Education's Quiet Surrender to AGI

Yesterday I read a powerful post by Armada Shehu, VP of AI at George Mason — Beyond the AGI Spectacle: What We Are Actually Living Through.

In it, she starts by pointing out that AGI isn’t going to be a moment (something I think everyone or nearly everyone agrees with), but that rather through a series of innovations and societal absorptions.

Here’s what I suspect: we will not recognize AGI as it arrives. We will recognize it only in retrospect…There will be no headline announcing “AGI Achieved.” There will be no moment when everyone agrees the machines have crossed some threshold. Instead, months or years from now, we will look back and realize the boundary was already crossed. Not through a single system achieving general intelligence, but through the cumulative handover of decision-making authority to systems whose reasoning we can no longer fully trace, verify, or override…

The fundamental problem is that we cannot absorb it quickly enough (or that we do not try).

So, when I hear the word “AGI,” I do not immediately think about consciousness or takeover. I think about absorption capacity.

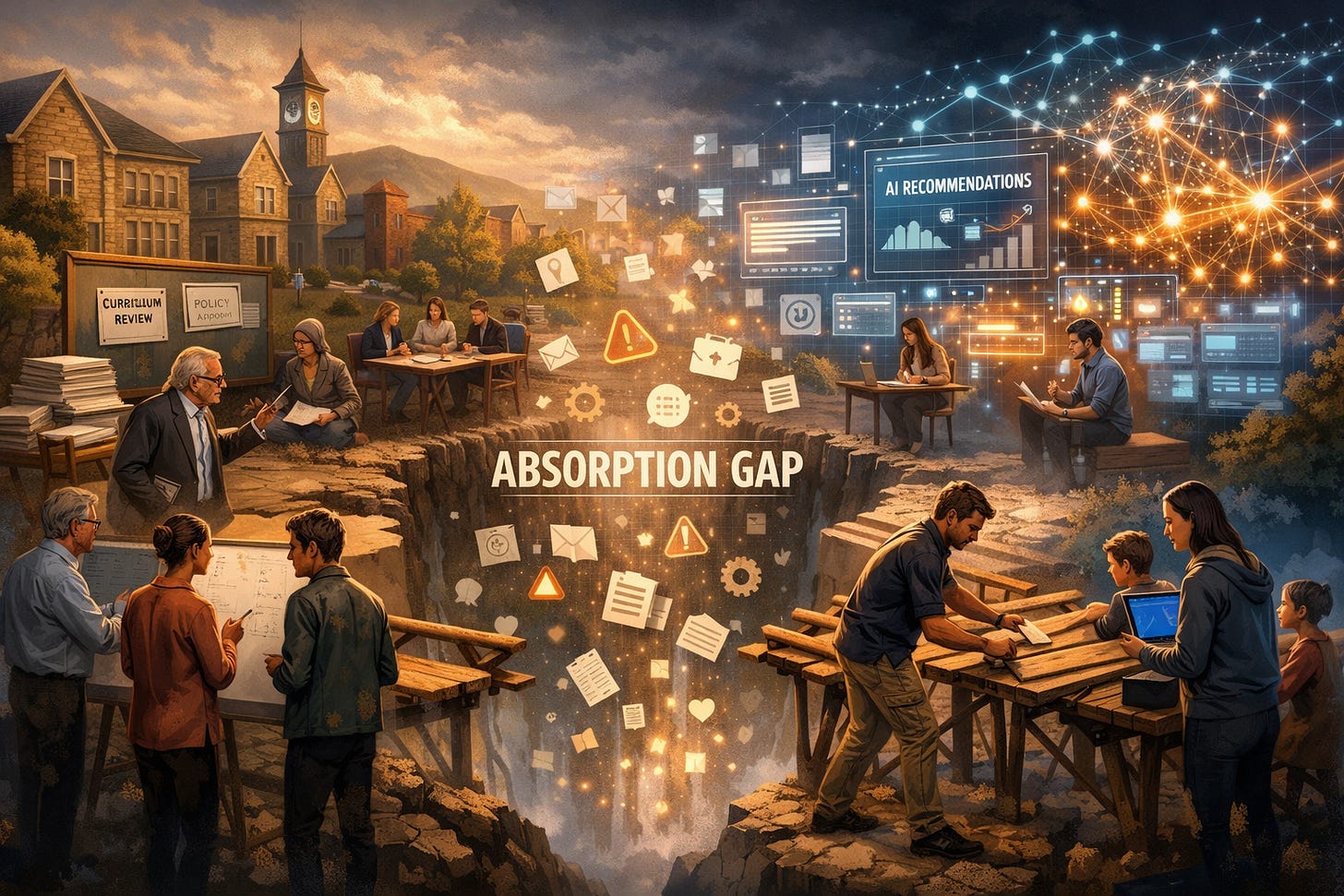

By absorption capacity I mean the rate at which human systems can integrate new AI capabilities, adapt their practices, update their governance, and still maintain meaningful oversight. That rate is not fixed. It varies across institutions, sectors, and countries. It is also, in many places, completely out of sync with the pace at which AI is evolving.

At a large public university, I see this misalignment every day. AI models iterate on timescales of weeks. Vendor platforms push new “smart” features overnight. Meanwhile, curriculum revision takes years. Policy changes require committees, consultation, and approvals. Budget cycles are annual. Regulations move even more slowly.

The result is a growing gap between the systems we are actually using and the governance that is supposed to make sense of them. That gap is what I call the absorption gap. It is not a theoretical construct. It is a widening space where AI is already part of the decision infrastructure, while our ability to verify and steer its behavior falls behind.

Since we cannot absorb it properly (many are not even trying), we lose control.

We started with pilots meant to support human work. AI tools to help students digest readings. AI tutors that were always available. AI assistants that helped faculty design syllabi compliant with institutional, state, and federal regulations. Systems that helped staff draft and summarize memos, freeing time for work that requires human judgment.

These were framed as aids. They fit a familiar story: humans in charge, machines supporting.

Then something subtle began to change. The systems started to do more than support. They started to recommend, route, and prioritize. Delegation crept in. Scheduling assistants that not only propose but confirm times. Systems that flag which tasks deserve attention and which can wait. Recommendation engines that tell students which resources to focus on. In some institutions, systems that weigh in on admissions decisions, a trend I view with real concern.

