How to Help Students Learn to Think Using AI

We need to teach them how to interact with AIs in a way that supports their critical thinking and the development of their metacognitive skills.

Thanks to everyone who has supported this blog either through a paid subscription and/or sharing it with others.

A good amount of educational assessment has always focused on assessing a product: a paper; a presentation; or a test.

In the process of preparing to produce the product, students were supposed to be thinking, and that’s one of the ways their critical thinking skills were supposed to develop.

Today, we have AI “tools” that can produce products (and even pass tests), leaving many to worry that students will simply use the tools to produce the products, short-circuiting critical thinking. This is certainly happening, despite the AI detector cottage industry that has arisen.

The answer to this reality by some educators (all are not willing to accept it) is to help students integrate AI into product production, both so they end up with a better product and so they are prepared for the world of work. This is certainly important, even if we don’t know where the AI-human product production balance will lie five or ten years out.

But I think we need to consider helping our students work with AIs beyond assisting in product production. We need to teach them how to interact with AIs in a way that supports their critical thinking and metacognitive development.

The rest of this post is an example of how to do that.

_____

The other day I worked with some debaters on how to use AI apps to improve their debating. We started with ChatGPT, as all but two of them had used that.

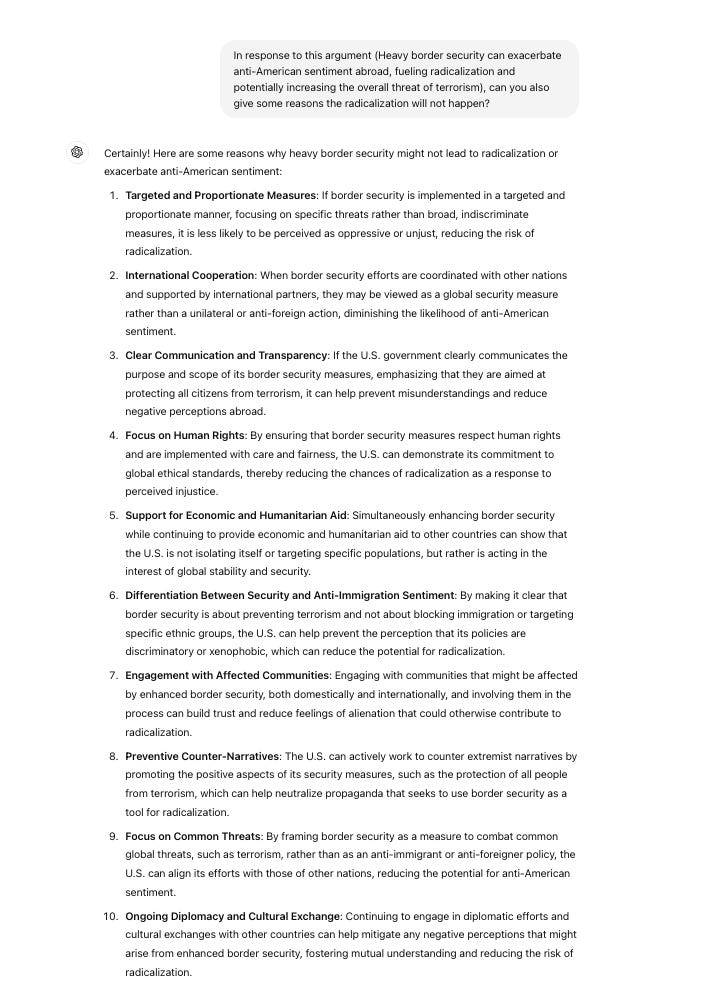

I started with a simple prompt, asking ChatGPT to generate 10 responses to an argument on their debate topic.

Some people may be reading this and think: That is so wrong; it did the debaters’ work. Some debate coaches have had that reaction to these tools.

Two notes.

(1) I then asked them to pick one argument they would use in the debate and one argument they would not and to explain why they would use it and not use it. We did this live, and this required them to not only have developed some background knowledge on the topic they could use reason as to why but also to think.

(2) Most debaters would not come up with anywhere close to 10 arguments on their own. The top 10% of debaters could, but most would only be able to come up with 10 using support/ideas from their coaches and other debaters (knowledge doesn’t normally spring out of completely original thought). This just makes it possible for that to happen faster and allows students who don’t have all of those supports to compete on a level playing field.

Of course, we didn’t stop here. I asked it to generate responses to the responses.

After it generated the responses, I asked the students to pick a response and explain why it was a strong or weak response.

For #6, one of the students pointed out that while it was useful to point out that although border surveillance could potentially avoid the impacts of radicalization, there was no direct response to the claim that border surveillance would cause radicalization.

I explained to the students that just because a response to an argument wasn’t originally made, they could ask ChatGPT for arguments that more directly respond. During this time, we also discussed the importance of creating a targeted prompt that focused on being specific about what they wanted.

We spent some time talking through each of these arguments and about how none of them were great. We then concluded that the original radicalization response might be a strong one because it was difficult to answer.

Thinking through all of these possible arguments, including what responses are weaker, requires students to think critically and sets them up for being most prepared for their debates.

Of course, I asked ChatGPT for the responses to the responses.

Then we discussed responses to responses, including their strengths and weaknesses.

In addition to using ChatGPT to help construct and devise arguments, we also used it to help prepare questions in the debate.

We then discussed which questions would likely be most useful, how different questions would be more useful depending on the specifics of the arguments, and how they might want to adjust the wording of the questions. Students would not have the time to ask 10 questions in the debate, so they would have to carefully choose which of these questions to ask.

It was useful that ChatGPT added the purpose of the question, as I always try to get students to think about why they are asking a question.

Although questioning worked reasonably well with the above prompt, the students struggled with prompting that would generate useful questions.

