Bauschard’s Initial Guide to Classroom Debate: Implementation and Assessment

Every person will spend far more time speaking, presenting, and verbally defending ideas than they will writing formal essays. Job interviews are spoken. Team meetings are spoken. Parent-teacher...

Why I Wrote This

I’ve seen a number of friends I’ve made on LinkedIn as part of the discussion related to AI and education take me up on my suggestion to try debating in the classroom. Some have asked me how I’d do it. To support those efforts, I’ve sketched out how I’d go about it, using a sample lesson on industrialization. Educators should adjust the lesson content as appropriate for the grade and objectives, just as expectations for writing a paper would change based on students age/experience and the learning objectives..

This is part of a larger project I’m working on, and I would greatly appreciate any feedback. My Subscribers can access this through a Google doc they can download.

What You Need to Know Before You Start

Here’s what I tell every teacher trying debate for the first time: you’re about to witness one of the most powerful learning trajectories you’ll see in your classroom. Most students don’t have significant experience debating, which means you get to watch them develop a completely new skill set from the ground up—imagine the satisfaction of teaching someone to write their very first essay and seeing them progress from there. That’s the opportunity you have. You just need to adjust your own expectations accordingly.

And here’s what makes this exciting: students improve at debating remarkably quickly. The more they do it, the better they get, and you’ll see an improvement trajectory just like you do with writing—except often faster because they get immediate feedback from their peers and can apply new strategies in the very next round. Debate involves using evidence and facts, so while they’re developing these argumentation skills, they’re simultaneously mastering content in a way that sticks because they’ve had to actively use it, defend it, and see it challenged.

One crucial piece of advice: integrating debate into the classroom shouldn’t be one teacher’s responsibility. If each class in a grade level had at least one debate by the end of October, the debates students have in each class by the end of December would be dramatically better. This distributed approach creates multiple practice opportunities while spreading the work across your faculty.

Also, all students don’t have to debate the same topic. For example, if you’re teaching the Industrial Revolution, you could give “The Industrial Revolution improved the lives of ordinary people in American cities” as a general framing, but then break it into multiple specific resolutions:

1. Resolved: The environmental costs of industrialization were justified by the economic development it enabled. This examines pollution, resource depletion, and ecological damage against material prosperity—forces long-term vs. short-term thinking.

2. Resolved: Government regulation of business during the Gilded Age did more harm than good. Explores laissez-faire capitalism vs. intervention, trust-busting, railroad regulation, and whether free markets or government oversight better served development.

3. Resolved: The rise of corporate monopolies was an inevitable and necessary stage of industrial development. Questions whether concentration of economic power (Standard Oil, Carnegie Steel) was economically efficient or socially destructive.

4. Resolved: Mechanization displaced more jobs than it created during the Industrial Revolution. Tackles technological unemployment, skill obsolescence, and whether innovation creates net employment gains or losses.

5. Resolved: The Industrial Revolution widened economic inequality more than it expanded overall prosperity. Requires weighing absolute gains in living standards against relative disparities between robber barons and workers.

6. Resolved: American industrialization depended primarily on exploiting immigrant labor rather than technological innovation. Examines whether cheap, exploitable workforce or technological advancement was the critical driver—and the moral implications of each.

These resolutions push students beyond simple “good or bad” judgments to analyze tradeoffs, causation, and competing values across economic, political, environmental, and social dimensions.

Make Observation Time Learning Time:the time students spend listening to other students’ debates should be learning time, not downtime.

When students observe their peers debating the Industrial Revolution resolution, they should be actively learning substantive historical content, not passively waiting for their turn—and this learning should be formalized through flowing (structured note-taking) and assessment. As one student argues that real wages increased 50-60% while another counters with data on 35,000 annual workplace deaths, observers should be recording both claims, the evidence citations (Bureau of Labor Statistics reports vs. factory investigation testimony), and how debaters weigh these competing facts, building a comprehensive understanding of the period’s economic and human costs.

When a debater distinguishes between Irish textile workers and African American steel workers to show how industrialization affected different groups unequally, observers learn crucial content about immigration patterns, occupational segregation, and the limitations of aggregate statistics—knowledge they must capture in their flows to later recall and apply. Students should note specific examples like the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, Jacob Riis’s photographic evidence, Hull House’s social services, or the Panic of 1893’s impact on unemployment, creating a detailed content map across multiple rounds that far exceeds what any single textbook chapter provides.

Then—and this is essential—teachers should test students on this content. Ask them to explain the difference between real and nominal wages, analyze why return migration rates suggest limits to “improvement,” or construct their own argument about whether technological unemployment was temporary or permanent. This ensures that observation time translates into accountable learning. This approach transforms debate rounds from entertainment into rigorous content instruction where students encounter the same material from multiple analytical angles, hear it defended with evidence, see it challenged and refined, and ultimately master both the historical facts and the frameworks for interpreting them.

Through debating this resolution, students learn to navigate conflicting historical evidence and make reasoned judgments about complex tradeoffs. For example, they might discover that while real wages increased by 50-60% during this period, workers simultaneously faced 12-16 hour workdays and suffered 35,000 workplace deaths annually by 1900, forcing them to grapple with whether material gains justify human suffering Students learn to question whose experience counts when we make historical generalizations—recognizing that Irish immigrants in textile mills faced different conditions than African Americans in steel foundries, or that second-generation children who accessed public education had vastly different opportunities than their parents who worked in factories.

They develop skills in weighing incommensurable values: is access to affordable consumer goods more important than childhood education, or the ability to escape rural poverty more significant than urban overcrowding that killed thousands in disease outbreaks? Students also learn to interrogate their sources critically, understanding that Jacob Riis’s photographs reveal suffering that wage statistics obscure, while labor bureau reports provide quantitative data that personal narratives cannot.

Ultimately, they discover that “improvement” itself is a contested concept requiring them to articulate clear frameworks for judgment rather than simply marshaling facts—a skill that transfers far beyond history class into any domain requiring ethical reasoning about progress, development, and human welfare.

Why This Matters Even More in the AI Era

These judgment skills become essential in an AI-dominated world because machines excel at processing information but cannot determine what matters or why. While AI can instantly compile every statistic about Industrial Revolution wages, workplace deaths, and consumption patterns, it cannot decide whether a 50% wage increase justifies 35,000 annual deaths, or whether we should prioritize material prosperity over human dignity—these require human frameworks of value that must be explicitly articulated and defended.

As AI systems make increasingly consequential decisions in healthcare, criminal justice, education, and economic policy, humans must be able to interrogate the values embedded in algorithmic recommendations, question whose experiences are centered or marginalized in training data, and recognize when quantifiable metrics obscure moral dimensions that resist measurement.

Students who learn to weigh incommensurable goods, identify whose perspective defines “improvement,” and construct explicit frameworks for judgment develop exactly the capacities needed to govern AI systems rather than be governed by them. In a world where AI can generate persuasive arguments for any position, the ability to critically evaluate competing claims, recognize that “progress” is contestable, and make reasoned choices among tragic tradeoffs becomes the distinctly human contribution to human-AI collaboration.

These aren’t supplementary “critical thinking” skills—they are the core competencies that determine whether humans retain meaningful agency in setting societal priorities, or whether we abdicate those decisions to systems optimized for goals we never consciously chose.

The Bigger Question: Why Not Make Debate Required?

Adding a debate class would help a lot. Before we get to more practical details, let’s address the bigger question: Why should debate be a required course for all students in early middle school (grades 6-8) or freshman year of college, not just an elective for the motivated few?

The answer is simple: We already require composition courses because writing matters. Debate should be required too, because speaking and argumentation matter just as much—arguably more.

Consider the asymmetry in our current educational priorities. Every middle school student takes multiple years of English composition. Every college has freshman writing seminars or composition requirements. We’ve collectively decided that the ability to construct written arguments, cite sources, and organize ideas on paper is fundamental to educated citizenship. And we’re right—it is fundamental.

But here’s what we’ve missed: Every person will spend far more time speaking, presenting, and verbally defending ideas than they will writing formal essays. Job interviews are spoken. Team meetings are spoken. Parent-teacher conferences are spoken. City council public comments are spoken. Negotiations with bosses, landlords, and service providers are spoken. Democratic deliberation happens through spoken discourse, not through everyone submitting carefully-edited position papers.

