Debating Jobs: Artificial Intelligence, Upcoming Unemployment and the Impact on Schools

Updated 6-25-23

TLDR

It's likely that AI will result in a significant increase in at least temporary unemployment.

Upskilling will depend on proactive measures taken by governments and schools to help people prepare to live and work in an AI world; this includes aggressive integration of AIs into the educational system. It’s an (international) emergency.

Government assistance programs will likely be needed but may not come and will only solve a small part of the problem.

Governments and schools must help individuals manage the psychological fallout of the transition and include teaching AI literacy.

Introduction

There is a polarized debate over what the rapid development of AI means for jobs, with some arguing that it will result in 80% of workers being unemployed and others arguing that it will have little to no impact at all, simply eliminating “drudge work” that no one wants to do in the first place while creating a new renaissance of jobs that everyone will love.

In this post, I’ll explore the parameters of the debate and what it means for schools and educators going forward. As you will see, even in the best of circumstances, schools will need to adapt quickly and in essential ways.

The Jobs Wipe Out Argument

The ‘jobs wipe out’ claim is based on a simple argument: “AIs” will be able to do a lot of the jobs people currently do, and since it costs companies less to employ AIs (and they don’t file HR complaints) than people, they will replace the people with AIs..

As Sam Altman was quoted in my last post, as the world gets closer to AGI and ASI (which may only be ten years away), these AIs will be able to do more and more of what we can do, even becoming doctors. But between now and then, however long that takes, lots of jobs could be lost.

Although he’s an outlier, Ben Goertzel makes an extreme argument regarding jobs:

Others –

Goldman Sachs

If generative AI delivers on its promised capabilities, the labor market could face significant disruption. Using data on occupational tasks in both the US and Europe, we find that roughly two-thirds of current jobs are exposed to some degree of AI automation, and that generative AI could substitute up to one-fourth of current work Extrapolating our estimates globally suggests that generative AI could expose the equivalent of 300 million full-time jobs to automation. (Goldman Sachs, March 2023)

OpenAI

Our findings reveal that around 80% of the U.S. workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of workers may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted. We do not make predictions about the development or adoption timeline of such LLMs. The projected effects span all wage levels, with higher-income jobs potentially facing greater exposure to LLM capabilities and LLM-powered software. Significantly, these impacts are not restricted to industries with higher recent productivity growth. " "Our analysis suggests that, with access to an LLM, about 15% of all worker tasks in the US could be completed significantly faster at the same level of quality. When incorporating software and tooling built on top of LLMs, this share increases to between 47 and 56% of all tasks.* (OpenAI)

This isn’t mere speculation; we are already starting to see layoffs.

John, GATO Project, May 21, 2023

The tech industry has just undergone a wave of layoffs that were largely attributed to other market forces but are now undergoing yet another wave of layoffs, and most companies are flat-out saying we're automating these jobs. And that means those jobs aren't coming back. I think there will be some job creation, but I don't disagree with Ansel and John either. I think the amount of offset is going to be very difficult, partially because one of the things these systems do so well is empower one person to work as multiple people.

And these jobs won't just be lost in the United States; they'll also be lost in developing countries like India and China, where developed nations have started outsourcing business functions, such as call centers. A call center is something that can easily be replaced with a bot, saving companies billions but leaving millions of people in the developing world unemployed.

Mo Gadwat argues that in the next 2-7 years that millions of jobs will be lost.

The Jobs Cornucopia Argument

The contention that there will be many job opportunities in an AI world is founded on three premises.

Productivity and demand both play a role. There seems to be a general agreement that the integration of AI will make workers more productive, which means they will be able to accomplish more in the time they have available. This AI-fueled productivity boom will create economic growth, even if unemployment increases (Goldman Sachs). The argument being made here is that if growth and productivity continue to increase, then demand in the economy will also increase, which will eventually lead to more jobs being available for people to fill.

Humans are responsible for the creation of jobs. In the 1850s, more than 80 percent of the people living in the United States were employed in some form of agricultural labor, according to historical records. Today, less than 3% of the population engages in this practice but they are employed.. Other professions have come into existence as a direct result of human innovation that simply did not exist in the 1850s. These professions include those of airline pilots and stewards, Uber drivers, rocket scientists, and system administrators. I could continue on in this vein. The reality is that we have used technological progress to invent entirely new careers.