The line between suggestion and decision does not move all at once. It shifts in small steps. A human accepts one automated recommendation, then another, then hundreds of them. The cumulative effect is a slow handover of micro-decisions to systems whose inner workings we cannot fully audit. This is the augmentation-to-autonomy continuum.

In the context of education, she shares

I see teachers who have been told alternately to ban AI, ignore AI, or use AI without clear guidance or support.

My daughter’s public school system recently signed contracts with Google to provide AI tools, but no meaningful teacher training accompanied the rollout. The result is confusion at the classroom level. Some teachers conflate all AI, collapsing generative AI and basic machine learning (ML) into a single threatening category. I’ve watched teachers refuse to allow students to use simple ML techniques to enhance science projects, threatening disciplinary action for what they perceive as “cheating,” when the students are actually engaging in legitimate computational work.

Thirty minutes away, students at well-resourced private schools are taking courses on prompt engineering and AI-assisted research.

This is capability inequality in practice. Not everyone at different speeds, but different populations solving completely different problems while the same technology reshapes the landscape under all of them. In one setting, students are learning to work with AI as an instrument. In another, they’re learning that AI is something to fear and avoid, or encountering it through top-down contracts without the pedagogical infrastructure to make sense of it.

*I also see my own children in middle and high school, moving through curricula that look almost unchanged,* while the technology around them evolves rapidly. *The gap between what they are learning and the world they are entering grows wider every semester.*

Failure to engage AI and learn how to use it sets the stage for massive inequality.

Another asymmetry that deserves more attention is capability inequality. AI is not a natural equalizer. It amplifies existing advantage.

Individuals with strong skills and clear goals use AI to multiply their productivity. Organizations with good data infrastructures and agile management integrate AI and pull away from competitors. Regions with strong educational systems and compute access accelerate. Others stall.

Every gain in AI capability risks widening the distance between those who can absorb it and those who cannot. Students with access to AI literacy, guided practice, and safe sandboxes learn to use these tools as instruments. Students without such access encounter AI primarily as hype, fear, or outright prohibition. Workers in AI-ready organizations learn to work alongside these systems. Workers elsewhere watch opportunities consolidate away from them.