Yet we spend years teaching students to write persuasively and almost no time teaching them to speak persuasively. We teach thesis statements and topic sentences but not how to construct an oral argument under time pressure. We teach MLA citation format but not how to defend your sources when someone challenges them in real time. We teach students to revise their writing but not how to adjust their argument when an opponent exposes a weakness.

This is pedagogical malpractice. If we believe argumentation skills are essential—and clearly we do, given the time we invest in teaching written argumentation—then we must teach oral argumentation with equal seriousness.

Building a Foundation That Every Class Reinforces

Teaching debate early in a student’s academic career creates a foundation that every subsequent course reinforces. Imagine a seventh-grader who takes a semester-long debate course using the framework in this guide. They learn to construct claim-evidence-warrant arguments. They learn to evaluate source credibility. They learn to anticipate counterarguments. They learn to think strategically under pressure.

Now that student enters eighth-grade history. When the teacher assigns an essay about the causes of World War I, the student doesn’t just list facts—they automatically structure arguments: “The primary cause was X because [evidence], which proves Y because [warrant], and while some historians argue Z, that interpretation fails to account for [counterargument].” The teacher doesn’t have to teach argumentation from scratch; they’re reinforcing skills the student already has.

The same thing happens in ninth-grade biology when the student has to present research findings, in tenth-grade civics when analyzing policy proposals, in eleventh-grade literature when defending interpretations. Every year, every teacher builds on the foundation that debate established. By the time the student reaches college, argumentation isn’t something they’re learning—it’s something they’re refining.

Compare this to our current approach, where we teach argumentation implicitly and inconsistently across the curriculum. One teacher values evidence, another values creativity, a third values personal reflection. Students never develop coherent standards for what makes a strong argument because the standards keep shifting. By requiring debate early, we establish consistent standards that the entire faculty can reference: “Remember from your debate class how you constructed claim-evidence-warrant arguments? Use that structure here.”

The AI Revolution Makes This Urgent

And finally, the AI revolution makes these skills exponentially more important, not less. AI can now generate competent written text. ChatGPT can write your essay. Claude can draft your research paper. Within a few years, AI will produce first drafts that are grammatically correct, properly cited, and structurally sound for virtually any written assignment.

What AI cannot do—what will remain distinctly human—is defend those ideas when challenged, adjust arguments in response to opposition, evaluate competing claims in real time, and persuade other humans through dynamic interaction. These are debate skills. In an AI-saturated world, the ability to think on your feet, respond to unexpected questions, and engage in genuine intellectual discourse becomes the scarce, valuable competency.

If we continue to spend years teaching students skills that AI can replicate (writing standard five-paragraph essays) while neglecting skills that AI cannot replicate (defending ideas under cross-examination), we’re preparing students for a past that no longer exists.

The students entering middle school today will graduate college in 2035. By then, AI will be ubiquitous in ways we can barely imagine. The question every employer, every graduate program, every civic institution will ask is: “Can you do what AI cannot?” Students who have spent years practicing debate will answer yes. Students who spent those years perfecting the format of their bibliography will not.

The Bottom Line

We require composition because we believe written argumentation is fundamental. We should require debate because spoken argumentation is equally fundamental—and in the AI era, it may be the skill that matters most. The schools that recognize this early and build debate into their core curriculum aren’t experimenting with an interesting elective. They’re giving their students the literacy that will define success in the 21st century.

Part 1: Introducing Students to the Process

Day 0: What Is Classroom Debate? (30-45 minutes)

Teacher Script:

“For the next several months, we’re going to learn history differently. Instead of me telling you what to think about historical events, you’re going to argue with each other about what they mean.

This might feel uncomfortable at first. You’re used to trying to figure out what the teacher wants to hear. In debate, there’s no single ‘right answer’ I’m looking for. There are better and worse arguments, and you’ll learn to tell the difference.

Here’s what debate is NOT:

It’s not fighting or being mean to each other

It’s not about who talks louder or longer

It’s not about winning by any means necessary

It’s not about your personal opinion mattering more than evidence

Here’s what debate IS:

It’s structured disagreement with rules and time limits

It’s defending a position with historical evidence

It’s listening carefully to find weaknesses in opposing arguments

It’s accepting that you might have to argue for a position you personally disagree with

Why are we doing this? Because this is how you learn to think. Not what to think—how to think. How to build an argument. How to test evidence. How to change your mind when someone presents better proof. How to hold two competing ideas in your head and figure out which one fits the facts better.

Also, this is how the world actually works. Scientists debate. Lawyers debate. Congress debates. Citizens debate policy. Scholars debate history. If you can’t argue effectively—if you can’t defend your ideas and challenge others’ ideas—you can’t fully participate in democracy.”

Here’s what a typical debate cycle looks like:

You’ll get a debatable question about something we’re studying. You’ll be randomly assigned a side—sometimes you’ll agree with it, sometimes you won’t. You’ll research using real sources: primary documents, textbooks, scholarly articles. You’ll work in teams, with different jobs—some of you will be speakers, some will be researchers, some will be judges. Then we’ll have the debate. Judges will decide which side argued better. Then we’ll reflect on what we learned.

And here’s the key: Everyone rotates through every role. If you’re terrified of public speaking, you won’t start as a speaker. You’ll start as a researcher or a judge. You’ll build up to it. By the end of the semester, you’ll have done every role, developed every skill.

One more important thing: You will struggle, and that’s the point.

In your first debate, you’ll forget arguments. You’ll freeze when someone asks you a question. You’ll wish you’d prepared better. Good. That’s learning. I’m not expecting perfection—I’m expecting effort and growth.

I’m not grading you on whether your team wins. I’m grading you on whether you constructed a solid argument, whether you used credible evidence, whether you listened to the other side, whether you improved from last time.

Some of you will lose debates and still earn A’s because you performed excellently. Some of you will win debates and earn B’s because you didn’t improve. The debate outcome and your grade are separate things.

Why This Introduction Matters

You’re doing several crucial things in this speech:

Addressing the content concern immediately. Parents and students worry debate means “no real learning.” You’re showing them that debate requires more content knowledge, not less, because you have to use facts strategically.

Managing anxiety about performance. By explaining role rotation and separating grades from winning, you’re telling students “You won’t be thrown into the deep end. We’ll build up to it.”

Explaining the ‘why’ before the ‘what’. Students work harder when they understand the purpose. You’re connecting debate to democracy, college, careers—things they care about.

Normalizing struggle. Saying “You will freeze and that’s okay” gives permission to be imperfect. This reduces performance anxiety.

Being honest about discomfort. You’re not pretending this will be easy. You’re saying it will be hard and worth it.

What students hear:

“I’ll still learn the history I need to know”

“I won’t have to speak first if I’m scared”

“My grade isn’t based on winning”

“The teacher expects me to struggle at first”

“This connects to my future”

What parents hear (when students relay this):

“My kid is learning critical thinking”

“There’s a clear pedagogical reason for this”

“The teacher has thought about shy kids”

“Grading is fair and separated from competition”

This introduction does the heavy lifting of selling students on debate before they experience it. By the time you get to Goldilocks, they understand the framework and are ready to try.

The “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” Mini-Debate

Purpose: Give students a low-stakes practice debate on a topic they already know before tackling historical content.

Why Goldilocks? Everyone knows the story, it has clear debate-worthy issues (trespassing, property damage, intent), and it’s non-threatening. Students can focus on learning debate structure without worrying about content knowledge.

The Story (As Told to Students)

Teacher Script:

“Before we debate historical topics, we’re going to practice with a story you all know: Goldilocks and the Three Bears. But this time, we’re going to treat it like a legal case.

Here’s what happened:

The Three Bears—Papa Bear, Mama Bear, and Baby Bear—lived in a house in the woods. One morning, they made porridge for breakfast, but it was too hot to eat. While they waited for it to cool, they went for a walk.

While the bears were gone, a girl named Goldilocks was walking through the woods. She came upon the bears’ house. The door was unlocked. Goldilocks opened the door and walked inside without permission. No one was home. The bears had not invited her.

Once inside, Goldilocks saw three bowls of porridge on the table. She was hungry. She tasted Papa Bear’s porridge—it was too hot. She tasted Mama Bear’s porridge—it was too cold. She tasted Baby Bear’s porridge—it was just right, and she ate the entire bowl.

