GPTs for Everyday Needs: Using a GPT to Analyze Debate Judge Philosophies. And why is this important for everyone.

"If you believe my decision was wrong punch me in the face".

[Join more than 1,000 people who have downloaded our report]

TLDR

*Build Bots/GPTs and use them

*AIS “understand” humor

*Base knowledge and questioning are key to using bots well.

*AI can do a lot of very useful stuff quickly. We are going to have to learn how to take ourselves to the next level with AI.

Last week, I was asked by some students from China who will be competing in this month’s swing of large and prestigious debate tournaments (Penn, Berkeley, Stanford, Harvard) to talk to them about how Public Forum (PF), a debate event, judging trends have changed.

This is significant, as PF was originally started as a reaction against the specialization in other formats of debate that focused more and more on using a lot of evidence, high rates of speed, and technical maneuvering through the arguments. Well, kids being kids pushed the PF debate this way as well. [Yes, you are right that the elders are again rolling their eyes about “kids these days” who have overthrown them and taken control of their own learning.].

I started by just writing up a few notes about the changes and realized I could skim through some online judge philosophy statements that are in a centralized place (tabroom.com) and I chose last year’s Tournament of Champions (TOC), a highly competitive championship for teams that travel nationally during the year, as a place to gather judge philosophies from.

While skimming through and taking a few notes, I realized that I could just quickly convert all of the judge philosophies (JPs) to a PDF (some quick clicks enabled the creation of a master document) and create a chatbot in the GPT Store to analyze them. I had used a combination of GPTs earlier this week for something else and just had to remember to keep using them :)

I did that, and there are some lessons to draw from it.

*Specific training data is essential. Even though I didn’t think it would work, I first asked both ChatGPT4 and Perplexity to share some trends in current Public Forum debate judging. It did as I expected. It provided some vague and useless information. Basically, it said that PF debate judges like good arguments that are well explained, which doesn’t provide much guidance. Without training this on actual judge philosophies, it wouldn’t have worked.

*Using GPTs solved document length limit problems (also in Claude). My first thought was to simply upload PDF of JPs to ChatGPT4 and ask it to analyze the PDF, but it said my request was too complicated and gave up after three tries (it did make three attempts). I then tried Claude, but Claude said the document was too big. I was frustrated and almost gave up, but then I thought, Make a GPT with ChatGPT4!

So I made a simple GPT, uploaded the PDF into the GPT, and started asking it questions. First, I asked it to summarize the document, highlighting different things that were important to judges. It did that, but it was sort of meh. It just made a list of some general things with a one-sentence explanation. But then I started asking specifically about controversies in PF debate: Paraphrasing evidence vs. direct quoting; tech vs. truth; how debaters should dress. When I did that, it “killed it” and gave me a lot of. useful information. See below.

*GPTs can directly quote. Without asking, it often provided direct quotes from the JPs to support its’ summaries.

