"AI Policy" Considerations for Schools

An essential ingredient of any (generative) AI Policy is basic AI literacy training for faculty and students; otherwise, they cannot understand it and meaningfully implement it.

Stefan Bauschard is the Co-Developer of Designing Schools AI Bootcamp; Co-Founder of Educating4ai.com; Co-Editor Navigating the Impact of Generative AI Technologies on Educational Theory and Practice. He brings nearly 40 years of involvement with speech and debate programs to his work.

In this post, I review some key ideas schools should consider when developing an “AI Policy.”

TLDR

An essential ingredient of any (generative) AI Policy is basic AI literacy training for faculty and students; otherwise, they cannot understand it and meaningfully implement it.

Assumptions: Students want to use GAI and they will use it; it will be difficult to prevent them from doing so; tech change is rapid; gaps between schools are growing.

Practical: Keep it short; iteration; terminology; supported vs. allowed.

Legal: Cybersecurity; privacy; plagiarism; human-in-the-loop; discrimination; hallucination.

Ethics: Reduce the focus on student “cheating” and instead focus on the obligation to educate students for an AI world. Consider it an obligation to help them develop the knowledge and skills needed to manage the potentially terrible downsides of AI-enabled social media.

Teachers: Experimentation; age limits; knowledge; citing AI; lesson design; review of student work.

AI literacy: You can’t implement an AI policy without AI literacy; how the tools work; strengths and weaknesses; social harms,

Suggestions for moving forward: three-month, six-month, and nine-month plans

Assumptions

Schools cannot control the use of generative AI by students, but they can influence it. Unless your school has a no devices policy, I don’t see how schools can control the use of GAI in school. GAI is available at openai.com (ChatGPT), Bing.com/new, Anthropic.com/Claude, Perplexity.ai, you.com, bard.google.com (and other places in the Google suite), Pi.ai, SnapChat (which is where most teenagers use it), WhatsApp, and the Microsoft Suite (coming). Most of the above are also accessible via phone app. Students can have their own APIs that link websites or apps they’ve developed directly to OpenAI or other models (this isn’t hard to do), and there are literally thousands of other places where the essential “content” of these apps can be accessed.

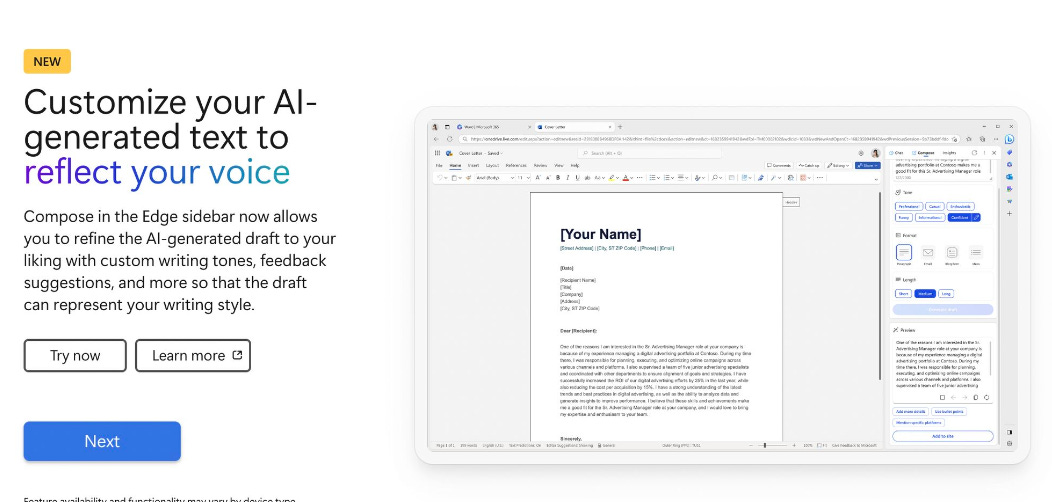

There are also specialized writing apps (Hyperwriteai.com, getconch.ai) that help students write in their own voices (ChatGPT and Anthropic also do that). And so does the new Bing Browser.

Unriddled appears to do a great job of integrating and synthesizing bibliographic references.

As noted by Kevin Roose in the New York Times August 24th: Teachers should “(a)ssume that 100 percent of their students are using ChatGPT and other generative A.I. tools on every assignment, in every subject, unless they’re being physically supervised inside a school building."

Schools can try to play whack-a-mole and restrain all of those places, but the minute students step off a school wireless network or device (including when in school), they have access to all of these sites.