Then Goldilocks saw three chairs in the living room. She was tired. She sat in Papa Bear’s chair—it was too hard. She sat in Mama Bear’s chair—it was too soft. She sat in Baby Bear’s chair—it was just right, but when she leaned back, the chair broke into pieces.

Then Goldilocks went upstairs where she found three beds. She was very tired. She lay on Papa Bear’s bed—it was too hard. She lay on Mama Bear’s bed—it was too soft. She lay on Baby Bear’s bed—it was just right, and she fell asleep.

Soon the Three Bears came home. They discovered someone had been eating their porridge. They found Baby Bear’s bowl was empty. They saw someone had been sitting in their chairs. They found Baby Bear’s chair was broken. They went upstairs and found Goldilocks asleep in Baby Bear’s bed.

Goldilocks woke up, saw the three bears, screamed, jumped out of bed, ran down the stairs, and ran away into the woods. She never came back.

The bears called the police. They want Goldilocks arrested and punished.

The question we’re debating: Did Goldilocks commit a crime and should she be punished?

Key Facts for Debate Preparation

Distribute this handout to students:

FACTS OF THE CASE:

The bears’ door was unlocked but closed

Goldilocks opened the door and entered without permission

No one was home; the bears had not invited her

Goldilocks ate an entire bowl of porridge that didn’t belong to her

Goldilocks broke a chair (Baby Bear’s chair)

Goldilocks was found asleep in Baby Bear’s bed

When discovered, Goldilocks fled immediately

The story doesn’t tell us Goldilocks’s age, but she’s often depicted as a young child (maybe 7-9 years old)

The story doesn’t say whether Goldilocks was lost, hungry, or in danger

There’s no evidence Goldilocks intended to damage the chair—it broke when she sat in it

POSSIBLE LEGAL ISSUES:

Trespassing: Entering someone’s property without permission

Breaking and Entering: Entering someone’s home unlawfully (though the door was unlocked)

Theft: Taking and consuming property that doesn’t belong to you (the porridge)

Vandalism/Property Damage: Breaking the chair

Intent: Did Goldilocks mean to commit crimes, or was it an accident?

Age/Capacity: If she’s a child, should she be held responsible like an adult?

Setting Up the Debate

Resolution: “Goldilocks committed a crime and should be punished.”

10-Minute Team Preparation:

“I’m going to divide you randomly into three groups:

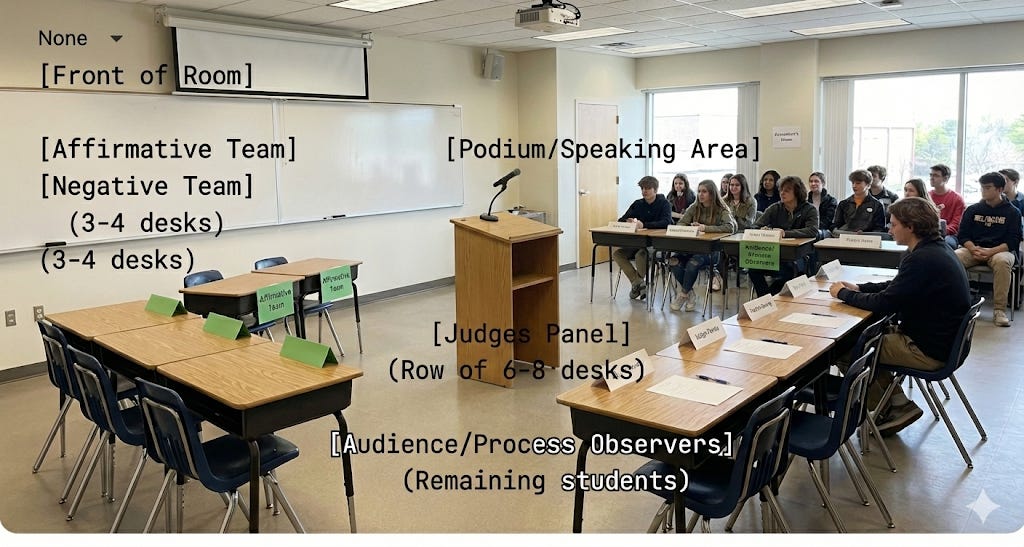

Affirmative Team (Prosecution): Your job is to argue that YES, Goldilocks committed crimes and should be punished. Think like a prosecutor. What laws did she break? What evidence proves it?

Negative Team (Defense): Your job is to argue that NO, Goldilocks should not be punished. Think like a defense attorney. Was it really a crime? Are there excuses or explanations? Should a child be punished?

Judges: Your job is to listen to both sides and decide which team makes better arguments. You’ll need to take notes.

You have 5 minutes to brainstorm with your team. Come up with at least three arguments for your side.”

Sample Arguments (To Share After the Debate)

AFFIRMATIVE (Prosecution) Arguments:

Argument 1: Goldilocks committed trespassing and breaking and entering.

Evidence: She entered a home that wasn’t hers without permission

The door being unlocked doesn’t make it legal—you can’t just walk into someone’s house

She knew she didn’t live there; she saw three bowls, three chairs, three beds

Argument 2: Goldilocks committed theft.

Evidence: She ate an entire bowl of porridge that belonged to Baby Bear

She took property that wasn’t hers without paying or asking permission

This deprived Baby Bear of his breakfast

Argument 3: Goldilocks committed vandalism/property damage.

Evidence: She broke Baby Bear’s chair

Even if she didn’t mean to break it, she used someone else’s property without permission and damaged it

The bears now have to replace the chair at their expense

NEGATIVE (Defense) Arguments:

Argument 1: There was no criminal intent.

Goldilocks didn’t break into the house—the door was unlocked and open

She may have thought no one lived there, or that it was abandoned

She didn’t plan to steal or damage anything; she was lost and hungry

Argument 2: She’s a child and shouldn’t be held to adult standards.

Young children (age 7-9) don’t have full understanding of property laws

The legal system recognizes that children lack the mental capacity for criminal responsibility

Her running away shows she knew she made a mistake—that’s a child’s fear response

Argument 3: The punishment should fit the circumstances.

No one was hurt; this was property damage only

Goldilocks already fled in terror, which is a consequence

The bears could be compensated without criminal punishment (civil remedy, not criminal)

She was a hungry, possibly lost child—she needs help, not jail

The Debate Format (Simplified)

Total time: 15-20 minutes

Affirmative Opening (2 min): Present your case for why Goldilocks should be punished

Negative Opening (2 min): Present your case for why she shouldn’t

Cross-Examination (3 min): Each side gets to ask the other side 2-3 questions

Affirmative Response (1 min): Answer the negative’s main arguments

Negative Response (1 min): Answer the affirmative’s main arguments

Judges Deliberate (3 min): Judges discuss quietly and take notes

Judge Decision (2 min): One judge announces decision with one reason

Class Discussion (5 min): What did we learn about debate?

Critical Debrief Questions

After the Goldilocks debate, ask:

“How many of you personally agreed with the position you argued?”

Point: You can argue effectively for positions you don’t personally hold

This is a crucial democratic skill

“What made the stronger arguments stronger?”

Students will say: “They used specific evidence,” “They answered the other side,” “They made sense”

Point: Good arguments need evidence + reasoning, not just opinions

“Judges: Did you vote based on who you agreed with, or based on who argued better?”

Ideally, judges explain they evaluated arguments even if they personally disagreed

If they voted on personal opinion, this shows why we need judging criteria

“What was harder than you expected? What was easier?”

Normalizes that debate has a learning curve

Identifies specific skills to work on (speaking clearly, answering questions, etc.)

“Did anyone change their mind during the debate?”

If yes: This is intellectual honesty—changing your mind when you hear better evidence

If no: That’s okay, but did you understand the other side’s arguments better?

“What would make your arguments stronger next time?”

Students will say: “More examples,” “Better answers to their questions,” “Being more organized”

Write these down—they become the criteria for your rubrics

Why This Works

Goldilocks gives students everything they need to practice debate structure:

✓ Clear positions: Guilty vs. Not Guilty

✓ Evidence everyone knows: The story facts

✓ Multiple valid arguments on both sides: No obvious “right” answer

✓ Low emotional stakes: It’s a fairy tale, not their identity

✓ Requires reasoning: They have to explain why facts matter

✓ Anticipates opposition: Both sides have to deal with counterarguments

And it teaches the key insight: Even a simple children’s story can be debated intelligently when you focus on evidence and reasoning rather than just opinions.