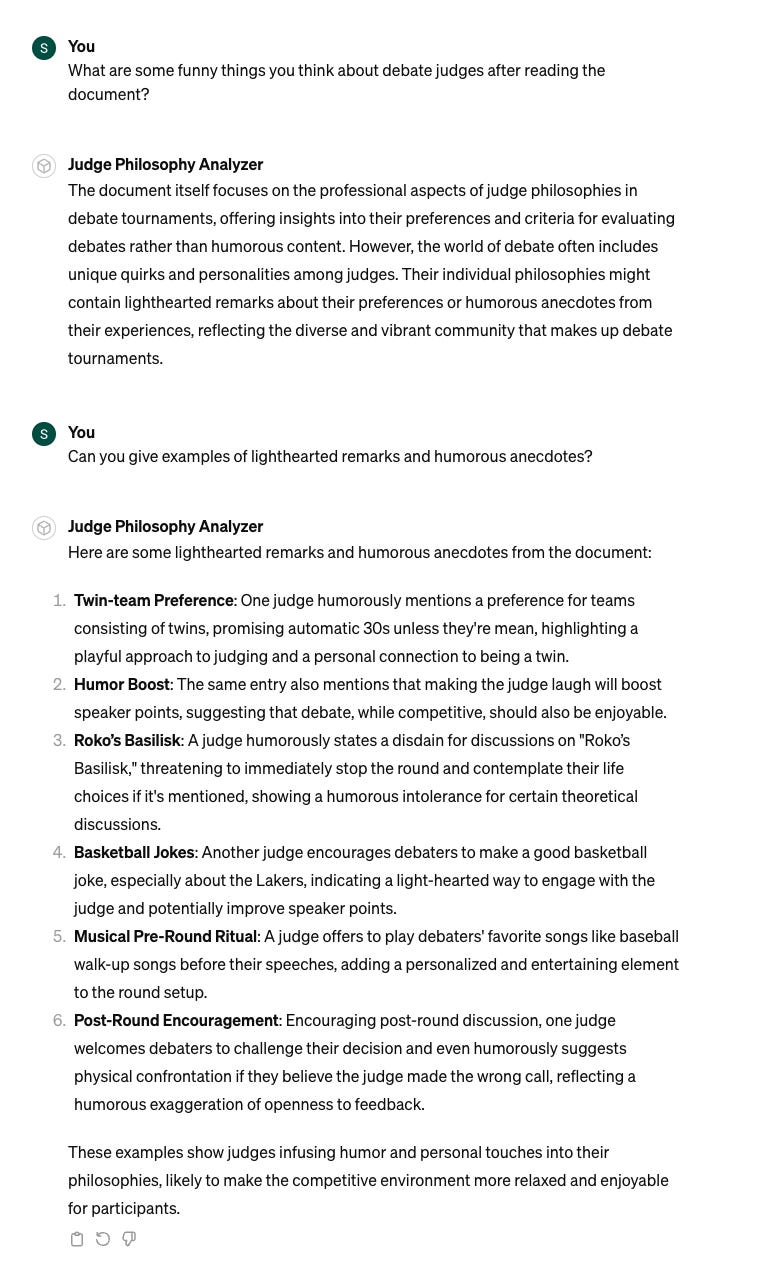

*GPTs/ChatGPT understands humor. AI Godfather Geoff Hinton said he thought ChatGPT understood what it was doing when it started making jokes that couldn’t be found online or explained by “next word” prediction.

I asked it: What are the 5 most ridiculous statements?

These are two that it identified as “ridiculous.”

On Decision Making: "If you believe my decision was wrong punch me in the face". This hyperbolic invitation humorously emphasizes the judge's openness to feedback while also acknowledging the subjective nature of judging debates.

On Speed and Clarity: "Speed is totally fine. I'll be able to flow mostly anything unless you're spreading 3081 paraphrased blips per second". This exaggeration humorously addresses the issue of speed in debate, setting an impossibly high threshold for what constitutes too fast.

There are times when I’m using these AIs that I get a little freaked out; this is one of them.

A bit more on humor —

Knowledge of a field is essential. There is a skills vs. content debate in education. AI pushes things more towards skills (and so do industry “future of jobs” reports), but without knowledge of the area, I wouldn’t have known where to find the “data” and what questions to ask

*Asking the right questions is important. A general prompt to get information about the judges wasn’t very useful. Specific questioning was awesome.

People need to set up the GPTs and engage the GPTs. People need to learn how to set these up and use them. You can have an infinite number of assistants that are very useful for $20month.

These assistants will soon become agents and be even more helpful.

AI can do a lot of very useful stuff quickly. We are going to have to learn how to take ourselves to the next level with AI.

___

The entirety of what is below was produced from simple prompts asking the GPT about what the judges thought of the topics listed.

Common ideas in national circuit judging attitudes based on AI analysis of the judge philosophies of the TOC Gold division

Appearance/Dress

Paraphrasing

Tech over Truth

Frontlining in Second Rebuttal

Disclosure Theory

Properly Extending Arguments

Collapsing Arguments

Progressive arguments

Flowing

Other Important Ideas

Humor

The 5 most ridiculous statements

Appearance/Dress

The document reveals that judges generally do not place a high emphasis on how students dress for debates, suggesting a flexible and inclusive attitude towards dress codes in the debate community. Here are some examples from the document that illustrate judges' views on student attire during debates:

Comfort and Accessibility Over Formality: One judge explicitly states, "I don't care how you dress if you sit, stand, etc. Debate should be comfortable and accessible for you". This statement reflects a broader sentiment that the focus of debate should be on the quality of argumentation and engagement, rather than on appearance or adherence to traditional dress codes.