These jobs are going to be more satisfying. Although I've never had the opportunity, I can only imagine how difficult it must have been to cultivate and harvest crops in the scorching heat. Even driving an Uber in an air-conditioned vehicle is much better than that. So, there is this corollary argument that the new jobs will be better and more fulfilling.

The world is getting better. A common argument made in defense of economic growth and capitalism is that the world is getting better. Recently (May 13), Sam Altman pointed to evidence that global poverty has declined over the last three decades. Though that obviously isn’t specific to AI, since AI is a “technology,” and technology has improved society, perhaps this technology will advance society as well.

The slow transition. There is an argument that the transition from the old jobs to the new jobs will be gradual and therefore that the disruption will be minimal. The slow transition argument doesn’t contend that today’s technology is not radical, but that it will take industry awhile to absorb it (industry is conservative, they say), minimizing the disruption (Lecun).

Yann LeCun, Chief Data Scientist at Meta, professor at NYU, and winner of the Turing Prize for his work in AI, adopts this cornucopia position, even claiming that “every economist” he’s spoken with believes this and that we should trust the economists.

No economist believes we're going to run out of jobs because no economist believes that we're going to run out of problems to solve, or requirements for human creativity and human communication and stuff like that. So this is going to create as many jobs as it makes disappear.

A Few Problems With the Cornucopia Argument

You may be thinking the cornucopia argument is strong, and maybe it is, but has a number of limitations.

Non-Human workers. As you can see in the chart below, previous technological advances led to new industries that required humans.

Today, we are looking at at least many new industries that do not require humans at all.

Sam Altman in Madrid (May 23):

If you were to start a business, why would you start one that requires (a lot of) employees? Why would you want high labor costs and liability risks created by people? Why would you want to deal with all the drama your employees create? Why would you want to deal with labor laws? Why would investors want any of this?

Eventually, maybe there will be more humans needed in future jobs, and maybe at least one third of humans will run their own businesses, but in the interim, it appears those jobs are declining.

A quick transition. Not everyone agrees the transition from old jobs to new jobs will be gradual. Emad Mostaque, the CEO of Stability.ai, argues that industry will be significantly impacted next year and education will be significantly impacted in year three. Sam Altman adds (May 16): “We always find new jobs and we adapt but I don't think we've ever had to contend with one that will be as fast as we'll have to contend with this one. And that's going to be challenging.” In an interview in Korea in early June, he explained that it usually takes two generations to adapt to changes in technology and that AI will be producing massive disruptions within 10 years. This doesn’t mean we will never adapt, but there is obviously a risk of significant transitional unemployment.

On June 7th, Sandhini Agarwal, a Policy Researcher at OpenAI, explained:

I think the economic displacement question (is my biggest fear). For example, with the Industrial Revolution, when that happened long term, it was great for the world, great for society, a lot of progress. But the immediate 50 years after the aftermath, were really painful. So I think that's what we need to figure out. How do we manage this transition? How do we make it least painful for society? I think in order to do that, there's a lot of work that like governments people have cut out for themselves. So I think that's what I'd say in the now is one of my biggest fears in worrying.

Net loss. Many argue there will be a net-loss of job, even if new jobs are created.

Hansel from the GATO project on May 23

Sure, it'll create new jobs, but it's not going to be anywhere near enough one to replace the jobs that it's going to displace. And especially it's not going to create new ones and that much of a short time. We're seeing huge disruptions in the next five years and that's being incredibly optimistic. And that's not a myth that is guaranteed. The real question is, what are the fundamental shifts that are going to happen and how are we going to address them because Congress is still thinking in the old model, right? Where you still need humans working eight hours a day, five hours, sorry, five days a week, and just just just grind right? AI is gonna automate a lot of that grind. And we're not going to find enough what's the word? Busy work to keep ourselves busy right? We should we should focus more on liberating that time for humans do better things right.

Transitional support will be hard to come by. At a recent hearing, Senators demonstrated a lot of knowledge of key issues related to AI, but that doesn’t mean there is support for programs such as universal basic income (UBI) that people like Sam Altman and Andrew Yang argue will be necessary to support the transition. As of today (May 23), the US is deadlocked on raising the debt ceiling to pay for programs that it has already agreed to fund. And the US debt is high ($34 trillion), so there is a reasonable debate about whether or not we should increase government spending to pay for programs such as UBI.