After Goldilocks, students understand: “Oh, this is what debate is. We look at the same facts and argue about what they mean. And judges decide based on whose reasoning is stronger.”

That understanding prepares them for debating complex historical questions where the facts are contested and the interpretations are even more challenging.

Teacher Tip: Save the “Sample Arguments” handout for after the debate. Don’t give it to students beforehand—let them figure out arguments themselves. Then after the debate, share the handout and ask: “Which of these arguments did you think of? Which ones surprised you? Which side’s arguments are stronger?”

This teaches them that there are usually more arguments available than they initially thought, and that preparation and research help you find them.

Introducing the Role System

Teacher Script:

“In our debates, not everyone has the same job. Just like in sports where you have different positions, debate has different roles. Over the semester, you’ll rotate through all of them.

Speakers: You make the arguments in front of the class. You have to know the evidence, organize it into a persuasive case, and deliver it under time pressure.

Evidence Researchers: You’re the team’s intelligence unit. You find sources, evaluate their credibility, create evidence cards, and brief the speakers on what you found.

Cross-Examiners: You ask questions to expose weaknesses in the other side’s arguments. You’re testing their evidence and setting up your own team’s arguments.

Judges: You take notes on everything, evaluate which arguments are stronger, and make a decision with reasoning. You have to be fair even if you personally disagree with who wins.

Process Observers: You’re the referees. You track time, verify evidence citations, and keep the debate running smoothly.

Why rotate? Because each role teaches you different skills. Speakers learn public speaking and argument construction. Researchers learn source evaluation and evidence synthesis. Cross-examiners learn strategic questioning. Judges learn critical analysis and fair evaluation. Observers learn meta-cognition—seeing the debate from above.

By the end of the semester, you’ll have done all of these roles. That means you’ll develop all of these skills.”

Setting Classroom Norms

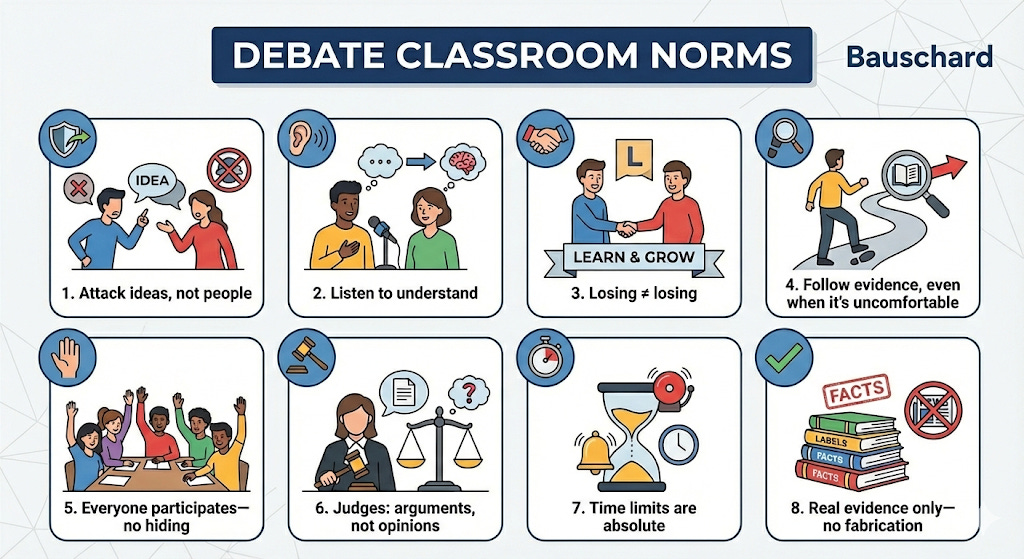

1. Disagree with ideas, not people.

The Principle: Attack arguments, not the person making them. Focus on what was said, not who said it.

What this looks like in practice:

✓ GOOD:

“Your evidence is weak because it doesn’t cite a source.”

“That argument has a logical flaw—you’re assuming X, but you haven’t proven X.”

“I disagree with your interpretation of that data.”

“Your evidence contradicts itself. You said wages went up, but then you said people were poorer.”

✗ NOT OKAY:

“You’re stupid.”

“That’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard.”

“You obviously didn’t understand the reading.”

“Only an idiot would think that.”

Eye-rolling, sighing, or making faces while someone speaks

Why this matters: When you attack the person, they stop listening and get defensive. When you attack the argument, you can actually change minds. Plus, you have to argue with these people again next week in a different debate—don’t make enemies.

Teacher enforcement:

First offense: Stop debate, correct language, model proper phrasing, continue

Second offense: Deduct points on “Professional Demeanor” rubric criterion

Third offense: Remove from speaking role, become observer for this debate

Example intervention: “Stop. Marcus, what you just said crossed the line. You can say ‘Your evidence doesn’t support your claim.’ You cannot say ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about.’ Rephrase your criticism to focus on the argument, not on Sarah. Let’s continue.”

2. Listen to understand, not just to respond.

The Principle: You can’t refute an argument you didn’t actually hear. Listen actively to understand what the other side is really saying before you respond.

What this looks like in practice:

✓ GOOD:

Taking notes while opponent speaks

Asking clarifying questions in cross-examination: “When you said ‘economic improvement,’ did you mean wages or standard of living?”

Responding to what they actually argued, not what you expected them to argue

Paraphrasing their position before refuting it: “You claim that reforms happened quickly. But your own evidence shows 25 years passed...”

✗ NOT OKAY:

Preparing your response while opponent is still talking

Interrupting mid-speech

Responding to a strawman: “My opponent thinks everything was perfect!” (when they never said that)

Saying “I wasn’t really listening, but...”

Looking at your notes instead of at the speaker

Why this matters: If you respond to arguments they didn’t make, judges notice. You lose credibility. Also, sometimes opponents make arguments you hadn’t thought of—you learn by listening.

Example of good listening: Opponent: “Cities offered economic opportunity.” You (in rebuttal): “My opponent claimed cities offered economic opportunity. But opportunity for whom? Their own evidence shows women earned half what men earned, and children worked 12-hour days. That’s not opportunity—that’s exploitation.” [You heard them, acknowledged their point, then refuted it with evidence.]

Example of bad listening: Opponent: “Cities offered economic opportunity.” You (in rebuttal): “Cities were terrible! People lived in slums!” [You didn’t engage what they said. You just stated your position. Judges won’t give you credit for this.]

Teacher prompt during prep: “Before you write your response speech, tell me the three strongest arguments the other side made. Not the ones you wanted them to make—the ones they actually made.”

3. Losing a debate doesn’t make you a loser.

The Principle: Sometimes the other side has better evidence or makes better arguments. That’s how you learn. Debate outcome ≠ personal worth.

What this looks like in practice:

✓ GOOD RESPONSES TO LOSING:

“We lost because they had that Census data and we didn’t. Next time I need to research statistics, not just general sources.”

“Their cross-examination exposed the gap in our argument. We should have anticipated that question.”

“Judges voted for them because their reform argument was stronger. That makes sense—I’d probably have voted the same way.”

Congratulating the winning team

✗ NOT OKAY RESPONSES TO LOSING:

“The judges were biased!”

“This is unfair!”

Refusing to participate in debrief

Blaming teammates

Sulking or storming out

Claiming “We actually won but the judges are wrong”

Why this matters: You’ll debate 6-8 times this semester. Statistically, you’ll lose some. If losing destroys you, you can’t learn. The best debaters lose all the time—and they learn from every loss.

Teacher response to healthy disappointment: “I can see you’re disappointed. That shows you cared and worked hard. Now let’s figure out what you learned. Pull out your rubric—where did you score well? Where do you need to improve? Those answers are your roadmap for next debate.”

Teacher response to unhealthy upset: “I understand you’re frustrated. But let me ask you something: can you point to specific places in the judge decisions where they were unfair? [Student usually can’t.] What I see is that judges explained their reasoning. You can disagree with their reasoning, but that’s debate. Sometimes your arguments don’t win. That doesn’t mean the process was rigged.”