Equity Considerations: The mention of the tournament having an equity officer suggests an awareness of the importance of inclusivity and accessibility in debate settings. By de-emphasizing the importance of dress, judges signal their support for an environment where all participants can compete on equal footing, regardless of their ability to conform to conventional standards of professional attire.

Focus on Substance Over Style: The lack of concern for how debaters dress underscores a common theme among judges that the substance of what is being debated is far more important than the superficial aspects of how debaters present themselves physically. Judges are more interested in the arguments, evidence, and effectiveness of communication rather than the external presentation.

These examples indicate a progressive approach to debate attire, where the emphasis is placed on making debate an inclusive activity that prioritizes comfort, accessibility, and the quality of discourse over traditional norms related to dress. This approach aligns with broader educational goals of fostering an environment where students can express themselves and engage in debate without being constrained by unnecessary formalities.

Paraphrasing vs Reading Cards

Common positions on paraphrasing among judges, based on the analyzed judge philosophies, highlight a generally negative view towards the practice in debate, with several key points of concern:

Negative Views on Paraphrasing: Judges express strong disapproval of paraphrasing, describing it as detrimental to the quality of debate, educational benefits, and fairness. One judge explicitly states, "The single worst wide-spread practice in PF debate today is paraphrasing" and strongly urges debaters to cut cards instead.

Requirements for Evidence: Despite recognizing that paraphrasing occurs, judges set strict requirements for those who choose to paraphrase. This includes having a cut card or at least a paragraph of the original text ready to be presented upon request. Failure to quickly produce the evidence from which one paraphrases can lead to the argument being disregarded.

Clarity and Full Argumentation: Judges stress that if paraphrasing is used, debaters must ensure they are presenting full arguments, including claims, warrants, and evidence. The practice of spreading taglines and paraphrasing authors to increase speed, without presenting complete arguments, is looked down upon.

Misrepresentation and Penalties: Misrepresenting a card while paraphrasing is considered a serious offense. Judges indicate that such misrepresentation not only discredits the argument but could also result in an automatic loss or significantly lower speaker points.

Speaker Points and Penalties: The judges make it clear that debaters who rely on paraphrasing should not expect high speaker points. One judge mentions a policy of not awarding more than 29 speaker points to someone who paraphrases, reflecting a shift towards stricter penalties for the practice over time.

Encouragement of Direct Quotation and Cut Cards: Judges favor direct quotations and the use of cut cards over paraphrasing. They argue that this approach improves the quality of debate and ensures that evidence is accurately represented.

Ethical and Educational Considerations: The negative view on paraphrasing is also rooted in concerns about ethics and education. Judges believe that cutting cards and presenting evidence directly enhance the educational value of debate and uphold higher ethical standards.

In summary, the common position among judges on paraphrasing is highly critical, with a strong preference for direct quotation and the use of cut cards to ensure clarity, fairness, and the educational integrity of debates. Judges impose strict rules and penalties for paraphrasing, including the possibility of disregarding arguments, lowering speaker points, and even determining round outcomes based on compliance with evidence presentation standards.

Tech Over Truth

It is quite common among judges to express a preference for "tech > truth," indicating they prioritize technical debate skills, strategy, and the execution of arguments over the absolute veracity of those arguments. This stance is based on the view that debate is a competitive activity where the quality of argumentation, evidence handling, and strategic interaction are paramount. Judges who adopt this philosophy are generally open to voting on any well-warranted argument, irrespective of its real-world truth, as long as it is effectively argued and supported within the round. They emphasize the importance of debaters being able to engage with the technical aspects of debate, such as argument structure, evidence comparison, and strategic decision-making.