Moreover, this previous discussion was just about the United States. Even if the US did institute a universal basic income, where would developing countries get the resources to fund a UBI? As it is, they are struggling with extensive poverty now, many are already heavily indebted to China and western banks, and they just do not have money to fund such a program. This will just leave more people in their countries unemployed and without a safety net.

UBI is only a minimal solution. Sam Altman has proposed a UBI of $1300/month and Andrew Yang has proposed a UBI of $1,000/month. That may help prevent extreme poverty, but if I lost my job and only had $1300/month to live on, I’d struggle to support my kids. At a minimum, they’d have to withdraw from college and change schools. I supposed I would now qualify for a lot of financial aid, but how could these schools provide such financial aid when students start withdrawing and can no longer pay tuition? Of course, then the unemployment problem snowballs.

And even if it solves extreme poverty, it’s not going to reduce the radical inequality that will emerge. Who is going to be happy with a world where someone has a company with $1 billion in revenue and three employees and 10,000 people live on $1300/month? The gini coefficient, which measures the rich-poor gap, is a strong predictor of societal conflict, and we may be headed toward a world of heightened inequality and conflict between the haves and the have nots.

Even in the US, conditions for that have been present since at least the 2016 election cycle.

Regardless, even Yann Lecun argues societal change must be be intentionally led:

But every technological revolution, unless it's accompanied by sort of, you know, political changes, and social changes, generally, profit, a small number of people, at least temporarily, right, that happened in the Industrial Revolution in the late 19th century, where, you know, a few people became extremely rich, and a lot of people were exploited. And then, you know, society changed and they were like, social programmes and, and, you know, income tax and, and high tax for richer people and stuff like that, which the the US as backpedaled on this, but not Europe, or the UK to some extent to but not not the rest of Europe. So there is a question of, you know, how you distribute the wealth if you want, okay, how do you organize society so everyone profits from it? But that's a political question.

Education is not ready. I’ve spent the last 6 months pushing educators to come around on the importance of training students to use AIs and changing their curriculums to be relevant in the AI world.

Some are slowly starting to come along. I’ve had some incredible conversations with private school leaders in the UK, Mexico, Vietnam, and the Middle East and had the opportunity to present at the Cottesmore Education Conference. On June 14, the Cottesmore School announced a new position: “Head of AI.” I believe this is the first position of this nature at the K-12 level.

The New York City Department of Education has finally changed its tune. but he use of technology is still prohibited in many K–12 schools, and even aggressive plans are quite slow, with some schools starting to think about professional development for teachers in August or September of 2023.

In the fall of 2023, there will at best be some sporadic usage, but most schools still have no idea how to use this technology, even if they want to use it. Many of the most creative educators are attempting to use it to teach students the same subjects and abilities that computers are best at (like raising SAT scores). Do really hope your child can grow up to do something (almost) as well as a robot?

A much more extensive strategy is required. Sam Altman in Madrid (May 23):

Although it's possible that the robots will teach the students what they need to know to succeed in an AI world, it doesn't seem as though their K–12 education will adequately prepare most of them for this AI world. And even where education is willing, the resources may not always be available, particularly in developing countries, to simply retrain all of these workers.

And we do not know what jobs we need to train people for: “Prof LeCun told the BBC: "This is not going to put a lot of people out of work permanently." But work would change because we have "no idea" what the most prominent jobs will be 20 years from now, he said.” [The Guardian]

Quality and relevant education in an AI world is essential to supporting this transition. LeCun claims that Stanford economist Erik Brynjolfsson, who has investigated how technology affects labor markets, supports his assertion that, in the long run, everything will work out with jobs.

Erik Brynjolfsson claims that AI might just be used to automate our daily tasks, which could cause a significant unemployment problem. He even claims that in order to stop automation and place more emphasis on augmentation, proactive measures are needed. And it's probably reasonable to assume that changes in the educational system will be required to support this augmentation. However, if we just assume that everything will be okay without taking any action to make sure it is, then it won't. Brynjlfsson's argument can be found in detail here.

It's not as easy as it sounds to upgrade your skills. It will be challenging to make the switch from bookkeeping to running one's own AI services business.

The global poverty reduction is not great. The use of technology has significantly contributed to a decline in global poverty, but almost all of this improvement has taken place in just two countries: China (mostly) and India. What does this mean?