Class discussion after first debate: “Raise your hand if your team won. Okay. Now keep your hand up if you think you performed perfectly with no room for improvement. [Hands go down.] Exactly. Winning doesn’t mean you were perfect. Now raise your hand if your team lost. Keep your hand up if you learned something valuable about how to argue better next time. [Hands stay up.] That’s the point. We’re all learning, whether we win or lose.”

4. Change your mind when evidence warrants it.

The Principle: Intellectual honesty matters more than being “right.” If someone presents better evidence or reasoning, it’s a strength to acknowledge that, not a weakness.

What this looks like in practice:

✓ GOOD:

“I came into this debate thinking the Industrial Revolution was entirely negative, but the wage data the Affirmative presented is actually pretty convincing. I need to revise my understanding.”

As a judge: Voting for the side you personally disagree with because their arguments were stronger

Telling your teammates: “You know, they have a point about the reforms. We should adjust our strategy.”

Writing in reflection: “I changed my mind about this historical question because of the evidence presented.”

✗ NOT OKAY:

Ignoring evidence because it contradicts what you want to believe

Refusing to acknowledge strong opposing arguments

As a judge: Voting for your personal opinion instead of evaluating arguments

Saying: “I don’t care what the evidence says, I’m sticking with my position”

Why this matters: This is what scientists, historians, and citizens in a democracy must do—follow evidence even when it’s uncomfortable. If you can’t change your mind in a classroom debate, you won’t be able to do it when it matters in real life.

Real example to share with students:

“I once judged a debate where a student was assigned to argue that a particular policy was effective. She researched it expecting to find evidence supporting that position. Instead, she found overwhelming evidence the policy had failed. In the debate, she presented the strongest case she could with the evidence she could find, but after the debate she said, ‘I went into this thinking one thing, and the research completely changed my mind.’ That’s intellectual integrity. That’s what we’re developing here.”

Teacher modeling: During debrief, occasionally say: “You know, I came into this debate thinking the Negative had the easier case to make, but the Affirmative’s argument about [X] was really compelling. I need to reconsider my assumptions about this topic.”

[Students see that even the teacher is willing to say “I learned something / I changed my mind.”]

5. Everyone participates. Hiding is not an option.

The Principle: Growth happens outside comfort zones. You will have a role in every debate. You will participate.

What this looks like in practice:

✓ PARTICIPATION THAT COUNTS:

Taking on assigned role even if it’s uncomfortable

Speaking up during team preparation

Asking questions when you don’t understand

Doing your research thoroughly

Providing constructive feedback to teammates

Accepting feedback from others

✗ HIDING BEHAVIORS:

“I’ll just observe this debate”

Letting teammates do all the work during prep time

Volunteering only for low-visibility roles repeatedly

Skipping research days

Not speaking during team meetings

Asking to “just help in the background”

Why this matters: The role rotation system means you’ll do easier roles before harder ones. But you have to actually do them. Students who hide in Debate 1 are still hiding in Debate 6. Students who push through discomfort in Debate 1 are confident by Debate 6.

For anxious students, the teacher says:

“I know speaking terrifies you. I’m not throwing you in as a speaker in Debate 1. You’re starting as an evidence researcher. Your job is to find sources and create evidence cards. That’s private work, not performance. In Debate 2, you might be a judge—still no speaking to the class. By Debate 3 or 4, you’ll try cross-examination, where you ask questions with a partner’s support. By Debate 5, you’ll be ready for a speech, and you’ll have watched other students model it 8-10 times. This is gradual, but you will do every role eventually.”

For students who want to coast:

“You don’t get to skip roles because they’re hard. The student who’s naturally good at public speaking doesn’t get to be a speaker every time—they need to learn research and judging too. The shy student doesn’t get to be a researcher every time—they need to learn speaking. Everyone does everything. That’s non-negotiable.”

Accountability structure:

Portfolio requires documentation of all roles

Missing a role = incomplete portfolio = grade penalty

BUT: Struggling in a role is fine. Avoiding a role is not.

6. Judges are neutral arbiters. Personal opinions stay out of decisions.

The Principle: When you’re a judge, you evaluate arguments based on evidence and reasoning presented in the debate, not based on what you personally believe about the topic.

What this looks like in practice:

✓ GOOD JUDGING:

“I personally think the Industrial Revolution was harmful, but the Affirmative team presented stronger evidence that wages increased. They won the economic argument, and the Negative didn’t adequately refute it. Vote: Affirmative.”

Taking detailed notes on both sides

Citing specific arguments in your decision

Explaining why one piece of evidence was more credible than another

Voting against your personal opinion because the arguments warranted it

✗ BAD JUDGING:

“I agree with the Negative’s position, so they win.”

“I didn’t like how the Affirmative speaker talked, so Negative wins.”

Making a decision without notes or explanation

“Both sides were good, so it’s a tie.” [Force yourself to decide!]

Letting your personal views about the topic determine the outcome

Why this matters: Judges learn the hardest skill of all—evaluating arguments fairly even when you disagree with the conclusion. This is what jurors must do. What editors must do. What voters should do.

Teacher coaching for judges:

Before first debate: “Your job is to forget what YOU think about the Industrial Revolution. Pretend you know nothing. Both teams will try to convince you. Whoever convinces you with evidence and reasoning presented in this debate wins. Not whoever you already agreed with.”

Example of good judge reasoning:

“I went into this debate believing that working conditions were the most important factor. However, the Affirmative presented three separate pieces of evidence showing that people voluntarily chose to move to cities and stay there, which suggests that even with bad conditions, they preferred city life to farm life. The Negative argued people were forced to move, but provided no evidence for this claim. Based on the arguments presented in THIS DEBATE, Affirmative wins, even though I personally still think working conditions matter more than wages.”

Example of bad judge reasoning:

“I think the Industrial Revolution was bad because my family came from a farm town and my grandparents have stories about how hard life was in cities. So Negative wins.”

[This judge didn’t evaluate the debate—they just stated their opinion.]

If a judge does this:

Teacher addresses whole class: “This decision didn’t explain which arguments won or lost in the debate. It explained what the judge personally believes. Let me show you the difference...”

[Then model what the decision should have looked like, using specific arguments from the debate.]

7. Time limits are absolute. The timer doesn’t care about your feelings.

The Principle: Speeches have time limits. Cross-examination has time limits. When time expires, you stop immediately. No exceptions.

What this looks like in practice:

✓ GOOD TIME MANAGEMENT:

Practicing speech beforehand to ensure it fits in time

Watching the timer during your speech

Wrapping up your final point when you see “30 seconds” warning

Stopping mid-sentence if necessary when time is called

Planning which arguments to prioritize if you’re running short on time

✗ NOT OKAY:

“Just let me finish this sentence!” [after time is called]

“I just need 30 more seconds!”

Talking faster and faster to cram everything in

Ignoring time warnings

Blaming the timer: “I would have won if I had more time”

Why this matters: Real debates have time limits. Job interviews have time limits. Presentations have time limits. Learning to organize your thoughts within a time constraint is a life skill.

How time enforcement works:

Process observer is the official timekeeper (this is their role, not the teacher’s)

Timer holds up signs: “2 MINUTES LEFT” then “30 SECONDS” then “TIME”

When “TIME” sign goes up, speaker must stop

If speaker continues beyond 5 seconds, judges are instructed: “Do not count any arguments made after time expired”

Rubric criterion “Time Management” directly penalizes going significantly over or under

Teacher explanation to students:

“In a real debate tournament, judges stop flowing (taking notes) the moment time expires. Anything you say after that doesn’t count. We’re doing the same thing here. If you go over time, judges won’t consider those arguments. You hurt your own case by not managing time well.”

Sympathetic but firm response when student goes over:

“I know you had more to say. That’s actually a good sign—it means you had strong arguments. But part of debate is fitting your best arguments into the time you have. Next time, prioritize your three strongest points instead of trying to make six points. Quality over quantity.”

Practice strategy:

During prep days, have teams practice speeches with timer. Teach them:

Write more than you’ll say, then cut to the best parts

Know which argument you’ll skip if you’re running short

Build in a 15-second buffer—aim to finish at 4:45 for a 5-minute speech

8. Evidence must be real and cited. Making up sources is academic dishonesty.

The Principle: Every factual claim must come from a real, citable source. Fabricating evidence or sources is cheating and will be treated as such.