For example, one judge mentioned, "Tech>Truth – I’ll vote on anything as long as it’s warranted", indicating a willingness to evaluate arguments based on their in-round execution rather than their factual accuracy. Another example is, "Tech over truth within reason - it matters to me that you are making good arguments... Those arguments can be as bizarre as you please so long as you're explaining and warranting things well", highlighting the judge's flexibility in considering arguments as valid as long as they are well-developed and justified, regardless of their alignment with objective truth.

This preference suggests that debaters appearing before such judges should focus on honing their technical debate skills, ensuring their arguments are well-structured, thoroughly warranted, and strategically sound, rather than relying solely on the inherent truthfulness of their claims. However, it's also noted that while technical proficiency is valued, it is not at the expense of making unsubstantiated claims or engaging in unfair debate practices. Judges still expect arguments to be grounded in solid reasoning and evidence, even if the technical aspect of argumentation is prioritized over factual accuracy.

Frontining in Second Rebuttal

Most judges outlined in the document believe that frontlining should start in the second rebuttal. This expectation is reflected in various comments from judges, indicating a preference for proactive engagement with the opponents' arguments early in the debate. For instance, one judge clearly states that the second rebuttal should "frontline everything, no sticky defense", emphasizing the importance of addressing all opposing arguments and not relying on arguments that have not been explicitly countered or addressed. Another judge specifies that "Second Rebuttal must frontline all offense and weighing" and that any offense the debater is going for in the back half must also be frontlined. This indicates a preference for a comprehensive approach to frontlining, covering both the arguments debaters plan to advance and the strategic comparison of impacts.

Additionally, a judge elaborates on the expectation that the second rebuttal should not only address turns but also engage in direct interaction with the arguments, stating that frontlines need to be "directly interactive with the argument you are responding to". This suggests a desire for debaters to not just rebut arguments in a superficial manner but to engage deeply with the substance of the arguments and provide a clear rationale for why the judge should prefer their responses.

Disclosure Theory

Many judges express nuanced views on disclosure theory and caselist disclosure, recognizing the benefits of disclosure for ensuring fairness and enhancing the educational value of debate, while also cautioning against its punitive use.

Judges generally see disclosure as beneficial for debate, as it allows for better preparation and more informed debates. Disclosure is viewed as a practice that levels the playing field, especially for smaller programs that may not have the resources to scout opponents. One judge outlines specific expectations for disclosure, such as disclosing previously read arguments and making good faith efforts to disclose positions, advocacies, and evidence. This judge also expresses a desire for the debate community to move towards practices common in college policy debate, where disclosure norms are well-established.

However, this same judge highlights concerns about misdisclosure and the misuse of disclosure theory to punish debaters for lack of knowledge or unfamiliarity with norms, indicating a nuanced stance that values the intent behind disclosure but criticizes its application as a tool for exclusion or punishment.

Caselist Disclosure

The expectations for caselist disclosure align with those for general disclosure practices, emphasizing transparency and fairness. Judges support disclosing case lists to the extent that it enhances preparation and debate quality, with a preference for accurate and complete citations to prevent misrepresentations.

Judges' Concerns

Despite recognizing the value of disclosure, judges express several concerns:

Punitive Use of Disclosure Theory: Some judges are wary of disclosure theory being used punitively, especially against debaters who may not be familiar with disclosure norms or who come from backgrounds where such practices were not emphasized.

Educational Value and Fairness: While supporting disclosure for its potential to increase the educational value of debate, judges are cautious about approaches to disclosure that might compromise fairness or educational outcomes. They advocate for empathy and clear communication as better strategies for achieving effective disclosure practices.

Properly Extending Arguments

High Threshold for Extensions: One judge states a high threshold for extensions, requiring that all parts of an argument must be clearly extended and explained in later speeches. This includes not just doing impact calculation for its own sake but making analysis truly comparative.

Extensions Must Include Internal Links and Impacts: Another judge emphasizes the need to extend the internal links to the argument as well as the impact, instructing debaters to explain how they get from point A to C before extending the impact. If not done, the judge will still evaluate the argument but be less inclined to vote for it.

Expectation for Comprehensive Argument Extension: Judges expect arguments to be extended comprehensively, including the uniqueness, link, internal link, and impact. A claim without a warrant is not considered an argument, and failure to extend arguments fully can result in a vote against the team that might have otherwise won.