There are so many that it is not practical to even monitor use. I don’t see how common suggestions to have some sort of “Generative AI Czar” in a school keep track of every GAI being used is really practical.

Of course, there is always the hope that the plagiarism detectors will catch students. We are aware that those produce a lot of false negatives and positives, and students can easily interfere with the predictability of the output, undermining the detectors. The proprietors of those systems say that, at best, a high score on a detector should produce a “conversation” with a student. There will be a lot of “conversations” this year. [Summary of problems with the detectors].

And these conversations will be interesting, because approximately 1/3 of teachers who are supposed to initiate the conversations have never used a LLLM such as ChatGPT….

Students want to learn to work with GAI. Schools are apprehensive about GAI for a variety of reasons, but students want to work with it because they know they will use it in the workforce. For this reason, they don’t necessarily consider it to be cheating; in fact, they see that by being denied it, they are being cheated out of learning to prepare for the workforce. I know of many college students who withdrew from classes this fall because their professors said, “No GAI.”

Kevin Roose, cited above, adds: “(S)tudents at many schools are racing ahead of their instructors when it comes to understanding what generative A.I. can do, if used correctly.”

Technological change is rapid. We’ve obviously seen rapid advancements since November 2022, when ChatGPT was released. Will advancements continue at this pace? It’s hard to say, and there are predictions all over the place, but AI will continue to improve, potentially surpassing humans in all domains of intelligence in 10–20 years. McKinsey says there will be more technological change in the next 10 years than in the last 100 years. Since education is, broadly speaking, in the business of developing the various domains where we find human intelligence, it will continue to have a big impact on what we do. We cannot ignore it, though large parts of education seem to be doing their best to try to ignore it.

It will also create enormous pressure on schools. Decision-making across school networks, especially large public school networks or districts, requires considerable time, leadership, and often joint decision-making. Part of that process involves arriving at detailed policies that need to be communicated and implemented. Technology is likely to race ahead of that timeline. ChatGPT5 will be out before many schools have an AI strategy that addresses the capabilities of ChatGPT4.

[Integrating AI into the curriculum is good]. I put this one in brackets because I know that not everyone believes it, and this assumption is not critical to the relevance of the policy considerations I have below. But, basically, I think it is good to include it because, in the future, I think every employee will be “AI-augmented,” and if we don’t teach our students how to be properly AI-augmented, they will not be prepared for any job. And I will impact society in ways they need to understand. But even if you don’t want to put AI in the curriculum, 1-3 and 5 (next) are true.

A gap is growing between schools. Most universities are catching up, but there is an enormous gap between private schools that have embraced teaching students about GAI and public schools that have banned “AI,” though more and more public schools are embracing teaching students with and about generative AI in spite of efforts by many large districts to keep it out of school. Students in the latter are obviously being deprived of critical skills and will not leave high school “college and career ready,” and they know that, which is why they aren’t buying into the idea of not “cheating.”

See also: Georgia School District Brings AI into K-12 Classrooms

As the gap grows between schools, it will also grow between students, and schools should consider what they can do to narrow the gap.

Assumptions 1, 2, 3, and 5 are “facts” (at least according to me).

When constructing a policy, think about which of these “facts” you agree with (and there may be others) and consider what those mean each time you write something in your policy.

Practical

These are a few practical suggestions for any AI policy.

Don’t say “AI,” especially if you’re banning it. “AI” is used in many tools, from Google search to Canva to Quizlet. Saying you are “banning AI” will instantly undermine the credibility of your policy and destroy your credibility with anyone who knows anything about the technology.

Length. At least for any publicly-facing policy and those that might apply to classroom use, you should keep the policy short (1 page). If you don't, people will simply not read it. You could also have a longer policy that is available for everyone to read if they want more information.

Iterative. The technology will change rapidly, and the policy will need to be updated, but once it’s created, there can only be essential updates. People can’t constantly read new policies and adjust on the fly. You should only send out an update if it is essential. You can update it as often as you’d like, but only re-release it when absolutely necessary.

Administrator vs. teacher Teachers need to know about any policies that govern use in the classroom. They don’t need to know about cybersecurity policies. Schools may want to have policies that govern how applications are chosen and utilized, but teachers do not need to know all the details.

Terminology. The use of AI-specific terminology should be kept to a minimum in order to make sure most individuals can understand the policy.