What this looks like in practice:

✓ PROPER EVIDENCE USE:

“According to Robert Whaples in his 2005 EH.Net Encyclopedia article, real wages increased 60% between 1860 and 1890.”

Evidence cards include: Author, Title, Publication, Date, Page number (if applicable), URL (if applicable)

Saying “I don’t have a source for that, so I can’t make that claim” during prep

If asked in cross-ex “What’s your source?” being able to provide it immediately

✗ ACADEMIC DISHONESTY:

“Studies show...” [no specific study named]

“Experts agree...” [no specific experts named]

“I read somewhere...” [no source]

Making up statistics: “75% of workers died in factories” [no source]

Citing a source that doesn’t exist: “According to Johnson’s 1890 study...” [there is no Johnson study]

Copying a speech from the internet and presenting it as your own

Using a quote from a source but changing the words to say something the source didn’t say

Why this matters:

Academic integrity: In college, this gets you expelled. In professional life, it destroys your credibility.

Debate fairness: If you can make up evidence, debate becomes “who lies best” instead of “who argues best.”

Real-world consequences: Journalists who fabricate sources lose their jobs. Scientists who fake data lose their careers.

How we verify evidence:

Evidence researchers must submit evidence cards with full citations

Process observer may challenge evidence during debate: “I need to see the source for that statistic”

Teacher does spot-checks: randomly selects 2-3 pieces of evidence per debate and verifies sources exist

If evidence is questionable, burden is on the team to produce the actual source

If fabrication is discovered:

During debate: “Stop. That evidence has been challenged. [Student name], can you produce the source right now?”

If yes: Continue

If no: “That evidence is struck from the record. Judges will disregard it. We’ll discuss consequences after the debate.”

After debate:

Zero on that role rubric (automatic F for that debate)

Required to redo the debate in a different role with proper evidence

Academic dishonesty report per school policy

Parent contact

Serious conversation about integrity

Prevention is better than punishment:

Before first graded debate, full class workshop on citations:

What counts as a source (peer-reviewed articles, books, government data, credible news, primary documents)

What doesn’t count as a source (Wikipedia, random websites, “I heard,” “my cousin said”)

How to create a proper citation

How to create evidence cards

Practice: Give students a source, have them create a proper evidence card

Make it clear:

“If you’re not sure whether a source is credible or how to cite it, ask me during prep time. I will help you. What I won’t tolerate is making up sources or using sources you know are fake. That’s the one thing in this class that will earn you an automatic F.”

The Growth Mindset Framework

Before the first real debate, show students this:

“You will not be good at this immediately. That’s normal and expected. Here’s what growth looks like:

First debate: You’ll forget your arguments mid-speech. You’ll freeze during cross-examination. You’ll struggle to take notes as a judge. This is NORMAL.

Third debate: You’ll start to get comfortable with your role. Your speeches will be more organized. Your questions will be sharper. Your judge decisions will show clearer reasoning.

Sixth debate: You’ll see how different roles connect. Being a judge taught you what speakers need to do. Being a cross-examiner taught you how to anticipate questions as a speaker.

I’m not grading you on being perfect. I’m grading you on:

Meeting the specific criteria for your role (that’s the rubric)

Improving from one debate to the next (that’s your portfolio)

Taking intellectual risks even when it’s uncomfortable

The student who argues brilliantly for a position they don’t believe in? That’s the student who’s really learning.”

Part 2: Getting Started - Debate Zero

Why You Need a Practice Debate

Before you run your first graded debate, you need to demystify the process. Students are nervous about:

Speaking in front of the class

Not knowing what “good” debate looks like

Being judged by their peers

Failing at something they’ve never tried

Debate Zero solves this problem. It’s a low-stakes practice round where students learn the format, try different roles, and make mistakes without grade consequences.

You may wish to consider extra credit for this debate.

How Debate Zero Works

Timeline: One week before your first graded debate

Format: Simplified 30-minute debate

First Affirmative Speech (3 min)

Cross-Examination by Negative (2 min)

First Negative Speech (3 min)

Cross-Examination by Affirmative (2 min)

Affirmative Rebuttal (2 min)

Negative Rebuttal (2 min)

Affirmative Close (2 min)

Negative Close (2 min)

Judge Decision (5 min)

Whole Class Debrief (10 min)

The Resolution: Something students already know about

Don’t use historical content for Debate Zero. Use something students can argue about immediately without research:

Good Debate Zero Resolutions:

“The school day should start at 9:00 AM instead of 8:00 AM”

“Students should be allowed to use phones during lunch”

“Homework should be banned on weekends”

“The voting age should be lowered to 16”

“School uniforms should be required”

“Summer vacation should be shorter with more breaks during the year”

Why these work: Students have opinions, lived experience, and can generate arguments on the spot. They don’t need to research; they can focus on learning the debate process.

Debate Zero Structure

Day 1 (20 minutes): Introduction and Assignment

Explain the format (use the script from “Introducing Students to the Process”)

Present the resolution - have students vote on which topic they want from a list

Randomly assign roles:

Affirmative Team (3 students)

Negative Team (3 students)

Judges (remaining students)

Give homework: “Think of three arguments for your side. No formal research required—just brainstorm.”

Day 2 (50 minutes): Debate Zero + Debrief

0:00-0:10 - Teams huddle

Share brainstormed arguments

Decide who will speak

Plan basic strategy

0:10-0:30 - Run the Debate

Use the simplified format above

Teacher acts as timekeeper

Don’t interrupt for coaching—let it unfold naturally

0:30:40 - Whole Class Debrief (This is the most important part!)

Teacher leads discussion:

“Okay, that was Debate Zero. Let’s talk about what we learned.

For Speakers: What was hardest about giving your speech? What would you do differently next time? [Students will say: “I forgot my arguments,” “I didn’t know what to say when they asked questions,” “I ran out of time,” “I talked too fast”]

For Cross-Examiners: What was your goal when asking questions? Did you achieve it? [Students will say: “I wanted to prove they were wrong,” “I tried to get them to admit something,” “I didn’t know what to ask”]

For Judges: How did you decide who won? What made one side’s arguments stronger? [Students will say: “They had better examples,” “They answered the other side’s points,” “They seemed more confident”]

Now here’s what I noticed:

[Point out specific effective moments: “When Sarah asked about implementation costs, that was a strategic question”]

[Point out missed opportunities: “The Negative never responded to the Affirmative’s fairness argument—in debate, if you don’t answer, you lose that point”]

[Normalize nervousness: “I saw some of you were nervous. That’s completely normal. By our sixth debate, you won’t be.”]

The good news: You now know what debate feels like. Next time, we’ll add structure—rubrics, evidence requirements, research time. But the basic format is what you just experienced.

The better news: This doesn’t count for a grade. You got to make mistakes and learn from them. That’s the whole point of Debate Zero.”

Homework: Write a reflection on the debate

Grading Debate Zero: Extra Credit for Completion

Debate Zero should not be graded on quality. Instead:

Extra Credit Option 1: Participation Points

5 points extra credit for participating in any role

No rubric evaluation

Completion-based only

Extra Credit Option 2: Reflection Assignment

Participate in Debate Zero (required, no points)

Write 1-page reflection for 10 points extra credit:

What role did you have?

What was hardest about it?

What did you learn about debate that surprised you?

What will you do differently in Debate 1?

Which role do you want to try first in a graded debate and why?

Why extra credit?

Makes it optional for students who are terrified (they can watch and learn)

Rewards students who try despite nervousness

Creates positive association with debate before grades enter the picture

Gives struggling students a low-risk way to boost their grade

What Students Learn from Debate Zero

Even in a 30-minute practice round, students discover:

Speaking is survivable. “I was nervous but I did it and didn’t die.”

Preparation matters. “I wish I’d organized my points better before starting.”

The other side has good arguments too. “I didn’t think about their perspective until they said it.”

Judges decide, not personal opinion. “I personally agreed with the Negative, but the Affirmative won because they had better evidence.”

You can learn by watching. Students who observe see what works and what doesn’t.

Losing isn’t shameful. “Our team lost but we learned what to improve.”