Fewer Well-Developed Arguments Preferred: Judges stress the importance of having fewer, well-developed arguments over numerous undeveloped ones. Teams that collapse and more thoroughly explain their arguments tend to win more often, highlighting the judge's preference for quality over quantity in argumentation.

Weighing and Impact Analysis: The importance of weighing arguments and explaining why one argument is more significant than another is highlighted. Judges look for comparative analysis that guides their decision-making process, emphasizing the strategic value of early and effective weighing in the debate.

Properly Extended Arguments Include Warrant, Link, and Impact: For an argument or turn to be considered for a vote, it must include a full extension of the warrant, link, and impact. Anything presented in the final focus must have been introduced in the summary, and judges discourage introducing new material in the final focus.

Collapsing

Most judges believe that debaters should start collapsing their arguments preferably starting in the second rebuttal. This strategy is emphasized as a way to simplify the debate for both the debaters and the judges, making the round easier to judge by focusing on fewer, stronger arguments rather than trying to cover a broad range of points. For example, one judge explicitly states, "PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE collapse preferably starting in second rebuttal...Pick an argument to go for and weigh that argument". This approach helps debaters to clarify their positions and prioritize their arguments, leading to a more focused and impactful debate.

Judges suggest that by the second rebuttal, debaters should begin to narrow down their arguments, selecting the ones they believe are strongest or most strategic to pursue. This process of collapsing helps to prevent the round from becoming cluttered with too many tags and arguments that lack sufficient warrants or weighing. It's also mentioned that winning a larger number of arguments doesn't necessarily lead to winning the ballot if the arguments are not effectively collapsed and weighed.

In terms of how debaters should collapse their arguments, judges look for a strategic selection of arguments that are directly engaged with the opposition's case, thoroughly warranted, and accompanied by clear impact analysis and weighing. The expectation is that by focusing on fewer arguments, debaters can devote more time to developing these arguments in depth, providing a clearer path to victory for the judges to follow.

These expectations align with the broader educational goals of debate, encouraging debaters to practice strategic thinking, effective communication, and the ability to prioritize arguments based on their strengths and the specific dynamics of the round.

Speed/Taking Quickly

Judges have varied positions on speed in debates, but many express that they are okay with speed as long as it is paired with clarity and does not compromise the quality of the argumentation. Here are some key points reflecting their views and conditions under which debaters can talk fast, supported by examples from the document:

Speed with Clarity: Judges are generally fine with speed as long as the debaters remain clear and understandable. For instance, one judge mentions, "Speed is not a problem... clarity IS the problem, not the speed of spoken word itself". This suggests that as long as judges can follow the arguments being made, they are not opposed to rapid delivery.

Use of Speech Documents: To aid understanding when speaking quickly, judges appreciate when debaters provide speech documents. This helps ensure that even if something is missed auditorily, it can still be reviewed in the document. One judge explicitly states a preference for having a doc to make sure they don't miss anything when flowing, indicating a willingness to accommodate fast speaking as long as there are measures in place to maintain clarity.

Conditions for Speed: Judges specify conditions under which speed is acceptable. For example, slowing down on tag lines, reading plans, and flipping between flows is recommended to aid comprehension while still allowing for speed in other parts of the speech.

Technical Constraints: Judges acknowledge their own limitations in following extremely fast-paced speeches. They advise debaters to give a warning if they plan to speak quickly and remind them that the faster they speak, the less likely the judge is to catch everything on the flow. This emphasizes the balance judges seek between technical debate skills and the practical limitations of comprehension and flowing.

Accessibility and Inclusivity: There's a strong emphasis on keeping debate accessible to all, including those who might not be familiar with or able to follow rapid-fire debate styles. Judges stress the importance of articulation and the potential need for accommodation to ensure that debate remains an inclusive activity. For example, a judge encourages speed only if both teams agree to it and asks for a heads-up to prepare, highlighting a preference for inc

How Should Evidence Be Exchanged?