“About.” Ask me questions “about” X argument was a common formulation of a student prompt “(I need questions about border surveillance and terrorism”). This was a little bit useful, but it generated questions to create an explanation for both sides of the debate rather than questions that would help undercut an argument.

Lacking context. Sometimes they would ask something like, “Can you give me questions that undermine the argument that border surveillance is good” without specifying the reason the other team is arguing it is good (reducing terrorism, crime, the arrival of more low-wage workers, etc.). This produced vague and largely useless questions. Often, they forgot to include that it was for a debate or that they were in high school, which led it to produce some general academic questions related to the issues.

Problems with their initial prompts created opportunities to teach about the importance of contextualization in prompting.

—

Of course, ChatGPT isn’t just useful for generating argument ideas. As mentioned, there is a Crossfire/questioning period in debates that all students participate in. In Public Forum debate, this questioning period constitutes 25% of the debate and, unsurprisingly, ends up being weighted more by less experienced judges.

Despite this, students spend more time preparing their arguments than for crossfire. In an attempt (perhaps a futile one) to get the students to practice crossfire more, I showed them a basic prompt they could use to practice and get feedback from ChatGPT.

I think ChatGPT gives decent feedback on the hypothetical student’s answer to the question.

I showed the students that the system can understand (I use that word loosely) what they are responding with and will know if the response is very weak/non-responsive.

In Grand Crossfire, all four students participate in the Q&A at the same time. I made this short video from the image above to represent that.

Some concluding thoughts —

(1) Yes, we then worked on researching these arguments using Perplexity. I’ll write about that in another post.

(2) The students struggled with the interactive nature of the prompting. Unsurprisingly, their original prompts were like keyword searches, and they didn’t think to try rewriting a prompt if the first prompt didn’t get them what they wanted. I spent a lot of time talking the students through the weaknesses of their prompts and how to strengthen the prompts, all of which required critical thinking. In many ways, it’s no different than being specific in an argument you develop.

(3) I had to anthropomorphize ChatGPT a lot. You may be rolling your eyes, both because I did that and because you don’t think I “had to.” But I did it because the students were struggling both with continuing to think of it as a search engine and because they were struggling with any sort of dialogue with the system.

A few times when students produced very vague prompts that weren’t helpful, I asked them what they would do if they asked me a vague question and I gave a vague response. A few immediately said they would ask a more specific question. Then we did that with ChatGPT.

Maximizing the usefulness of a Chatbot requires asking good questions and having a dialogue with it. These are skills that are important to teach. The more thinking and intentionality you put behind your prompt, the more useful of a response you will get. This applies to both human and machine interaction.

(4) All but two of the students had used ChatGPT before the class, but none had previously heard the term “hallucination” and understood that Chatbots can make factual errors. This highlights the need for AI literacy.

(5) Whether or not students use ChatGPT to think depends on the class assignment. If the assignment had been the equivalent of “write a speech” or “write a paper,” ChatGPT or another AI could have done a reasonable job. When the assignment is to debate, the focus becomes the process and students are incentivized to use AI as a preparation partner in a way that enhances their critical thinking.

(6) Imagine this happens all in voice. There is some advantage to seeing the flow of the arguments in the tables above, but all of this can easily be done in voice, especially during the practice Q&A period. I think that if students use it in voice, it will be easier for them to see it as a dialogic partner.

(7) Using AI in the ways described allows AI to enter the educational arena as a Coach, Tutor, Peer, and Mentor (Mollick & Mollick), as part of a dialogue loosely referred to as ‘generatavism’ (Pratschke). There is a strong current of educational theory that suggests learning occurs in the dialogue (Vygotsky, Freire, Bakhtin, others), and this shifts more of academic assignment to the process. We cover how AIs can function in the educational system in these ways in more detail in our book.

(8) Human teacher. In the above, the human teacher becomes a facilitator of learning with AIs added in as described in #7.

(9) This is additive. As a debate coach/teacher, I see the role of AIs as entirely additive.

(9a) While the role of the human coach/teacher is retained, students can use AIs as dialogic partners 24/7 to support argument development and improve their skills (more systems are emerging that also provide support for the performative aspects of debate).

(9b). This isn’t subtractive. Debaters develop their arguments/questions/ideas in collaboration with other students (“peers”) and coaches/teachers. Integrating AI into the process (9b1) accelerates that (more potential arguments produced faster), (9b2) allows the output to occur at their level (age/grade/debate experience), (9b3) makes the support available 24/7, (9b4) allows anyone with a phone or computer (almost every kid) to access coaching support, and (9b5) adds additional voices to the preparation.

Any student who tries to use it in a subtractive way as a substitution for their preparation will be at a disadvantage in their debates just as they would be if they only used materials produced by teammates or coaches.

(10) Some argue that AI shouldn’t be introduced to schools until its educational value is proven through studies. We don’t need a study of the above. It’s common sense. In this case, introducing more intelligence to a school setting helps develop the intelligence of the students. They interact with the AIs to develop their debating skills the same way they would interact with a human, except potentially even in a more scaffolded manner.

See also —

Coverstone, Alan. (2023). AI & critical thinking. In Chat(GPT): Navigating the Impact of Generative AI Technologies on Educational Theory and Practice.

Very good post, Stefan. Can we translate part of this article into Spanish with links to you and a description of your newsletter?

Great article. The point about getting people to think correctly about the role of AI in education is critical. Knowing how to productively use these tools will be very important to future employability.

I wrote a more general article on the importance of teaching kids “AI Delegation” skills that you may find interesting:

https://open.substack.com/pub/aipdp/p/ai-delegation-the-skill-our-kids?r=23f0sa&utm_medium=ios