To begin, what this implies is that proactive government policies are required in order to fully capitalize on the benefits of technological change.

Second, it indicates that the majority of people will not be able to take advantage of the benefits brought about by technological change; we’ve had amazing technology for at least the last 70 years and poverty remains rampant in most of the world. If we are serious about applying the lessons learned from previous "technological" revolutions, then we should also apply them to this one. It’s not going to happen on its own.

Third, it means that things don’t just work out. Yes, sometimes things work out with a lot of intentional effort, but it obviously always does not (see most of the world).

I'm not saying that all of this proves the cornucopia argument is incorrect, but it does have many flaws, and even if it is true, it is likely that unemployment will rise in the near future. The only argument against a massive short-term disruption is that the transition might be slow (LeCun), but even if that is true, workers need to be retrained and new government policies need to be adopted. Education needs to train students for the future, not the past. Even the greatest technoptimist of our time, LeCun, believes this.

Risk Analysis

After considering the pro and con arguments, I’m going to attempt some risk analysis.

Anxiety 100%. It is possible that a lot of jobs may be lost and this possibility creates fear and anxiety. Fear and anxiety are inevitable.

Loss 100%. There is a 100% chance of job loss. Job loss from AI is happening and everyone agrees it will. The only debate is how much time we have to adapt and how many new jobs will be created. Will those new jobs be enough to offset the losses and will those who gain share their prosperity with those who lose (the global record on the latter is not so good).

50% risk job loss. At best, there is probably a 50% risk of massive job loss in at least the interim. Do you disagree with 50% chances? What percentage chance do you place on it? Why?

Doing nothing is silly. We need to prepare for the future. If we don’t, we won’t be prepared to live in it. Educators tell that to students every day. Imagine what might have happened if the US hadn’t prepared to deter a Russian nuclear first strike simply because it hadn’t happened yet. Should Poland not strengthen its defense even though the Russians haven’t yet invaded and may never invade?

The Impact on Schools

What kind of implications does this have for schools?

My opinion is that this will, in a variety of different ways, have an impact on the educational system.

Disengaged students. Some students will worry that no matter what they study, they will not be able to secure employment in the future. Others will be concerned that the skills and content they are learning in school will not prepare them for employment opportunities in the future. These are both valid concerns that should be addressed. It's possible that both of them are correct and we shouldn’t pretend otherwise.

Teachers who are apprehensive. Being a teacher is a profession. The loss of jobs is inevitable. The inference that can be drawn from this is that teachers risk having their jobs eliminated.

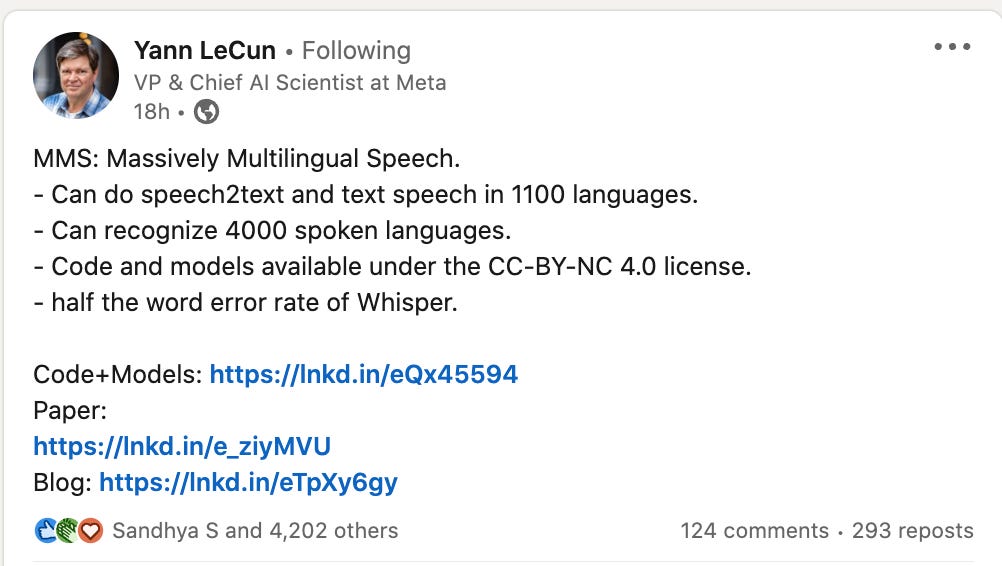

I think most teachers are safe, since teachers fulfill many roles and are essential to human development, but all courses are not immune. Once technology enables voice-to-voice translation and then improves, it is unclear what the value of learning a language will be.