Judges have clear expectations for evidence exchange in debates, emphasizing efficiency, transparency, and fairness. Here are some key points and examples drawn from their preferences:

Use of Email Chains: Judges strongly prefer the use of email chains for evidence exchange to streamline the process and avoid delays. For instance, one judge mandates setting up an email chain to exchange cases in their entirety before the round starts. This judge explicitly states that untimed evidence exchange will not be tolerated during the debate, and any evidence exchange not part of the email chain will count against the requesting team's prep time.

Efficiency and Timeliness: The expectation is that evidence should be exchanged quickly and efficiently, with one judge specifying that evidence should be pulled up in less than a minute or it will come out of the team's prep time. This underscores the importance judges place on minimizing disruptions and maintaining the flow of the debate.

Transparency and Accessibility: Judges emphasize the need for transparency in evidence exchange. They require that evidence, including cases and any rebuttal evidence, be shared through the email chain to ensure both teams have access to the material being discussed. This practice is seen as crucial for fairness and allows for a more informed and engaged debate.

Handling of Evidence Misrepresentation: Judges are vigilant about evidence misrepresentation, warning that misconstruing evidence could lead to severe penalties, including dropping the team or significantly lowering speaker points. This highlights the emphasis on ethical conduct and integrity in the presentation and use of evidence.

Expectations for Evidence Formatting: Proper citation and highlighting of evidence are expected to indicate what was read during the debate. Judges prefer cut cards with proper citations and discourage poorly formatted evidence or reliance on unformatted links, equating poorly presented evidence with analytics in terms of credibility.

What are the Most Important Issues for Lay or Inexperience Judges

Clarity and Pace: Lay judges often prefer debaters to speak at a conversational pace to ensure clarity and understanding. They emphasize the importance of being understood over speed, suggesting a preference for clear articulation and avoid using jargon that may not be familiar to them.

Argument Convincingness: Lay judges decide rounds based on how convincing the arguments are rather than technical aspects of debate. They stress the need for arguments to be fully warranted and extended in the final focus, indicating a preference for quality over quantity in argumentation.

Respectful Engagement: A common expectation is for debaters to treat each other with respect. This includes being polite in cross-examinations and maintaining a professional demeanor throughout the debate. Lay judges often have zero tolerance for offensive or rude behavior.

Use of Evidence: While lay judges may not emphasize speed or technical debate strategies, they value strong evidence and clear links between arguments and impacts. They prefer arguments supported by good evidence and clear logical reasoning.

Engagement with Cross-Examination: Good responses during cross-examination are noted as important. Lay judges appreciate debaters who can effectively engage with their opponents' questions and provide clear, concise answers.

Avoidance of Debate Jargon and Theory: Lay judges often recommend staying away from dense debate terminology and theory arguments. They prefer debates that are accessible to those without extensive debate experience.

Weighing and Impact Analysis: Clear and concise weighing of arguments is crucial for lay judges. They look for debaters to explain why their case or impacts are more significant, helping them to decide the round based on the presented arguments.

Adherence to Norms of Civility: Emphasizing the educational aspect of debate, lay judges expect all participants to engage in a manner that is civil and conducive to a productive exchange of ideas. Aggressiveness and disrespect can negatively impact speaker points.

Focus on Substance Over Style: While delivery is important, lay judges primarily focus on the substance of the arguments. They appreciate debaters who can simplify complex issues and present their cases in an understandable and compelling manner.

Openness to Progressive Arguments: Some lay judges express openness to progressive arguments as long as they are presented clearly and the debaters can make a strong case for their relevance and impact within the round.

How Do judges approach more progressive arguments in debate?

Judges' approaches to socially progressive arguments in debates are generally supportive but with several caveats aimed at maintaining the educational and competitive integrity of the activity. Here are some highlighted expectations and concerns:

Support for Progressive Arguments: Judges express openness to socially progressive arguments, including discussions on various -isms (racism, sexism, ableism, etc.), as they can add depth and relevance to debates. However, they stress the importance of handling these topics with sensitivity and awareness, ensuring that debaters do not marginalize or "otherize" groups, especially if they do not personally belong to the groups they are discussing.

Conditions for Socially Progressive Arguments: Judges encourage debaters to engage in socially progressive arguments, but with conditions. For example, if discussing sensitive topics such as sexual harassment, assault, or suicide, they expect a trigger warning to be provided before the round. This consideration underscores the importance of creating a safe and inclusive environment for all participants.