This is actually kind of fun. Once the fear subsides, many students enjoy the intellectual challenge.

Common Debate Zero Disasters (And Why They’re Good)

Disaster 1: Speaker freezes and can’t think of anything to say

Why it’s good: Better to freeze in practice than in graded debate

Debrief lesson: “This is why we prepare written outlines next time”

Disaster 2: Cross-examination becomes argument instead of questions

Why it’s good: Students learn the difference between questioning and debating

Debrief lesson: “Cross-ex is for asking questions, not making speeches. Save your arguments for your speech time.”

Disaster 3: Judges all vote based on personal opinion, ignoring arguments

Why it’s good: Reveals the need for judging training and frameworks

Debrief lesson: “Judges have to set aside personal views and evaluate arguments. In Debate 1, we’ll use judging rubrics to help with this.”

Disaster 4: Team has no strategy, just individuals talking

Why it’s good: Shows why team preparation matters

Debrief lesson: “Notice how the team that coordinated their arguments did better than the team where everyone said random things?”

Disaster 5: Students cite made-up “facts”

Why it’s good: Highlights the need for real evidence

Debrief lesson: “In real debates, we verify sources. Making up evidence is academic dishonesty.”

After Debate Zero: Building Toward Debate 1

What changes in Debate 1:

Tell students after Debate Zero:

“Now you know what debate feels like. In Debate 1, we’re adding:

Research time: You’ll have two days to find real historical evidence

Evidence cards: You’ll document your sources properly

Rubric grading: You’ll know exactly what’s expected for each role

Preparation time: Teams will have structured time to plan strategy

Written decisions: Judges will explain their reasoning in writing

Debate Zero showed you the format. Debate 1 will teach you the skills. By Debate 3, this will feel natural.”

Variations on Debate Zero

Variation 1: Fishbowl Debate

One Affirmative team vs. one Negative team debate in front of class

Rest of class observes and takes notes

Debrief focuses on what observers noticed

Good for very large classes (30+ students)

Variation 2: Multiple Simultaneous Mini-Debates

Divide class into 4-5 small groups

Each group runs their own debate on the same resolution

Teacher rotates to observe

Debrief representatives from each group share what happened

Good for getting more students active roles

Variation 3: Build the Debate Together

Stop after each speech to ask: “What would make this stronger?”

Collective coaching in real-time

More instructional, less assessment

Good for classes with no debate experience at all

The Most Important Thing About Debate Zero

Debate Zero exists to answer one question: “Can I do this?”

The answer needs to be: “Yes, and here’s proof—you just did.”

Not perfectly. Not expertly. But you did it.

That’s the confidence students need to approach Debate 1 ready to learn rather than paralyzed by fear.

Part 3: Using AI as a Debate Partner

Using AI as a Debate Partner

Teacher Introduction to Students:

“Let’s talk about AI. You have access to ChatGPT, Claude, and other AI tools. I know you’re using them. Rather than pretend you’re not, let’s talk about how to use them productively for debate.

Here’s the key principle: AI is a thinking partner, not a thinking replacement.

AI can help you generate ideas, test arguments, and organize your thoughts. What AI cannot do—and what you must do—is defend those ideas under cross-examination, evaluate evidence critically, and make strategic choices about what arguments matter most.

In fact, debate is the perfect place to use AI because debate has a built-in BS detector: if your AI-generated argument is weak, your opponent will expose it immediately. You can’t hide behind AI-written text when someone asks you tough questions.

Here are the ways you CAN and SHOULD use AI, and the ways you CANNOT.” [The “CANNOTs” are what I call suggested prohibitions, as I believe if you use AIs this way it will hurt your debate performance and will impact your debate grade.”]

1. AI as Preparation Partner

What this means: Use AI to brainstorm arguments and generate ideas during the research phase.

How to use it:

Prompt AI with: “I’m debating the resolution ‘The Industrial Revolution improved the lives of ordinary people in American cities.’ I’m on the Affirmative side. Help me brainstorm three strong arguments supporting this position.”

AI might respond with:

Economic opportunity argument (wages, employment)

Social mobility argument (class movement, immigrant opportunities)

Infrastructure development argument (reforms funded by industrial wealth)

Then YOU must:

Research whether these arguments are actually true

Find specific evidence for each argument

Decide which arguments are strongest for THIS debate

Understand the arguments well enough to defend them

Good use example: “I used AI to generate 10 possible arguments. Then I researched each one. Three had strong historical evidence, four had weak evidence, and three were actually contradicted by the sources I found. I chose the three with strong evidence to use in my speech.”

Bad use example: “AI gave me three arguments, so I put them in my speech without checking if they’re true or finding actual sources.”

Why this is allowed: Brainstorming is a legitimate use of AI. Professional researchers brainstorm with colleagues—AI is a brainstorming colleague. The key is you still have to verify, research, and understand everything before you use it.

2. AI as Research Partner

What this means: Use AI to help find sources and summarize information, but ALWAYS verify.

How to use it:

Prompt AI with: “What are credible sources about wage growth during the Industrial Revolution in the United States, 1860-1900?”

AI might respond with:

Robert Whaples’ work on labor history

Census Bureau historical statistics

Academic articles on economic history

Then YOU must:

Actually go find those sources (don’t trust that AI cited them correctly)

Read the sources yourself

Create evidence cards with proper citations

Verify that the source says what AI claims it says

CRITICAL RULE: Never cite a source that AI gave you without verifying it yourself.

Good use example: “AI suggested I look at Robert Whaples’ work on child labor. I found his 2005 EH.Net Encyclopedia article, read it, and created an evidence card with the actual quote and citation. In the debate, when asked for my source, I had the real article.”

Bad use example: “AI told me that ‘According to historian Robert Whaples, wages increased 60%.’ I used that in my speech. When asked for the source in cross-examination, I said ‘AI told me’ and couldn’t produce the actual article.”

Why this is allowed (with verification): AI can point you toward useful sources faster than random searching. But AI also hallucinates sources that don’t exist. You MUST verify every single source yourself. If you can’t find it, you can’t use it.

Teacher enforcement:

Evidence cards must include URLs

Random spot-checks: “Show me where you found this source”

If student can’t produce the actual source: evidence is struck, points deducted

3. AI as Argument Choice Partner

What this means: Use AI to help you evaluate which arguments are strongest and which to prioritize.

How to use it:

Prompt AI with: “I have three arguments for my debate: (1) wages increased 60%, (2) people chose to migrate to cities, (3) industrial wealth funded reforms. Which argument is strongest? Which is most vulnerable to counter-arguments?”

AI might respond with: “Argument 1 is strongest because it has specific data. Argument 2 is vulnerable because opponents can claim people were forced to migrate. Argument 3 depends on whether reforms came fast enough.”

Then YOU must:

Decide if you agree with AI’s analysis

Prepare responses to the vulnerabilities AI identified

Make your own strategic choice about which arguments to emphasize

Understand WHY each argument is strong or weak

Good use example: “AI said my wage argument was strongest, but when I thought about it, I realized the migration argument is actually harder for opponents to refute because I have Census data showing people chose to come. I made my own decision to lead with the migration argument.”

Bad use example: “AI said argument 1 was strongest, so I only used that one and didn’t prepare the others.”

Why this is allowed: Getting a second opinion on strategy is smart. Athletes watch game film. Lawyers consult colleagues. Using AI as a sounding board for strategic choices is good preparation. But YOU make the final decisions.

4. AI as Counter-Argument Partner

What this means: Use AI to anticipate what the other side will argue and prepare responses.

How to use it:

Prompt AI with: “I’m arguing that the Industrial Revolution improved lives. What are the three strongest arguments my opponents will make against this position?”

AI might respond with:

Working conditions were dangerous and exploitative

Living conditions in tenements were terrible

Wealth inequality increased dramatically

Then YOU must:

Prepare specific responses to each counter-argument

Find evidence that addresses these concerns

Practice defending your position against these attacks

Develop cross-examination questions that expose weaknesses in these arguments

Good use example: “AI predicted they’d argue about dangerous working conditions. I prepared three responses: (1) conditions were also dangerous on farms, (2) workers chose factories over farms anyway, (3) industrial wealth eventually funded safety reforms. When they made that argument, I was ready.”

Bad use example: “AI said they’d argue about working conditions. I didn’t prepare a response because I thought my arguments were strong enough.”