We already have voice to text and text to voice through every day apps that are now installed on people’s phones.

Revenue. In an era of job loss, how will tuition-driven schools (both private K–12 and universities) survive in this world? Many of these schools depend on tuition support from middle-income families. The most expensive private K–12 schools that serve the most well-off will probably be fine, but those that serve middle-income families may be in a lot of trouble. Those that serve the less well-off and the middle class will struggle, especially since many are already struggling. That’s most schools. (And they’ll struggle even more if they fail to teach students who to thrive in an AI world; who is going to pay for their child to learn skills needed in a previous era)?

What this Means for Schools

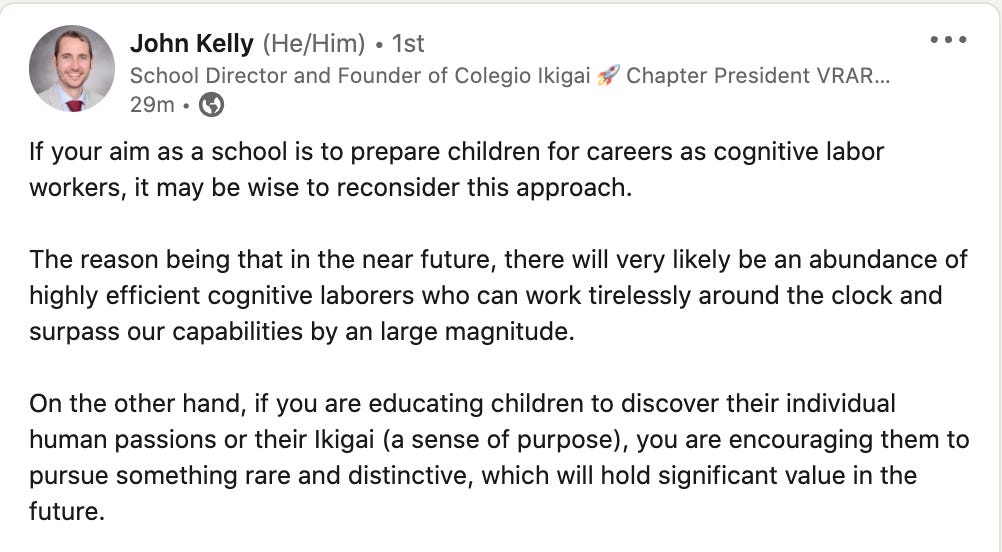

Training for the unknown. Schools have to start training students for the unknown, including helping them develop basic mechanisms to cope with anxiety and change, to reinvent themselves, and to develop soft skills (which will be explored more in a future essay).

“Nobody knows how the world will look in 2050 except that it will be very different from today. So the most important things to emphasize in education are things like intelligence, emotional intelligence, and mental stability. Because the one thing that they will need for sure is the ability to reinvent themselves repeatedly throughout their lives for the first time in history. We don't fully know what particular skills to teach young people because we just don't know in what kind of world they will be living. We do know they will have to reinvent themselves, especially if you think about something like the job market. Maybe the greatest problem they will face will be psychological. Because at least beyond a certain age, it's very, very difficult for people to reinvent themselves.” (Yuval Noah Harari).

A new essay will be written that goes into greater depth on the topic of soft skills. For now, I’ll share this thought about the potential irrelevance of focusing on cognitive skills:

The education system ought to get ready to repurpose and retrain its teachers. There is a possibility that learning a language will become significantly less valuable in the future. The same is true for the coding process. But even if there is no longer a demand for people with these skills, students will still require teachers, and teachers can instruct students in more than one subject. And their ability to instruct outside their current subject area will be made easier because AIs will be very good with the content; what will really be needed is teachers with really great “human skills” who can help students learn content as they interface with technology.

Knowledge of AI. It is important for educational institutions to get ready to have meaningful conversations with students about the new world of AI. These conversations need to be open and forthright while simultaneously providing comfort.

Want to Learn More?

Check out the book I edited: Chat(GPT): Navigating the Impact of Generative AI Technologies on Educational Theory and Practice.

Register for my Intro course with Sabba Quidwai.