Supported vs. allowed There is arguably a difference between simply not blocking an application or website and (1) having teachers encourage its use and/or (2) having teachers require its use. Schools take on greater responsibility when teachers require or suggest its use.

Issues

Independent of academic criteria, there are some things that should be considered when crafting a policy.

Legal

Cybersecurity. Does any AI academic application pose a cyber security threat? How can any threat be minimized? Is it so severe that it requires a use restriction? Is the risk materially different than other apps currently allowed?

Privacy. Federal privacy law on student use is antiquated and doesn’t really account for the last 15 years of technology development. Schools must abide by the law even though they are aware that students spend the entire day on Snapchat and that Google Maps tracks their movements. Which apps can meet these antiquated legal requirements and still be useful? Is there a way to prevent antiquated laws from preventing schools from teaching effectively in an AI world?

Role of plagiarism detectors. Some universities have disabled TurnItIn’s plagiarism detector for the reasons above, and some K–12 schools are apprehensive about its use. Given the number of false positives generated by such detectors, it is important for schools to communicate to teachers that the detectors alone cannot be the basis for disciplinary action and that even the companies that produce these detectors only recommend using the result as a piece of evidence to start a conversation with a student (the ones the teachers who have never used GAI are supposed to start…). A heavy academic penalty could easily trigger a lawsuit.

Age. Some apps have age restrictions. Anthropic’s Claude, for example, is limited to those 18 years of age and older. OpenAI’s ChatGPT is limited to those 13 years of age and older, though 13–17 year olds require parent permission.

Human-in-the Loop. It should be abundantly clear in schools that people make the final decisions on all issues. AI decision-making should not override a teacher’s determination of a grade or a 503b plan. This should be clear to everyone in the school.

Waivers. Waivers are a way to limit liability (I’ll leave it to the lawyers to say how much).

Legal/Ethics/Practical

These are probably more social and practical issues, but I could see related legal issues developing.

Discrimination. GAI systems that are trained on the history of human writing (and mostly on English-language sources) tend to produce discriminatory output. That can be reduced through effective prompting, but teachers and students need to be aware of the possibility and how to account for it. Otherwise, a school-supported system that produced discriminatory output could create a liability, and this has social consequences regardless of liability.

Hallucinations. Simply put, hallucinations are factual errors that LLMs produce. If they produced something that is offensive (“Hitler was a ‘great’ leader,” perhaps because Hitler is associated with the word “great” because he had a large impact even though he was a terrible person), could schools be liable? Some hallucinations may upset parents and students, which is probably larger concern, especially since most (like the teachers and administrators) have not been told how LLMs work.

Risk vs. reward. Simply opening the door on a school day creates liability. So does allowing kids to put on helmets and slam their heads into each other on school property. Schools take liability risks because they know those risks are important to academic gains and social development. If we can allow kids to smash their heads into each other in 90+ degree heat, we can allow them to use generative AI.

Can do. GAI is here. Students are going to use it. They probably ought to learn how to use it well. General Counsels aren’t just tasked with minimizing risk; they are also tasked with making it possible for the “business” to succeed.

Process

The development of generative AI has been difficult for schools to keep up with. Some schools, mostly private international schools, started generating these policies last spring and involved all community members (students, parents, teachers, staff, and administrators).

If your institution doesn’t have a policy yet, this may not be possible, but over time, you should reach out to your community. As discussed at the beginning, it is very difficult for schools to regulate this technology, so the only way to make it work is with buy-in. Buy-in is more likely if you involve the community.

If you haven’t started, you’ll probably need to put something together quickly at the admin level.

Teachers

Based on survey results and some training I’ve done, I’d say approximately 33% of teachers will start the school year without even having used ChatGPT (let alone any other generative AI tool). Based on this, I suggest the following.

All teachers should have a school policy to use as a starting point and adapt it to their classroom’s needs. If a teacher knows nothing about GAI, they can just use the school’s policy for their classroom.

[PS: If your teachers start that school year without knowing anything about AI, that’s just not on them…..]

Teachers should state a general policy and explain their role in each assignment. If teachers allow GAI usage, they should be clear on how it is allowed for each assignment.

Teachers should be allowed to experiment with GAI. GAI usage can’t be controlled in schools, and if teachers aren’t allowed to use it, we’ll never advance pedagogy around AI. [And, like the students, teachers will use it anyhow].