Accountability and Reasonability: The accountability of advocacy through mechanisms like crossfire and flex prep is emphasized, with a default to reasonability. Judges want debaters to be prepared to defend their advocacies and ensure they contribute positively to the debate space.

Concerns Over Quality and Frivolity: While receptive to progressive arguments, judges express concerns about their quality and the potential negative impact of poorly constructed arguments on the activity. They discourage frivolous theory and tricks, indicating a preference for arguments that genuinely aim to improve the debate space and consider the long-term implications for participants.

Educational Value and Transformation: Judges believe in the transformative and educational value of debate, including the use of progressive arguments. However, they caution against arguments that may deem the activity itself as inherently bad or unworthy of engagement, suggesting that critiques should be constructive and aimed at improving the community.

Specific Guidance on Socially Progressive Arguments: Judges provide specific guidance on how to engage with socially progressive arguments, such as avoiding otherizing, providing trigger warnings for sensitive topics, and ensuring arguments are made in good faith with an eye toward improving the debate community for current and future participants.

How Important is Flowing to Judges?

Flowing, or taking detailed notes during a debate, is considered crucial by most judges for accurately following and evaluating the arguments presented. Judges' philosophies indicate that they rely heavily on their flow to track the development of arguments, note which points have been responded to or dropped, and make their final decision based on the structure and progression of the debate as captured in their notes.

Importance of Flowing for Decision Making: One judge emphasizes that they will look down at their flow at the end of the round to make decisions, including evaluating framing, the clash of arguments, and weighing. This process involves considering each argument's internal links and uniqueness, and only considering offense and responses that are extended and implicated in the final speeches.

Flowing as a Skill: Judges appreciate debaters who can flow accurately themselves, noting that this skill is essential for tracking the round and ensuring that responses are directly engaging with the opponents' arguments. The ability to flow effectively is often tied to a debater's ability to perform well, as it impacts their ability to respond to and extend arguments throughout the debate.

Expectations for Clarity and Structure: Judges expect debaters to be clear and structured in their speeches to aid in flowing. This includes signposting, or clearly indicating the structure of speeches and where the debater is in their case or rebuttal, to make it easier for judges to follow along and accurately record arguments on their flow.

Flowing and Speed: While some judges are comfortable with speed, they often note that clarity is paramount. Judges mention that they will only flow what they can comprehend, indicating that debaters must balance speed with clear articulation to ensure their arguments are recorded accurately on the judge's flow.

Adaptation to Judges' Flowing Preferences: Judges appreciate when debaters adapt their speaking style to the judge's ability to flow, such as slowing down on tag lines or crucial arguments to ensure these points are captured accurately. This adaptability is viewed as a strategic skill that can influence the judge's understanding and evaluation of the round.

Flowing and Argument Extension: Judges rely on their flow to track argument extensions through the round. They expect debaters to extend arguments in a way that is clear and traceable on the flow, emphasizing the importance of continuity and clear reference to arguments made in previous speeches.

Other Important Ideas I haven’t specifically asked about?

The document covers a wide array of topics relevant to debate judging philosophies, beyond the specific questions asked. Here are additional main ideas extracted from the analysis of judges' philosophies that haven't been directly addressed in previous inquiries:

Framework and Interpretation: Judges often discuss their views on how debates should be framed, including the importance of engaging with the affirmative's arguments and how to approach non-traditional formats. They highlight the enjoyment and challenge of listening to framework debates, provided they are well-developed.

Judging Philosophy and Bias: Some judges elaborate on their overall philosophy towards judging, emphasizing impartiality and an open-minded approach to evaluating arguments. They stress the importance of not allowing personal biases or preconceived notions to influence their decisions.

Evidence and Argumentation Standards: There is a strong focus on the quality of evidence and argumentation, with judges specifying their expectations for clarity, substantiation, and logical structuring of arguments. They emphasize the necessity of claims, warrants, and impacts for an argument to be considered valid.

Engagement with Progressive Argumentation: Judges provide insights into how they view and evaluate progressive arguments, including kritiks and theory arguments. They express openness to these types of arguments but also highlight the need for clear warranting and specific engagement with the topic at hand.

