22). Iowa professors say students must be educated about artificial intelligence. Iowa Capital Dispatch. https://iowacapitaldispatch.com/2023/06/22/iowa-professors-say-students-must-be-educated-about-artificial-intelligence/

Kelly, J. (2023, June 14). Future Education 3.0 - From Starfield Direct to Tears of Kingdom: Mapping the Path Ahead for Education in Video Games. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/newsletter-16-future-education-30-from-starfield-direct-john-kelly/

Kimova, B. Saraj, P. (2023, March 22). The use of chatbots in university EFL settings: Research trends and pedagogical implications, Frontiers of Psychology, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1131506/full

Koehler, T. Sammon, J. (2023, June 16). How Generative AI Can Support Research-Based Math Instruction. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/using-ai-math-instruction?

J. Rudolph, S. Tan, and S. Tan. ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education?. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 2023.

Sankey, M. (2023, June 21). Embracing AI in Assessment.

T. Trust, J. Whalen, and C. Mouza. Editorial: ChatGPT: Challenges, opportunities, and implications for teacher education. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 23(1):1–23, 2023.