Teachers have to understand different limits. There is a difference between allowing students to use GAI to complete an assignment and requiring them to use it (at least for now; it will eventually become less controversial). There are also age limits on some systems, as noted above; for example, K–12 teachers should not require students to sign up for Anthropic’s Claude. Will students inevitably do so? Of course, but teachers shouldn’t require the use of a product that requires a person to be 18 to register.

Teachers should consider AI as part of the learning process. As with any technology, there is a time to use it and not to use it. Ultimately, the goal of a school is to develop intelligence in humans, not machines; AI should be used when it facilitates the development of human intelligence and not when it undermines human inteligence.

Citing GAI. MLA, APA, and others have formalized guidelines for citing the use of GAI material in academic work. This can get complicated, as students will start using GAI in an integrated way (writing some sentences, writing sentence fragments, etc.), and GAI should never be cited for facts, but there are some guidelines for citing it if it is used.

Opportunities for dialogue There should be opportunities for dialogue among teachers, especially within departments, as how it affects English, for example, is different than how it affects biology.

The teacher's use of grading and feedback should be clarified. Will K–12 schools allow teachers to use generative AI for student feedback? If so, it should be clear that personally identifiable information cannot be included in the prompt.

Teaching methods for lesson design should be clarified. There are concerns among instructional designers that teachers will use the tools to create instructional modifications and assessments without concern for “learning science.” This makes a lot of sense, but it is worth nothing that some of this is out of necessity (assigning end-product writing assignments has become substantially more complicated), that many materials are designed without detailed attention to “learning science” now (Teachers Pay Teachers….), and that the current educational system is struggling to educate many students (NAEP pass rates are 50% at best) even though we are supposedly only learning the best '“learning science” to teach.

Of course, there are teachers who need to be especially careful. Special education teachers, for example, should not stray from “”evidence-based” practices.

Ultimately, how well AI is used in schools will come down to the teachers. Their learning and development on it will be key to its success. It’s a shame that so few have had opportunities for professional learning.

Administrators

Teacher support. Administrators should clarify what support they are offering to teachers regarding student use, and potential teacher use, of GAI in the classroom.

Disciplinary approaches. Especially if your school is relying on disciplinary approaches to prevent student use of generative AI, what approaches do you have for confirming use, what’s the process for a disciplinary action, and what are the penalties? Unlike past plagiarism issues, you cannot have anything to verify the suspected output against, so what are your standards for penalizing a student? Are you really going to go with your gut? What races and classes will those penalties disproportionately fall on? [Sir, I think there is a 68% chance you were going over the speed limit; here is your ticket].

Literacy

I don’t think you can have an AI Policy without establishing some basic AI literacy amongst faculty and students; how can they otherwise understand it?

What they need to know All living human beings who work and learn in your building need to understand generative AI. It is impacting (and will further impact) literally every aspect of education and industry from this day forward. If they don’t understand the basics, they cannot understand any policy you write, cannot implement it properly in the classroom, and can't really even have any idea if students are using it.

Without literacy, teachers will not be capable of having discussions about appropriate use in the classroom and will struggle to get buy-in when developing policies that govern classroom use.

Social harms. The non-academic risks of AI-enabled social media are enormous. SnapChat has already incorporated a bot to speak with kids. Kids will be served not only content the apps know they are interested in, but they will also start generating content on the fly to keep them hooked. Young males will start dating AI girlfriends, creating estrangement and more depression. There will be more suicides, as schools sleep at the wheel.

Obligations Schools Should Consider When Designing Policies

Obligations to students. What are your obligations to students? Do you want to help them prepare for the AI World?

Obligations to teachers. What classroom supports do your teachers need to succeed in this new world?

Obligations to parents. Should you help parents understand this technology so they can help their kids?

Obligations to the community. Does your school have an obligation to help your community understand these developments?

Action Items

I’ve covered a lot of ideas. How might you process those ideas?

Items for Immediate Action—NOW

AI Literacy

Boilerplate Generative AI Policy that teachers can adapt or use if you don’t have one

GAI guidance and direction for teachers who will be managing GAI use all year

Items for Short-Term: 1-3 Months

A plausible AI policy that considers legal obligations, cyber security needs, and financial and practical concerns related to implementation

Start working with teachers for (re)training on alternative assessment methods such as authentic learning, project-based learning, portfolios, and speech and debate. GAI can be used to enhance critical thinking, but only if assignments cannot be easily completed with GAI.

Items for Medium-Term 3-6 Months

Develop an AI strategy for Fall 2024

Items for Medium-Term 6-9 Months

Finalize an AI strategy for Fall 2024