Role of the Judge and Decision-making Criteria: Many judges discuss their role in the debate, highlighting the importance of minimal intervention and basing decisions on the debaters' ability to clearly communicate and persuade. They advocate for debaters to provide clear frameworks or standards to guide the judge's decision.

Adaptation to Different Styles and Formats: Judges acknowledge their own limitations and learning curves, especially when evaluating debates involving complex theories or kritiks. They appreciate debaters who can adapt their arguments and delivery to make them accessible and understandable.

Importance of Ethical Conduct and Fairness: Judges emphasize the significance of ethical conduct in debate, including honesty in evidence presentation and respect towards opponents. They discuss the implications of evidence misrepresentation and the importance of maintaining a fair and respectful debate environment.

These additional main ideas showcase the complexity and diversity of judges' philosophies, reflecting a broad spectrum of expectations and preferences that debaters need to navigate. From technical proficiency and evidence quality to ethical considerations and the ability to engage with progressive arguments, these themes underscore the multifaceted nature of competitive debate and the varied criteria judges use to evaluate performances.

Are there any interesting or funny sentences in this document?

"If you run ‘dadaism’ or ‘linguistics’ I will be upset that you have made me listen to that for 45 minutes and I’ll be extra receptive to reasons why progressive arguments are bad for the debate space; you will definitely not get fantastic speaks even if I begrudgingly vote for you because you won the round". This quote humorously expresses frustration with certain argument choices while also hinting at the judge's openness to being convinced otherwise.

"Trix are for kids. If I hear the words “Roko’s Basilisk” I will literally stop the round and submit my ballot right there so I can walk away and think about the life choices that have led me here". This amusingly dramatic statement showcases the judge's disdain for certain types of arguments, likening them to children's cereal and existential contemplation.

"Speaks are fake you’ll all get good ones". A light-hearted take on speaker points, suggesting a generous approach to scoring while playfully questioning the objectivity of the metric.

"Being forced to respond in second constructive is stupid. If your opponents say you do just respond with 'lol no I don’t' and you’re good". This offers a humorously simplistic strategy for dealing with certain debate requirements, poking fun at the formality of structured responses.

"I WILL NOT VOTE FOR EXTINCTION FRAMING AS PREFIAT OFFENSE". The capitalization adds a comedic emphasis to the judge's firm stance on a specific argument strategy, highlighting the idiosyncrasies of debate preferences.

What are the 5 Most ridiculous statements?

On Time Management and Evidence: "I will be personally timing rounds since plenty of varsity level debaters no longer know how clocks work". This statement humorously addresses a concern about debaters' time management skills and immediately sets a strict standard regarding speech timings.

On Argument Extension in Final Focus: "Defense is not 'sticky.' If you want something to count in the round it needs to be included in your team’s prior speech. The idea that a first speaking team can go 'Ah hah! You forgot about our trap card' in the final focus after not extending it in summary is ridiculous and makes a joke out of the event". This remark humorously criticizes a specific debate tactic, comparing it to playing a "trap card" in a game, highlighting the importance of properly extending arguments throughout the debate.

On Theory Arguments: "Asking me to close my eyes and just check the box after essentially saying 'yadda yadda nuclear winter' is as ridiculous as doing the opposite after hearing 'MAD checks' with no explanation". This statement humorously critiques debaters' reliance on theory arguments without proper explanation or engagement, emphasizing the need for substantiated argumentation.

On Speed and Clarity: "Speed is totally fine. I'll be able to flow mostly anything unless you're spreading 3081 paraphrased blips per second". This exaggeration humorously addresses the issue of speed in debate, setting an impossibly high threshold for what constitutes too fast.

On Decision Making: "If you believe my decision was wrong punch me in the face". This hyperbolic invitation humorously emphasizes the judge's openness to feedback while also acknowledging the subjective nature of judging debates.

These examples reflect the diversity of personalities and perspectives among debate judges, demonstrating a range of attitudes from the strict enforcement of rules to a more humorous and relaxed approach to engaging with debaters.

A little more on the humor…