The cascade is uneven by sector and geography. Finance will adopt faster than K–12 education. Urban centers will adapt faster than rural communities. Well-funded institutions will outpace under-resourced ones. This is not a future scenario. It is happening now.

The most urgent investment today is not in ever-larger models, but in AI-ready institutions and communities.

This requires proactive efforts.

I don’t have good answers. What I do know is that governance can’t be separated from literacy. People can’t contest what they don’t understand. They can’t exercise agency over systems that are illegible to them. So any governance that works has to include serious, scaled investment in public understanding. Think less coding bootcamps and more deep engagement with what these systems can and cannot do, where their authority should and shouldn’t extend…This costs money and time that most institutions don’t have. Which means we’re building governance on a foundation that doesn’t exist yet.

This also requires real investment in AI literacy at scale: K–12, higher education, workforce training, and public-facing programs. Literacy is not about turning everyone into a coder. It is about enabling people to understand enough to have informed preferences, to contest decisions, and to exercise agency…

The ethical frontier is not to make machines superintelligent. It is to make societies super-responsible. The measure of our success will not be how intelligent our machines become, but whether we become super-responsible: capable of absorbing, steering, and co-evolving with what we’ve built.

When I follow what the leaders in this emerging AI world are saying, I don’t see that much disagreement

*AGI and ASI will not arrive as moments

*Time-frames are uncertain (generally 2026-2035 for most)

*”We” (civil society) is largely not ready for the unfolding disruption

*We need to do more to improve our odds of minimizing inequality and social unrest

Over the last few days, I’ve come across a few podcasts that serve to extend a lot of what has been said here —

Ben Goertzel

(1) AGI likely between 2026 and 2035

(2) The status quo will generate enormous inequality if we do not act

(3) UBI will be a useful stop gap, but to really minimize inequality, we need widely distributed AGI systems that all individuals can take advantage of.

Here references Emad Mostaque’s powerful work — The Last Economy

Demis Hassabis

*AGI 2030, multimodal reasoning now

*The industrial revolution and all the changes it introduced 100 years. Something similar with AI will happen, but it will take 10 years.

Shane Legg

*50-50 chance of minimal AGI by 2028; full AGI by the early 2030s.

*We need to manage the societal disruption

__

It is true that most of us do not get a vote on whether major tech companies build AGI. That train is moving, with or without our approval. But that does not mean we are powerless. Agency does not disappear just because the biggest decisions are made elsewhere. It shifts. The real question is not “Can I stop AGI?” but “Where can my choices still bend the path?” In education especially, individual decisions compound fast. AI vice presidents and senior leaders at universities can redirect billions of dollars, set research priorities, and determine whether AI is treated as a narrow technical tool or as a civilizational shift that reshapes every discipline. One provost signing off on an AI center, or one dean insisting AI literacy belong in general education, can quietly change the trajectory of an entire institution.

That same leverage exists further down the chain. Individual professors and department chairs decide what counts as legitimate knowledge, what skills get assessed, and what students practice every day. Teachers can launch AI courses, embed AI into existing classes, or simply create spaces where students are allowed to wrestle seriously with what intelligent machines mean for work, ethics, and power. Debate coaches, in particular, sit at a powerful intersection. By supporting AI topics, encouraging students to research AGI timelines, risks, and benefits, and helping them argue both sides rigorously, they turn AI from a buzzword into something students actually understand.

Leaders of organizations, especially educational organizations and community nonprofits, have another kind of agency that often gets overlooked. They can decide what their organization stands for in an AI-shaped world. A nonprofit director can choose to run AI literacy workshops for families, partner with local schools, or create safe, guided spaces for young people to experiment with AI rather than fear it. Educational leaders can convene cross-sector conversations, bring in outside experts, and align funding around long-term capacity instead of short-term tools. Even small organizations can act as hubs, translating complex AI issues into language communities trust. What can you do in your role? You can propose a course, start a reading group, design a unit, push for a new topic, or launch a pilot program. You may not control whether AGI is built, but you absolutely have a say in how prepared people as it arrives.