Why this is allowed: Anticipating opposition is a core debate skill. Before AI, debaters practiced with partners who played devil’s advocate. AI is a convenient devil’s advocate available 24/7. The key is you still have to develop the responses yourself.

5. AI as Citation Partner

What this means: Use AI to help format citations correctly according to academic standards.

How to use it:

Prompt AI with: “I have this source: an article by Robert Whaples called ‘Child Labor in the United States’ from EH.Net Encyclopedia published September 27, 2005. How do I cite this properly?”

AI might respond with: “Whaples, Robert. ‘Child Labor in the United States.’ EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. Economic History Association, September 27, 2005.”

Then YOU must:

Check that the formatted citation is correct

Include it on your evidence card

Keep the actual source so you can produce it if challenged

Good use example: “I had five sources and wasn’t sure how to format a government document citation. AI showed me the format. I double-checked it against our citation guide, and it was correct. I used it on my evidence card.”

Bad use example: “AI formatted my citation, so I didn’t check if it was right. Turns out AI put the date in the wrong place and I lost points for improper citation.”

Why this is allowed: Citation formatting is technical and tedious. Using AI to format citations is like using a calculator for math—it’s a tool that handles mechanical tasks so you can focus on substance. But you still need to verify it’s correct.

6. AI as Clarity Partner

What this means: Use AI to help you express arguments more clearly and identify unclear reasoning.

How to use it:

Prompt AI with: “Here’s my argument: ‘The Industrial Revolution was good because economic stuff improved and people had more opportunities for different kinds of work.’ How can I make this clearer and more specific?”

AI might respond with: “Your argument has the right idea but needs specificity. Instead of ‘economic stuff improved,’ say ‘real wages increased 60% according to economic historian Robert Whaples.’ Instead of ‘different kinds of work,’ say ‘factory jobs offered social mobility independent of land ownership, unlike agricultural work.’”

Then YOU must:

Decide if AI’s suggested revision is actually clearer

Make sure you understand the clearer version well enough to defend it

Practice delivering the clearer version so it sounds natural, not AI-written

Good use example: “My original argument was vague. AI helped me see that I needed specific data points and clearer causal links. I revised it to be more precise, and I understood why the revision was stronger.”

Bad use example: “AI rewrote my whole speech to sound more sophisticated. I delivered it, but when asked questions in cross-examination, I couldn’t explain what the big words meant.”

Why this is allowed: Getting feedback on clarity is like having a writing tutor. The goal is to make YOUR thinking clearer, not to have AI do your thinking for you.

7. AI as Speech Organization Partner

What this means: Use AI to help structure your speech logically and decide the order of arguments.

How to use it:

Prompt AI with: “I have three arguments: wages increased, people chose cities, and reforms were funded. What order should I present them in for maximum persuasive impact?”

AI might respond with: “Lead with the migration argument (people chose cities) because it’s harder to refute—you have Census data on voluntary migration. Then present the wage data to explain WHY they chose cities. End with reforms to address the ‘but conditions were terrible’ counter-argument.”

Then YOU must:

Evaluate whether this order makes strategic sense

Consider your specific opponents and what they’re likely to argue

Make your own decision about organization

Be able to explain why you chose this order

Good use example: “AI suggested leading with migration, but I decided to lead with wages because I knew my opponents had weak evidence on this point and I wanted to establish economic improvement first. I made a strategic choice based on my team’s strengths.”

Bad use example: “AI said to organize it this way, so I did, even though I didn’t understand why that order was better.”

Why this is allowed: Organization is a rhetorical skill. Getting advice on structure is like asking a teacher “Does this order make sense?” You still make the final decision.

8. AI as Cross-Examination Prep Partner

What this means: Use AI to generate potential cross-examination questions you might face or want to ask.

How to use it:

Prompt AI with: “My opponent will argue that working conditions were terrible. What questions should I ask in cross-examination to undermine this argument?”

AI might respond with:

“Do you have evidence comparing factory conditions to farm conditions?”

“If conditions were so terrible, why did migration to cities continue for 40 years?”

“When you say ‘terrible,’ what specific metrics are you using to measure that?”

Then YOU must:

Decide which questions are most strategic

Anticipate how opponents might answer

Prepare follow-up questions

Practice asking questions in a way that sounds natural, not scripted

Good use example: “AI generated 10 possible questions. I chose the three that would expose gaps in their evidence. I practiced asking them out loud so I’d sound natural. During cross-ex, I used two of them effectively.”

Bad use example: “AI gave me questions, so I asked them exactly as written without thinking about what answers I might get or why these questions mattered.”

Why this is allowed: Preparing questions is part of debate prep. Before AI, you’d brainstorm with teammates. AI is another brainstorming tool. But you have to understand the strategic purpose of each question.

What AI CANNOT Do (And You Cannot Use It For)

❌ AI cannot write your speech for you.

You cannot prompt AI with “Write a 5-minute Affirmative speech arguing the Industrial Revolution improved lives” and deliver what it generates. Why not?

You won’t understand the arguments well enough to defend them

AI might fabricate sources

When cross-examined, you’ll be exposed as not knowing your own case

It’s plagiarism

The rule: AI can help you brainstorm and organize. YOU must write the speech in your own words.

❌ AI cannot replace your understanding.

If you can’t explain an argument without looking at AI’s text, you don’t understand it well enough to use it. Period.

Test: Can you explain your argument to a teammate without notes? If not, you don’t own it yet.

❌ AI cannot be your source.

You cannot say “According to AI...” or “ChatGPT says...” in a debate. AI is not a credible source. AI is a tool for finding sources, not a source itself.

The rule: Every piece of evidence must come from a real, verifiable source that you’ve actually read.

❌ AI cannot make strategic decisions for you.

AI can offer suggestions. YOU decide which arguments to make, which evidence to use, how to respond to opponents. If you’re just following AI’s advice without thinking, you’re not learning.

The rule: You must be able to explain WHY you made each strategic choice.

AI Disclosure and Ethics

Teacher’s role:

“I’m not trying to catch you using AI inappropriately. I’m trying to teach you to use it productively. If you’re unsure whether something is okay, ask me. What I care about is: (1) Do you understand your arguments? (2) Can you defend them under questioning? (3) Did you verify your sources? If yes to all three, you’re using AI correctly.”

Why Debate Makes You AI-Proof

Here’s the reality: AI can generate a pretty good essay. AI can generate a decent speech. But AI cannot:

Respond to unexpected questions in cross-examination

Adjust strategy mid-debate based on what opponents actually argued

Evaluate which judge will be persuaded by which arguments

Make split-second decisions about what to prioritize in rebuttal

Defend ideas when someone challenges them in real-time

This is why debate matters MORE in the AI era, not less.

In the future, generating text will be trivial. What will matter is:

Can you defend your ideas when challenged?

Can you think strategically under pressure?

Can you evaluate competing claims and decide which is stronger?

Can you communicate persuasively in real-time interaction?

These are debate skills. These are human skills that AI can’t replicate.

Tell students:

“The reason I’m teaching you debate is precisely because AI exists. In 10 years, AI will write your first drafts. What will make you valuable is your ability to defend those drafts, critique them, improve them, and persuade other humans that your ideas are worth implementing. Debate teaches those skills. AI is a tool you’ll use. Debate is the skill that makes you irreplaceable.”

Teacher Enforcement

How do you prevent AI misuse without banning it?

1. Design assignments that require human thinking:

Cross-examination can’t be AI-generated—it’s responsive to what opponents say

Judge decisions require evaluating specific arguments from the actual debate

Reflection papers require meta-cognition about personal growth

2. Assess understanding, not just output:

During prep time, ask students to explain their arguments without notes

“Tell me why you chose this piece of evidence over that one”

“What’s your response if opponents argue X?”

If they can’t explain, they don’t understand it well enough to use

3. Verify sources randomly:

“Show me the actual source for that statistic”

“Open that article and point to the quote you’re using”

If they can’t produce it, it doesn’t count

4. Catch plagiarism through questioning:

In cross-examination: If they can’t answer basic questions about their own evidence, it’s clear they didn’t actually understand it

This is self-correcting—students who use AI without understanding get destroyed in cross-ex and learn not to do it again

5. Normalize productive AI use: