Losing Control: The Fear of AI and the Reality of Ourselves

Maybe it’s time to hit the pause button — not on innovation, but on our own violence.

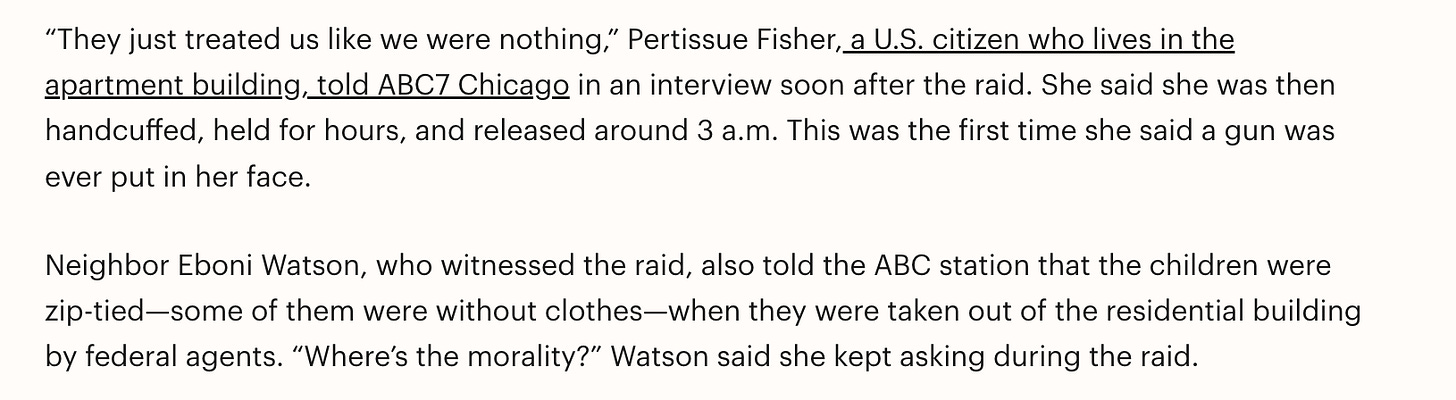

In the early hours of an October morning, helicopters thundered above Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. Federal agents in tactical gear flooded into apartment buildings as part of a multi-agency ICE operation.

Residents woke to flashlights and shouts. Videos later showed officers zip-tying men in their underwear, dragging screaming children from beds, and throwing pepper balls down hallways.

The raids were billed as “targeted enforcement,” but in practice they swept up citizens and immigrants alike — a display of power more suited to a war zone than a city street.

More is to come. Our annual immigration enforcement budget is $40 billion per year. This is the same size of South Korea’s military budget. South Korea has the 10th largest military in the world.

It’s an image of control — or at least, of people trying desperately to exert it. The irony, of course, is that it feels like the opposite.

At the same time that policymakers and tech leaders warn that we may soon “lose control” of artificial intelligence, scenes like this suggest that we’ve already lost control of ourselves. We fear that machines will harm humans. Yet everywhere we look, humans are harming one another — not through algorithmic rebellion, but through ordinary violence, institutional breakdown, and moral exhaustion.

As released by the White House, Welcome, Grim Reaper.

The Fear of Losing Control

Ever since the Future of Life Institute’s open letter called for a pause on training systems more powerful than GPT-4, the language of “control” has haunted the AI debate. The argument is straightforward: if artificial systems continue to evolve faster than our capacity to align them with human intent, they could become uncontrollable — acting in ways we don’t predict, can’t stop, and may not even understand.

In one sense, this is a prudent fear. History offers no shortage of cases where technological progress outran moral foresight. In another sense, though, the conversation feels almost detached from reality. We worry that intelligent machines will one day kill or oppress us (If Anyone Builds it, Everyone dies) while human beings — fully conscious, fully accountable — are already doing those things to one another.

A World Slipping Out of Human Hands

It’s not just ICE.

In Manchester, England, a man rammed his car into pedestrians before lunging at worshippers with a knife at the Heaton Park Hebrew Congregation. Two people died, including one shot accidentally by police amid the confusion. Here, a gunman in Grand Blanc Township, Michigan drove his truck into a Latter-Day Saints meetinghouse, set it on fire, and opened fire on congregants.

In Utah, conservative activist Charlie Kirk was assassinated while speaking on a university campus — a killing that unleashed a fresh wave of conspiracies, threats, and calls for retaliation. Two students were killed in a school shooting the very same day.

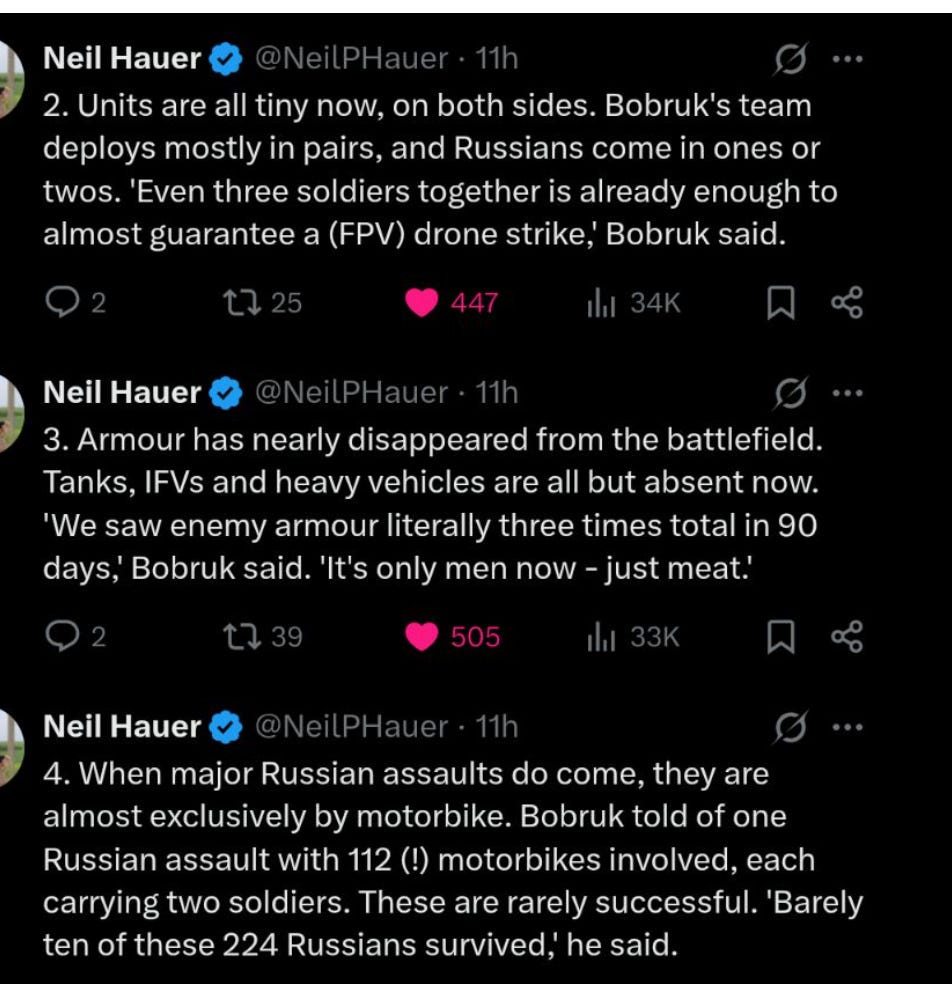

And overseas, the bloodletting continues. The war in Ukraine grinds into its fourth year, with tens of thousands of civilians dead and entire cities turned to rubble.

In Israel and Gaza, the renewed fighting has pushed human suffering to unbearable extremes — families buried beneath concrete in Rafah, Israeli hostages executed on camera, aid convoys shelled as they try to reach the hungry.

And at home, some believe the United States remains a nation in permanent low-grade civil war with itself. The gun homicide rate is twenty-six times higher than that of other developed nations. Nearly 18,000 Americans are murdered with firearms each year. Schools drill children to hide from active shooters; grocery stores and churches have evacuation plans. The line between public space and potential killing ground grows thinner every week.

These are not freak events. They are symptoms of a deeper unraveling — an erosion of restraint, of trust, of empathy, of an inability to resolve differences beyond killing. And the systems meant to keep us safe — political, legal, religious, civic — seem increasingly incapable of managing the forces they unleash.

The Paradox of Human Control

When we talk about “losing control of AI,” we mean a technical or existential loss: an algorithm pursuing goals we didn’t intend. But when we lose control of ourselves, it’s a moral and institutional failure. It’s the point where systems built to serve the public — government, religion, law enforcement, media — start serving only their own survival instincts.

The ICE raids in Chicago show this vividly. A government designed to protect rights now terrorizes families in the name of security. The Manchester synagogue attack shows what happens when ideology overwhelms empathy, when grievance becomes an excuse for slaughter. The assassination of Charlie Kirk reveals how politics, stripped of moral ballast, slides toward war by other means.

And wars like Ukraine and Gaza demonstrate the collective version of this breakdown: entire nations locked in spirals of retaliation so complete that the very idea of restraint feels antiquated.

If control means channeling power toward life rather than destruction, then the evidence suggests we’ve already ceded it.

Why This Matters for AI

This is not an argument to dismiss AI risk. It’s the opposite. It’s an argument that our inability to control ourselves makes the challenge of controlling AI infinitely harder.

We already know how feedback loops work. One violent act begets another, each justified by the last. Social media outrage fuels polarization, which fuels violence, which fuels more outrage. Now imagine those dynamics running on algorithms that adapt faster than we do. The same species that can’t moderate its own impulses is about to engineer a system capable of amplifying them at planetary scale.

The fear isn’t just that AI will act autonomously, but that it will act too much like us — optimizing for dominance, speed, and self-preservation. It will mirror our incentives, our blind spots, our taste for escalation.

Calls for AI “alignment” assume there exists some coherent moral compass to align it with. But look around: what, exactly, would that compass be?

Everything is an emergency.

A national security threat.

A crisis.

If we can’t even agree on what counts as life worth protecting, how will we instruct an artificial mind to value it?

Control as Humility

We typically think of control as the ability to make things happen - to execute, to achieve, to impose our will on the world. But what you’re pointing to is something more fundamental: true control might actually be the capacity to stop ourselves from acting. It’s the difference between a river that floods destructively and one that’s been channeled - the power is the same, but one has direction, the other just momentum.

A martial artist’s greatest skill isn’t in striking, but in knowing when not to strike. A surgeon’s expertise includes knowing when not to operate. A writer’s craft involves knowing what to cut. The restraint isn’t weakness - it’s the evidence that someone has moved beyond reactive power into genuine agency.

When we can act but choose not to, we’re demonstrating something deeper than capability. We’re showing judgment, wisdom, self-knowledge. We’re proving we’re not slaves to our own momentum, our habits, our conditioning, or the social pressure to “do something.”

In human terms, we call it morality. In technical terms, we might call it alignment. Either way, it’s the art of setting limits.

But restraint is precisely what modern society has forgotten how to do. Our politics rewards outrage, our markets reward acceleration, our media rewards spectacle. We don’t pause. We push. The machine mirrors us because we built it in our image.

If we can’t restrain ourselves — our violence, our appetites, our desire for control — we have no ability to restrain the systems we create.

Drawing Red Lines — For Machines, and for Ourselves

In September 2025, a coalition of AI safety researchers launched the AI Red Lines Initiative, proposing a global agreement on a set of practices that no responsible actor should cross — the deployment of fully autonomous weapons, systems capable of deception, models trained to manipulate public opinion, and other irreversible risks. The idea is elegant: before we push forward, we must decide what not to build.

It’s a sensible call — but it raises a harder, more haunting question: what are our red lines?

We once had them.

Never again genocide.

Never again chemical weapons.

Never again the targeting of civilians.

Yet from Kharkiv to Chicago, those lines have faded into suggestion marks. Even the simplest moral prohibitions — do not torture, do not kill or harm children — have become negotiable under the pressures of ideology, fear, security, and political gain.

If we cannot uphold red lines for our own conduct, how credible are we in drawing them for machines? If the meaning of “unacceptable harm” shifts with the news cycle, what hope do we have of encoding it into code?

Before we sign global accords on what AI must never do, perhaps we need to renew the ones about what we must never do.

The Final Mirror

It’s easy to imagine that the real danger lies in machines surpassing us — that one day AI will wake up and decide it no longer needs its creators. But perhaps the darker truth is that it already mirrors us too perfectly. Every war, every raid, every act of cruelty is a program we’ve been running for centuries — recursive, self-replicating, and increasingly efficient. Imperial boomerang. We don’t need artificial intelligence to end humanity; we seem to be doing just fine on our own.

So yes, let’s debate moratoriums and red lines. Let’s decide what technologies should never be built, what systems should never be unleashed. But before we draw those lines for our machines, perhaps we need to draw them for ourselves.

Maybe it’s time to hit the pause button — not on innovation, but on our own violence.

To stop long enough to ask who we really are, what kind of world we wish to preserve, and what it means to be human when power has outpaced wisdom. We need space to think about how we live with one another, how we resolve conflict without erasure, how we manage scarcity without cruelty, and how we make peace something more than the silence after destruction.

The truth is that our most urgent moratorium is moral, not technical. We need a pause long enough to remember how to live before we teach something else how to. Not as preparation for some future AI crisis, but as intervention in the human crisis happening right now.

The bitter irony: we’re so afraid AI will kill us that we’ve missed the fact we’re already doing it to ourselves. If we can’t stop that, alignment is just a word we’ll carve on the tombstone.